This article is adapted from remarks Judge Duncan gave to the University of Notre Dame’s Center for Citizenship and Constitutional Government, co-sponsored by the Federalist Society.

NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE I t’s so good to be with you today. As a Catholic, I’m honored to be speaking at a university specially dedicated to Our Lady. I’m grateful to Professor Phillip Muñoz and the Notre Dame Center for Citizenship and Constitutional Government for inviting me and to the Federalist Society for co-sponsoring my visit.

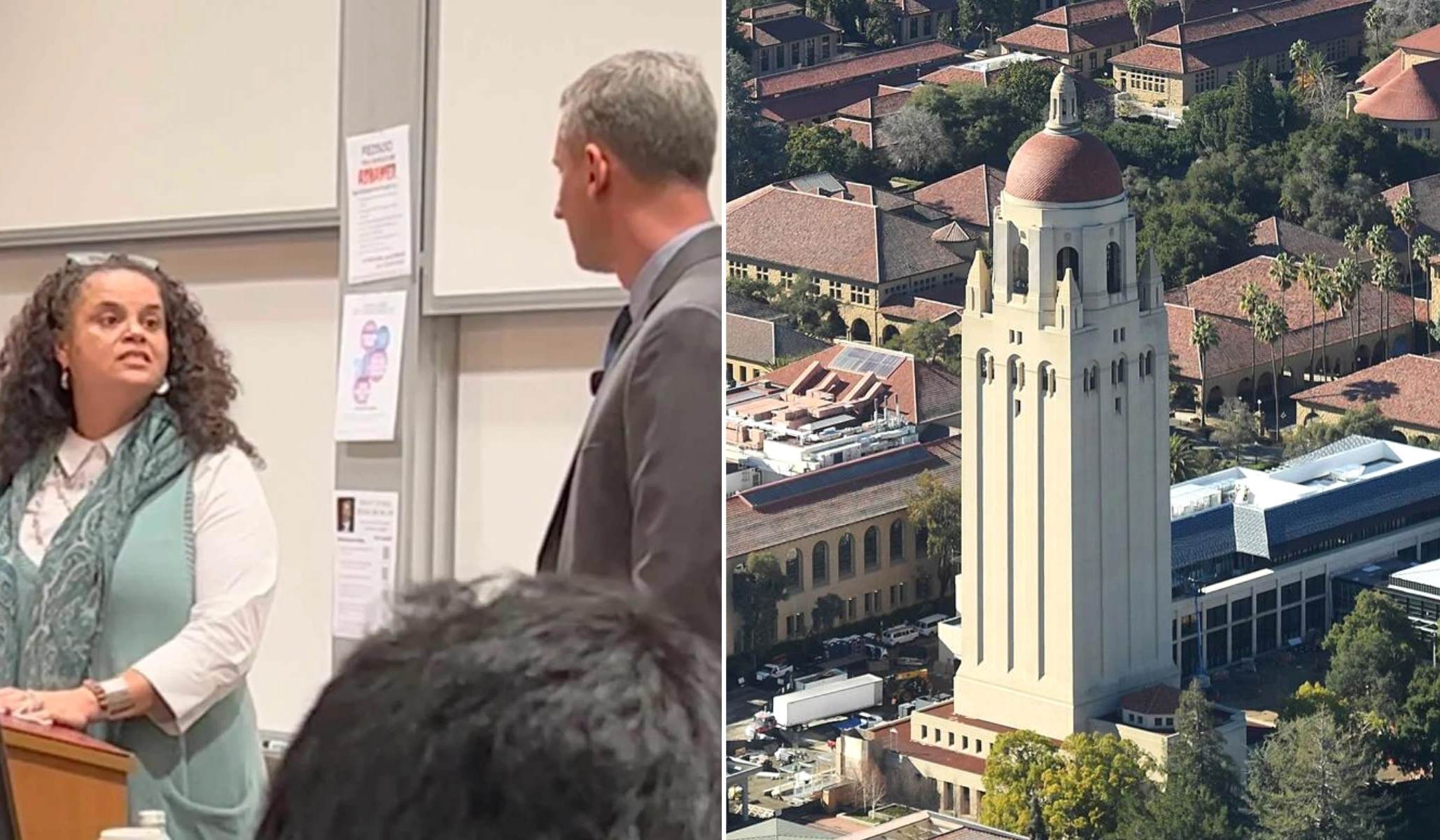

I’ve given plenty of talks at law schools over the years, but never one quite like this. This is a talk about another talk. A couple of weeks ago, on March 9, I was invited by the Stanford Federalist Society to deliver a lecture at Stanford Law School, but it was cut short by a student protest. Soon after, Professor Muñoz graciously reached out and offered me a chance to give some reflections on what happened. I gladly accepted, even though I don’t particularly enjoy talking about myself. By and large, federal judges are a reclusive bunch, and we usually talk through our opinions or about our opinions. But this is an unusual event, and it involves me — although heaven knows I wish it didn’t — and so here I am. I hope you can get something out of it.

