NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE T hroughout my entire life as a black taxpayer I’ve heard about redlining — a practice generally, if colloquially, defined as making home loans harder to get for African Americans in black neighborhoods. Redlining is why my family didn’t have as much wealth as those of several Caucasian high-school buddies, a Reilly family friend and “calabash uncle” once told me. A two-minute search on Google (for “redlining stole black wealth”) turns up the same sort of opinions from far more reputable, or at least more mainstream, sources.

The lead result, from CBS News, is titled “What Is Redlining and Why Is It Still Happening (Across the U.S.)?” The Washington Post, in an article that prints out to several pages of single-spaced text, went with “Redlining Robs Black Families of Generational Wealth.” The New York Times brings the hammer down even more bluntly: “A vast wealth gap, driven by segregation, redlining, evictions and exclusion, separates black and white America.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, the left-slanting website Inequality.org called the practice nothing less than “Black land theft,” almost entirely responsible for the “racial wealth divide” of today. And so forth: The story line is clear as glass.

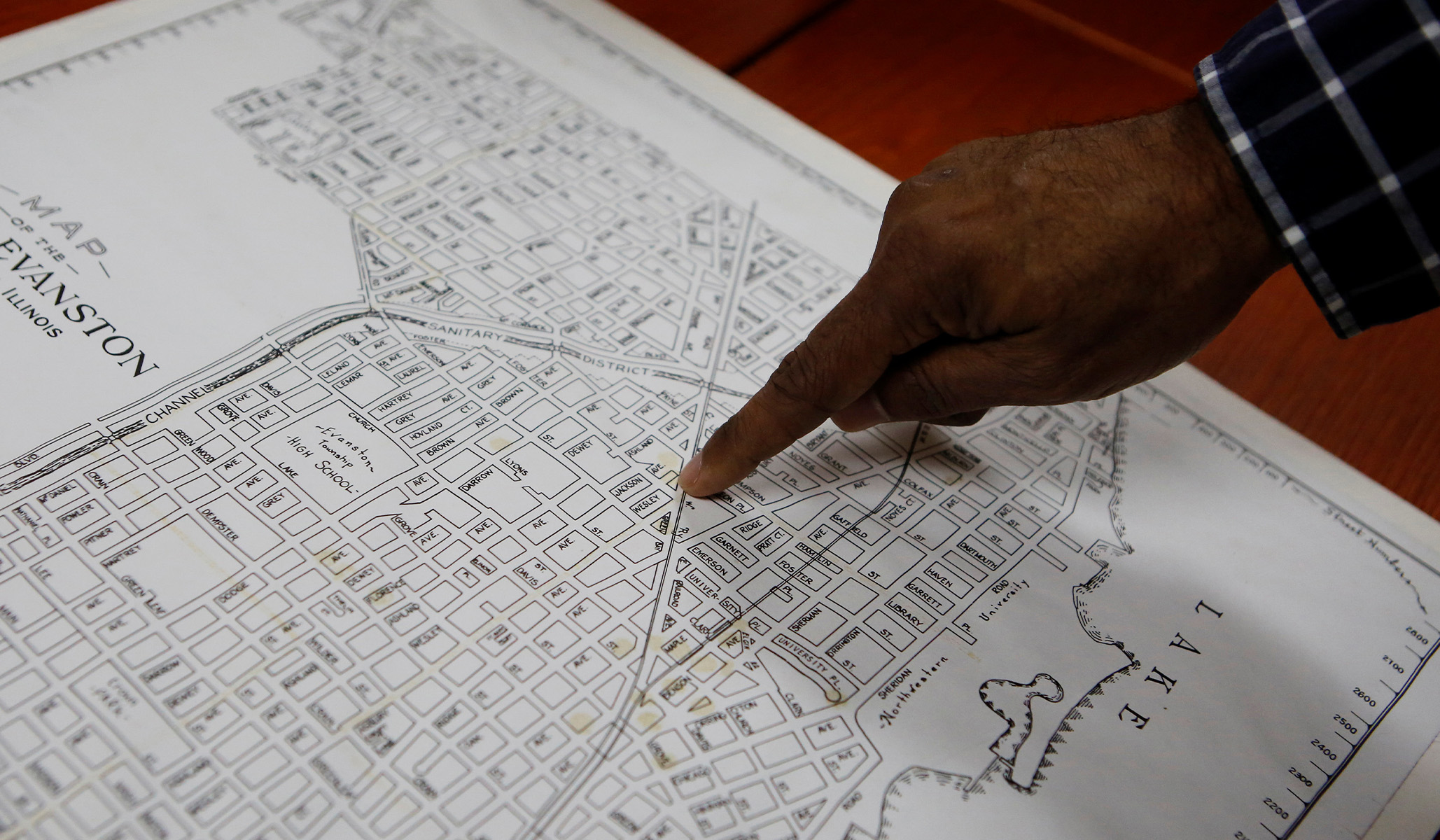

Imagine my surprise, then, when a recent academic deep dive turned up a reality very different from the Accepted Narrative. As my friend and spiritual big brother John McWhorter put it in a well-written empirical piece: “As with so many matters of race, the redlining story is more complex than many know.” According to McWhorter’s primary source, a paper by economist Price V. Fishback and his small team, “White households accounted for 82% of individuals” who lived in the risky areas that were redlined across ten major and fairly typical U.S. cities in 1930.

Further, Caucasians — almost certainly mostly members of then-abused ethnic populations such as the Irish and Italian Americans — were the sole owners of 92 percent of the homes in these slum areas. It is true that proportionately more black folks, more than 90 percent of individuals in the local black populations, owned homes in the redlined neighborhoods of the cities that were studied. However, in the context of a largely northern sample of urban locales, this seems to have been due more to plain poverty than to racism.

As McWhorter puts it: “The Redlining 101 story — that cigar-chomping bigots in suspenders drew lines around where Black people happened to live while giving loans to poor whites” is essentially just false. It also seems worth noting here that redlining was made illegal by federal law back in 1968. The practice frankly has almost nothing to do with contemporary patterns of settlement in many of the largest and fastest-growing American cities — such as Phoenix, which sprinted from 581,572 to 1,644,409 residents between 1970 and 2020, Dallas (844,401 to 1,304,379), or San Diego (696,769 to 1,386,932).

