NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE A t the time the famed Library of Alexandria burned to the ground, over 2,000 years ago, it is believed to have been the home of over half a million books and documents representing a sizeable portion of the world’s knowledge.

(I take solace in imagining that one of the precious destroyed books was a volume on how to teach animals to speak, which has kept us all from now working for our dogs.)

Two millennia later, the loss of physical books has now accelerated — not because of wayward torches, but out of a desire for simple convenience. According to a recent report by the Association of College & Research Libraries, colleges are shifting the bulk of their book purchases towards e-books and other digital documents, allowing students better remote access. According to the report, e-book purchases at academic libraries grew from 54 percent of monograph acquisitions in 2020 to 69 percent in 2021.

“In a recent survey of academic library staff, strong majorities reported that they expect e-resources acquisitions to continue increasing, special collections acquisitions to remain the same, and print acquisitions to continue declining,” the report reads.

In other words, it is another step toward a world without physical books.

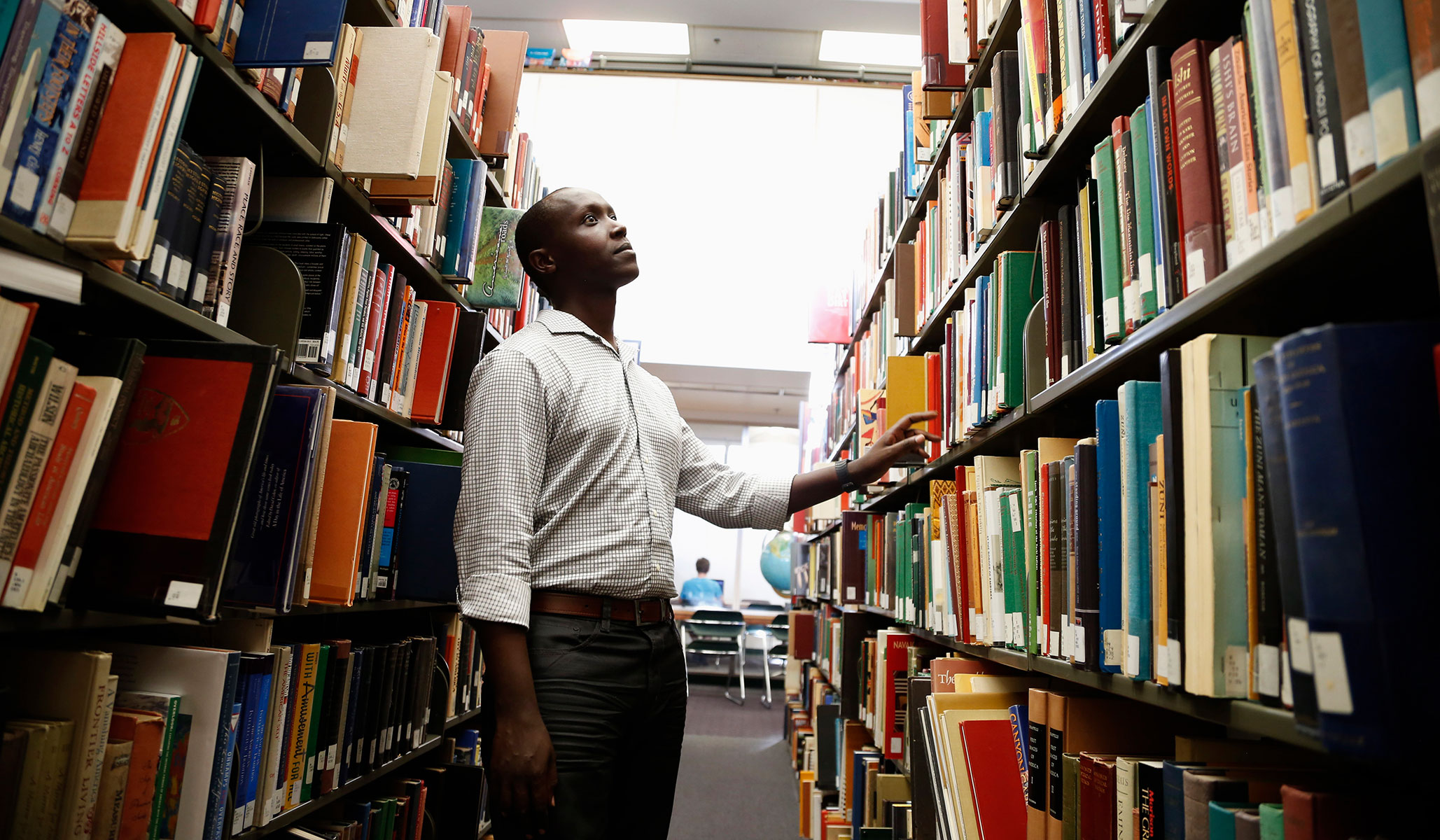

Take some time to reflect on the role of good old-fashioned printed books in our lives. They are always around us, often used solely as visual paprika to season our homes. How many of us have decided that, when on a Zoom call, there is no better way to command respect from your co-workers than to have a few books that no sane person has ever read neatly arrayed on a shelf over your shoulder.