I want to reflect on the event at Stanford from three related angles: free speech, legal education, and how we govern ourselves in this country. While I was preparing these remarks, something else remarkable happened: Just last Wednesday, March 22, the Stanford Law School dean, Jenny Martínez, sent an extraordinary letter to the Stanford community. It’s a powerful letter and a credit to Dean Martínez. The letter happens to touch on, in an eloquent way, some of the same themes I’m talking about today. So, I’ll highlight parts of the dean’s letter in my remarks. I will say at the outset that I believe the letter provides a solid basis for improving the intellectual climate at Stanford — and perhaps at other law schools — assuming its powerful words are backed up by concrete actions.

I prefer not to recount the details of what happened on March 9. I’ve done that elsewhere, and you can read that, or if you want, watch the video or listen to the audio. Suffice it to say that it was a disgrace. I truly hope what happened on that day does not reflect the cast of mind of most of the students, faculty, or administration at Stanford or at any other law school. And yet Stanford is one of the elites, so I think it’s fair to reflect on the event in a larger way — at the very least to underscore what went wrong and what we all hope will not happen again.

So, what about free speech? We have a vital tradition of free speech in this country, both in our law and our culture. That of course extends to student protests. Think of the students who refused to pledge allegiance in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnett or the Vietnam protesters in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District. The students at Stanford enjoy the same right to protest me. They can protest me every day of the week and twice on Sunday. It’s a great country where you can harshly criticize federal judges and nothing bad will happen to you. You might even get praised or promoted. The students at Stanford and other elite law schools swim in an ocean of free speech. Has any group of people ever been so free to speak in the history of our nation or any nation? Has any group ever been so privileged? In the aftermath of the event, a large number of students even protested the dean herself in her own class for the offense of apologizing to the likes of me.

But make no mistake. What went on in that classroom on March 9 had nothing to do with our proud American tradition of free speech. It was a parody of it. I’m relieved that Dean Martínez’s letter forcefully recognizes this. As she writes: “Freedom of speech does not protect a right to shout down others so they cannot be heard.” It is not free speech to silence others because you hate them. It is not free speech to jeer and heckle a speaker who’s been invited to your school so that he can’t deliver a talk. It is not free speech to form a mob and hurl vile taunts and threats that aren’t worthy of being written on the wall of a public toilet. It’s not free speech to pretend to be “harmed” by words or ideas you disagree with, and then to use that feigned “harm” as a license to deny a speaker the most rudimentary forms of civility.

Some of the students were apparently convinced that what they were doing was “counter-speech.” Wrong. Counter-speech means offering a reasoned response to an argument. It doesn’t mean screaming, “Shut up, you scum, we hate you” at a distance of twelve feet. Other students claimed this was nothing more than the “marketplace of ideas” in action. Again, wrong. The marketplace of ideas describes a free and fair competition among opposing arguments with the most compelling one, we hope, emerging on top. What transpired at Stanford was no marketplace. It was more like a flash mob on a shoplifting spree.

One final note on free speech: Do not think for a moment that the mob showed up to “respond” to my talk or engage in some high-minded back-and-forth about what I was invited to Stanford to talk about. That would have been fine. But the mob had no interest in my talk at all. They were there to heckle and jeer and shame. If you doubt that, just listen to what they said. At one point, the ringleader — a young woman clearly visible in the video — asked the crowd to “tone down the heckling slightly so we can get to the Q&A.” That’s right: Let’s have the optimal level of heckling so we can get to the good part where we hurl questions at the judge like, “How do you feel about all the people your opinions have killed?”

Let’s say the quiet part out loud: The mob came to target me because they hate my work and my ideas. They hate the clients I represented in court. They hate the arguments I made. They evidently hate my judicial opinions, although the protesters were evidently familiar with only one of the hundreds I’ve written — an opinion where I refused to enlist the federal judiciary in the project of controlling what pronouns people use. So, the protesters did not come to respond to my talk or engage in counter-speech. They just wanted to vent their rage against me. None of this spectacle — this obviously staged public shaming — had the slightest thing to do with “free speech.” It had everything to do with intimidation. And to be clear, not intimidating me, but the protesters’ fellow students. The message could not have been clearer: Woe to you if you represent the kind of clients that Judge Duncan represented, or take the same views that he has.

So, next, let’s talk about legal education. We shouldn’t forget that this incident did not occur in a campus bar at 12:45 a.m. after the USC game. It occurred in a law school — indeed, one of our nation’s elite law schools. Dean Martínez’s letter eloquently explained why this makes the incident doubly shameful.