Any serious review of history will turn up similar surprises. For instance, young Emmett Till was murdered as foully as is generally assumed, but two of his four killers may have been black. Sometimes, the surprises are earth-shattering: In 1995, the legendary-in-my-field Venona cables revealed that most of the individuals famously described as having been falsely accused of espionage during the so-called Red Scare were in fact Russian spies. The list of those now implicated as certain or probable Russki agents by decrypted Kremlin messaging includes “Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Alger Hiss, Harry Dexter White, Lauchlin Currie . . . and Maurice Halperin” — and 343 other Americans.

More broadly, as I (plug incoming) point out in my upcoming book, Lies My Liberal Teacher Told Me, most social movements associated with what many now think of as “the heroic Sixties” turned out to be complete disasters, which is now thought a bit rude to discuss honestly. A short, offhand list of these failures might include: the embrace of drug culture, the extremes of the sexual revolution and the latter waves of feminism, pay-per-child welfare, mental-patient deinstitutionalization (“The Grate Society”), community policing, and pleasure-based sex education. I welcome additional suggestions!

While simple ignorance of history — an American weakness — no doubt explains some of today’s disconnect between Narrative and reality, it is hard not to notice that much of academia and the contemporary national media is dominated by partisan left-wing activists. The curation of information about what did and did not happen — and what did and did not work — in the past is very often intentional.

Interesting, no doubt: But why is all of this relevant now? Simply put, because a constant challenge posed to conservatives, and often to plain normal citizens, during today’s endless debates about topics such as “gender identity” is: “Do you want to be on the WRONG SIDE OF HISTORY?!!!” Obviously, the assumption underlying a dart like that one is that the Anointed opponents of us dirty-handed hoi polloi — the aggressively empathic upper-middle-class Left — were on the right side of history in the past . . . and will be again.

But they weren’t. Very, very often, this simply was not the case. The Tuskegee Experiment was largely administered by a famous center-left black college (while on the subject of inaccurate historical narratives), and, in the examples given above, virtually every obvious negative prediction made by critics came true.

In many contexts today, such as in the invitation of male “trans women” into women’s spaces, the primary downstream risks seem equally predictable. This is because they are. Quite obviously, most male rapists would prefer to go to a women’s prison than enter the men’s estate, and some already have in the U.S. and U.K. Letting them do so is as insane as it sounds to you.

While we try to revisit the stories of the past, it remains a damn good idea to use common sense, rather than “hope” or blind trust, as our guiding star toward the future.