NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE I t is an impossible coincidence that the people endorsing retroactive edits to the works of P. G. Wodehouse are the very types of thickheaded dilettantes Wodehouse spent most of his 90 years lampooning.

This cabal of history vandals, known in our time as “sensitivity readers,” bears a strong resemblance to the clueless elites of Wodehouse’s novels. Certain of their own genius, they bumbled their way through their era, projecting, as the literary critic Edward Galligan once wrote, “a fresh image of benign idiocy.”

But the modern-day desecration of the works of Wodehouse and other 20th-century writers is not benign. It is the erasure of history — often unpleasant, to be sure — that further rots the foundation of literature. At some point, future writers will not know where to go because they will have no record of where previous authors have been.

(That Wodehouse would be the next target was also so predictable, NR’s Charles C. W. Cooke actually predicted it.)

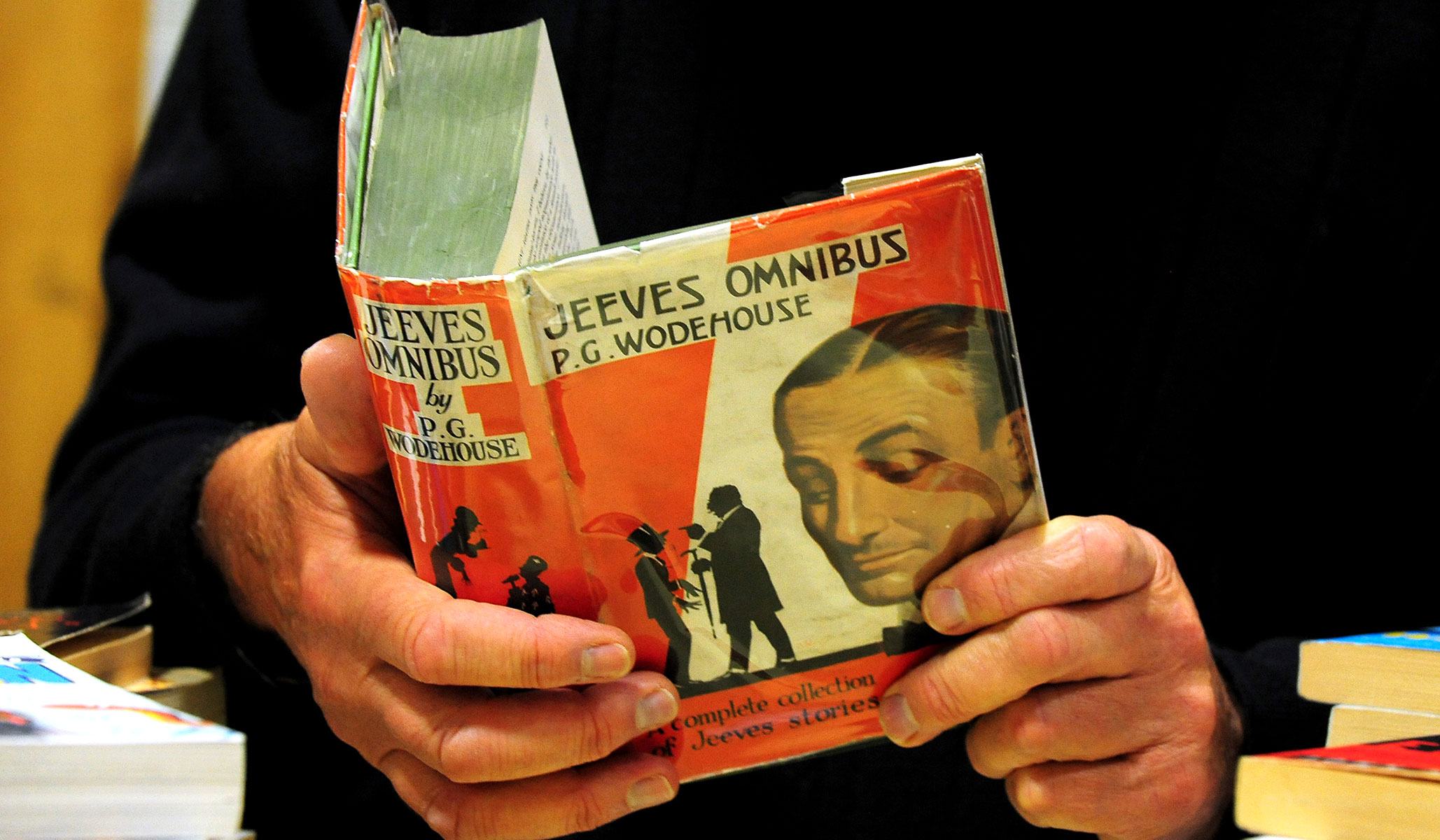

The author of the series of novels about Bertie Wooster, bumbling aristocrat, and his clever and indispensable valet, Jeeves, has now joined writers such as Roald Dahl, Agatha Christie, and Ian Fleming in having their works bowdlerized by sensitivity readers, who argue that the novels need “updating” to appeal to the tastes of modern readers.

But the idea that Wodehouse — deemed by Stephen Fry, who played the valet in the British series Jeeves and Wooster, “the finest and funniest writer the past century ever knew” — is somehow dangerous to young 21st-century readers is farcical. Wodehouse’s books are the lightest touch in literature. Once you finish reading one, you can barely remember the details of the tightly wound plot. It all just vanishes in the ether — the joy is in reading the book while you have it in your hand, not in analyzing it for anachronisms.