Start with the fact that Stanford is a university. As the dean explains, “a university must sustain an extraordinary environment of freedom of inquiry and maintain an independence from political fashions, passions, and pressures.” Why? Because of the university’s mission, which, she writes, is “the discovery, improvement, and dissemination of knowledge.” This search for knowledge, for truth, can “challenge social values,” it can “create discontent with existing social arrangements,” and it can sometimes be “like Socrates, upsetting.” The antithesis of this open, curious, challenging search for knowledge is, the dean writes, “an echo chamber.” All of this is true, and it’s admirable for the dean to say it so plainly. Yet what greeted me in that classroom on March 9 was, in fact, the “echo chamber” the dean warns us about. What was most obvious was that the students were so threatened by the mere presence of someone whose views may challenge their own orthodoxy that their only response was to cover their ears by jeering and yelling.

Now add to all this one more thing: This was not only a university but a law school. As Dean Martínez explains, the students there are being trained “to make arguments on behalf of clients whose very lives may depend on their professional skill.” They must therefore learn to “confront injustice or views they don’t agree with and respond as attorneys.” That is all exactly right but, unfortunately, the temperament and cast of mind necessary to function as lawyers was not in evidence that day.

I remember when I was in law school, not a school as exalted as Stanford. From the very first day, I was keenly aware of all that I did not know, that even my very patterns of thought needed to be strengthened and refined. (I was an English-lit major.) And yet what I was led to discover by my professors was that argument — calm, reasoned, persistent, and logical argument — was the key to persuasion. By contrast, brute appeals to anger, passion, grievance — ad hominem attacks, histrionics — would not only fail to persuade, but would also cripple one’s credibility as an advocate. Naturally, I did not always agree with my professors. But I respected them, I listened to them, and I learned from them what it meant to be a lawyer.

I also remember being visited at the law school by at least two Supreme Court justices, Anthony Kennedy and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. It impressed me profoundly that they were willing to take time to interact with students at the Paul M. Hebert Law Center at Louisiana State University. Perhaps I disagreed with some of their opinions I had read in class. But the idea of shouting them down never remotely occurred to me. It would have been abhorrent. What shame that would have brought on me, my school, my professors, and my fellow students.

Dean Martínez is correct when she writes, “I believe we cannot function as a law school from the premise that appears to have animated the disruption of Judge Duncan’s remarks.” And what was that premise? That “speakers, texts, or ideas believed by some to be harmful inflict a new impermissible harm justifying a heckler’s veto simply because they are present on this campus.” I’ve heard someone comment recently that to be a lawyer means, by definition, to have to occupy the same room with people you seriously disagree with — and yet to have to engage in reasoned, indeed persuasive, argument with them. If that is true — and it is — then the primitive impulse to shout someone down is not a trait we should want to encourage in law schools. Just the opposite. It is a trait we should strive to help students unlearn.

Finally, we must not overlook why we train lawyers: to make our civil society function. Once again, Dean Martínez says this well: “Law is a mediating device for difference.” The discourse of law, and of lawyers, greatly affects how we order our lives together in a liberal democracy. I am no political philosopher, and Professor Muñoz would have much more to say about this than I. But one thing strikes me on this topic: The basic premise of a free and self-governing society is that we, as citizens, can reason together. This occurs not only in government but in the multitude of mediating institutions that constitute civil society. To accomplish this requires certain civic virtues — self-control, humility, tolerance, patience, moderation, courage, to name a few. What would happen if the cast of mind modeled in that classroom at Stanford becomes the norm in legislatures, in courts, in universities, in boardrooms, in businesses, in churches? We must resist this at all costs, otherwise we will cease to have a rule of law. Lawyers and the schools that educate them have immense responsibilities. So I am cautiously encouraged that Stanford has promised to implement some form of training for students in the virtues of civil discourse. I hope it is only the beginning.

In closing, I would like to do something that I haven’t had the chance to do since the March 9 event — and that is publicly thank the Stanford Federalist Society for inviting me to speak. Even though the talk didn’t go as planned, I owe each of you a debt of gratitude. As I was trying to say that day, I know that you would never treat your fellow students as you were treated — no matter how much you may disagree with them or with speakers they might invite to campus. I was encouraged to read this in Dean Martínez’s letter: “The Federalist Society has the same rights of free association that other student organizations at the law school have.” I encourage you to take the dean at her word. Consider also these words from her letter: “We support diversity, equity, and inclusion when we encourage people in our community to reconsider their own assumptions and potential biases.” I submit that students like you, who may find themselves out of the mainstream in certain quarters, have an important role to play in challenging your fellow students and professors to reconsider their own assumptions and potential biases on a whole range of supposed orthodoxies. There will always be people who want to tell you what to think, what to say, even what words you are allowed to use. But you are free to challenge the echo chamber with a firm “I respectfully disagree.” Do not be afraid to do that.

I am grateful for being able to speak to you today. Thank you.