But now that traditional physical books, and printed magazines and newspapers too, have begun to disappear in favor of the digital variety, how are you supposed to signal to your friends that you are more literate and erudite than they are? (Aside from using the word “erudite,” which, when used, signals that you are, in fact, erudite.) How are you supposed to earn the respect and admiration of America’s smartest and best-looking people if you’re at a coffee shop and they can’t see that you are reading National Review on your phone? What dinner guests are going to be intimidated when you throw a thumb drive down on the table and say, “Trust me, it contains the complete works of John Donne?”

(As I have said before, I always keep a book of poetry in my car, in hopes that if I die in a car accident the headline will read “Area Man, Lover of Yeats, Decapitated in Horrible Flaming Wreck.”)

The lack of physical books is also changing libraries themselves. Some of America’s most majestic, soaring architecture exists to house millions of pages of documents, most of which will someday be scanned in and available to anyone with a smartphone. Presumably, these books will then be boxed up and placed in the back of a warehouse, Raiders of the Lost Ark–style, never to be exhumed.

The lack of physical books is also draining our communities of retailers once dedicated to selling novels, memoirs, and cookbooks. Remember those large buildings adorned with names like “Borders” and “Barnes and Noble” and “Crown Books”? They are now known as “For Lease.”

And what is to become of the world’s ornate, cavernous buildings that housed books in the pre-digital era? Well, around a decade ago, local libraries began acquiring digital media such as DVDs and CDs to allow people to check out movies and music. Suddenly libraries went from a place where taxpayers paid to spread knowledge found in classic texts to subsidizing the truly least fortunate among us — those who had not seen The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift.

Of course, now that streaming has taken over, those DVDs and CDs may soon go the way of the printed page, collected only by hipsters who want to pretend the sound quality is much better than you find on Spotify. A few years ago, the New York City public-library system argued it was actually a First Amendment violation to bar people from watching pornography at the library.

The digital revolution has also changed what books you are likely to read. Self-publishing has flattened the publishing landscape. In the old days, book companies had the final say in what the public would see. If a publisher was willing to put time and money behind a project, then the consumer was reasonably certain it was a worthwhile, professionally produced work.

But now, in order to publish a book, one needs only an idea and an internet connection. While the old process of producing a physical book could take years, self-publishing can be done in weeks. (The author whose column you are reading now has written two self-published books, each of which has been praised by almost several people.)

Independent authors might celebrate this development, but for readers, sorting through the morass of good, mediocre, and bad books will be that much harder. (Of course, being printed by a prestigious publishing house was never a guarantee of quality. A publisher actually paid Bernie Sanders to write a book titled “It’s Okay to Be Angry About Capitalism.” The hardcover is now available online for the low price of $17.26.)

The switch to digital also changes the tactile way we interact with books and literature. Pages have been replaced by percentages (bragging that you read 100 percent of the William Manchester/Paul Reid Churchill trilogy is far less impressive than telling people you finished all 2,200 pages), and it is far less likely that you will stumble upon something unexpected and buy it, as you would while perusing the shelves at a physical bookstore. Buying a used EPUB document is just far less exciting than getting your hands on a previously owned book that might have notes or highlights indicating who owned it before you.

(Conversely, the switch to digital may please trees, which are a notoriously quiet interest group — although, as the old saying goes, if a tree reads Infinite Jest alone in a forest, everyone is going to hear about it.)

But most important, physical books provide a permanency that would go missing if everything were stored on digital files. When information is stored digitally, it is forever subject to change. If an author in the year 2023 writes a book that contains a phrase that falls out of favor 50 years from now, that phrase can always be retroactively removed if the original medium was digital. The author’s original intent will thus be erased, even if it occurs well after his death. (We have seen this even when the authors published hard-copy books, as is the case with Ian Fleming, Agatha Christie, Dr. Seuss, and P. G. Wodehouse.)

This digital bowdlerization will forever make the record of the events we are currently navigating negotiable. People reading novels or memoirs or collections of political reportage decades from now will never know if they are an accurate account of what our lives were like today, as they can always be retroactively edited to fit contemporary sensibilities.

The printed page provides permanence, stability, and consistency. When that goes away, our historical foundation will become further unmoored from reality, forcing us to rely on unreliable narratives of both our past and present. Once books become relics, the unintended consequences could be severe.

So if you’re one of those weirdos who wander through bookstores, risking permanent neck damage by cranking your head to the side to read rows of book spines, here’s to you. As Flannery O’Connor once wrote, “Push back against the age as hard as it pushes against you” — the type of wisdom one can find only in an old book.