Nonetheless, Penguin Random House has prefaced several 2023 editions of Wodehouse’s books with trigger warnings and notices that the company has removed language it has deemed “unacceptable.”

“Please be aware that this book was published in the 1930s and contains language, themes and characterisations which you may find outdated,” the notice reads. “In the present edition we have sought to edit, minimally, words that we regard as unacceptable to present-day readers.”

In altering Wodehouse’s work, they have sprayed graffiti on what is perhaps the most acceptable language of the 20th century.

Of course, no one would deny that in Wodehouse’s over 90 works one can find bits that make decent people cringe today. Of particular interest to today’s censors is the 1934 book Thank You, Jeeves, in which the description of a blackface minstrel group performing music on a yacht incorporates the N-word seven times. (In an attempt to escape the boat, Bertie Wooster applies black shoe polish to his face to appear to be a member of the group, which is disembarking.)

For modern eyes, the word is difficult to read. But those eyes are presumably accompanied by a brain that can process the fact that the book was released in 1934, and that context is everything when judging its use. A search of a newspaper database finds well over 13,000 uses of the word in American publications that year, although its use was routinely condemned in some northern papers. The number had dropped to 2,700 by 2000 and to 73 by 2020.

But the entire essence of the book — and most of Wodehouse’s other works — is that the characters are solipsistic dunces. They incorrectly use trendy language, misstate common literary passages, and generally behave in a boorish manner. Jeeves, the most cultured character (that he is a servant is no doubt Wodehouse’s commentary on class status in Edwardian England), refuses to use the offending word, opting instead for “negroid.”

At this point, editors have a choice: They can preserve the book as it is, perhaps with a note providing context, or they can take the coward’s way out and alter the book for modern sensibilities.

That is, until “modern sensibilities” deem even more parts of the book unacceptable, leading to its outright discontinuation. Or until “modern sensibilities” demand that any book that makes certain people feel bad — today, the woke; tomorrow, some other group with different obsessions — be pulled from high-school shelves. Only someone as thick as a Wodehouse character would be unable to see where this is all going.

Nonetheless, by removing the offending passages, the sensitivity industry is convinced it is preventing these books from inflicting actual harm on others.

“It’s a craft issue; it’s not about censorship,” sensitivity reader Dhonielle Clayton told the New York Times back in 2017. “We have a lot of people writing cross-culturally, and a lot of people have done it poorly and done damage.”

Damage.

But a half decade ago, sensitivity readers were primarily used to prevent new books from riling those harboring racial and gender grievances. Evidently unsatisfied with being limited to censoring books before they came out, they have decided to reach their hand into the graves of celebrated authors of the past.

(If a sensitivity reader ever decided to remove all the offensive words from the works of Flannery O’Connor, most of her short stories about the Jim Crow South would probably fit into a tweet.)

To be sure, “avoiding damage” is woke-speak for “we are providing the reader with an inferior product and telling them it is good for them.” This is akin to concert venues adding a “convenience fee” to the cost of their tickets. Convenient for whom?

And of course, it is not simply the bright-line passages that clearly offend modern sensibilities that are being felled by the grievance artillery. In Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Augustus Gloop went from being “enormously fat” to “enormous,” which is not the same thing. In a passage in Matilda, Rudyard Kipling is unpersoned and replaced by Jane Austen. (No longer is the title character allowed to be transported to India by reading the former’s works; for some reason, imaginatively traveling to the 19th-century English estates in the latter’s novels is permissible.) In The Witches, women described as being employed as letter writers for businessmen or as supermarket cashiers are given promotions, now working as “top scientists” or business owners in their own right.

Who decided these passages were “unacceptable”? The student council at Amherst College?

Nonetheless, it is with the unassailable confidence of a squirrel darting around a dog park that these young editors have found it appropriate to retrofit history to their needs. Of course, actually making history — a process to which young people are entitled — is much more difficult than altering it. Rather than publishing works of modern value, they are content to aspire to what Alexander Pope called the “eternal sunshine of the spotless mind” — a reimagining of history with all the uncomfortable bits removed. But literature is not literature without those bits.

Wodehouse spent three-quarters of a century producing what Christopher Hitchens called “the gold standard of English wit.” What are the credentials of modern editors who now alter his prose? Simply that reading some words makes them sad.

In a literary court, it is clear who should be adjudicated the victor. (Predictably, victory for Wodehouse may come in the form of a new surge in book sales — of the untouched originals.)

The true irony in all this is that Wodehouse’s books are legendarily inoffensive. The stakes are always impossibly low, with full novels hinging on a popped hot-water bottle or a stolen constable’s cap or a missing silver-cow creamer. Nobody ever gets hurt, and everything is resolved neatly. As biographer Robert McCrum noted, each Wodehouse novel employs the same common themes: “A young man hopelessly in love with an unsuitable girl; characters with shady secrets; comic crooks leading double lives; and a stolen pig.”

To his credit, Wodehouse knew this day would one day come.

“Humorists have been scared out of the business by the touchiness now prevailing in every section of the community,” he wrote in his 1956 autobiography, Over Seventy. “Wherever you look, on every shoulder there is a chip, in every eye a cold glitter warning you, if you know what is good for you, not to start anything.”

Fortunately for his fans (many of whom are as insufferable as the editors now trying to edit him), Wodehouse was not scared out of the business. But the one thing the world keeps making is more past, which provides linguistic busybodies an eternal petard with which to hoist themselves.

The punishment the aforementioned literary court should mete out to the theatrically aggrieved? They should be denied perhaps the greatest pleasure of all: Reading Wodehouse’s works, in full, as the master intended.