NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE I have lived in Colorado for over 25 years. For some time, my wife and I have considered purchasing a rental property as a retirement investment. And when considering where to buy, Colorado has always been an attractive option. The state has a tight housing market, high rents, and a landscape that draws people from all over the country.

Unfortunately, the 2022 elections vastly expanded the Democratic majorities in the state legislature, and the newly empowered progressive majority has other ideas. Chief among them is trying to repeal the state’s prohibition on local rent control, which has been in place since 1980.

The matter has become a major issue in the upcoming Denver municipal elections, and there is plenty of reason to worry. Most of the leading candidates in the field of 17 have expressed opposition to the idea, but one of the front-runners is strongly supportive, and another has repeatedly, unaccountably, refused to answer the question. My city councilwoman, for her part, has done the same, citing the fact that there’s no pending legislation before the council. However, several of her would-be colleagues — leading candidates for the at-large city-council seats — are also vocally in favor; and one is even a state house co-sponsor of the bill.

Governor Jared Polis, perhaps with an eye to presidential politics, has signaled to the state senate that he would like them to kill the bill, thus sparing him an embarrassing choice. After all, a bill to allow local rent-control laws might run afoul of his plans to centralize land-use policy.

But, for the time being, the bill is still moving through the legislative process, with the house recently agreeing to amendments that exclude nonprofit landlords and units less than 15 years old from rent controls in order to limit the damage the law might have on new development. Less thought is given, of course, to the small-property owners of modest means who are likely to buy a rental house or a condo, almost all of which are older than 15 years old.

History is also overlooked. When San Francisco first imposed rent controls, for example, it had a similar exemption. But when it eventually became clear that most of the new housing was being built by large investment groups, the city repealed the exemption. There’s every reason to believe that Colorado and Denver would follow the same path.

Whether it goes by the name of rent control or rent stabilization, the policy is roughly the same: limiting the amount by which landlords can raise rents in response to market conditions, whether in absolute terms or linked to inflation.

But regardless of how it is implemented, the fact of the matter is that rent control is a terrible idea. Its effects are almost always the exact opposite of its stated intent, and it tends to hurt most the people that it is allegedly intended to help as investors raise rent in noncontrolled units in order to recapture returns lost to rent-control measures.

The idea of 15-year exemptions on imposing rent control on new properties, as has been floated in Colorado, doesn’t offer much of an improvement. For new development, 15 years is hardly any time at all. The IRS, for example, allows depreciation of a rental property for up to 27.5 years, and Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) requires depreciation to be considered over the useful lifetime of the property, which is typically four decades. In short, a proper estimate of the return on investment almost always takes into account a period much longer than 15 years.

On top of all that, there’s plenty of evidence that rent control also manages to reduce the property values of both controlled and noncontrolled units. When Cambridge, Mass., was forced to repeal its rent control in 1994, for instance, both controlled and noncontrolled units increased considerably in value.

This is not only an additional cost to property owners, but since the mill levy stays the same, it also means lower property-tax revenue for the municipality. Ideally, that would act as a check on the size and scope of local government but, unfortunately, Denver voters over the years have shown a dismaying willingness to vote for tax increases. In the end, small-property owners will likely find themselves paying higher taxes on lower value to make up the difference.

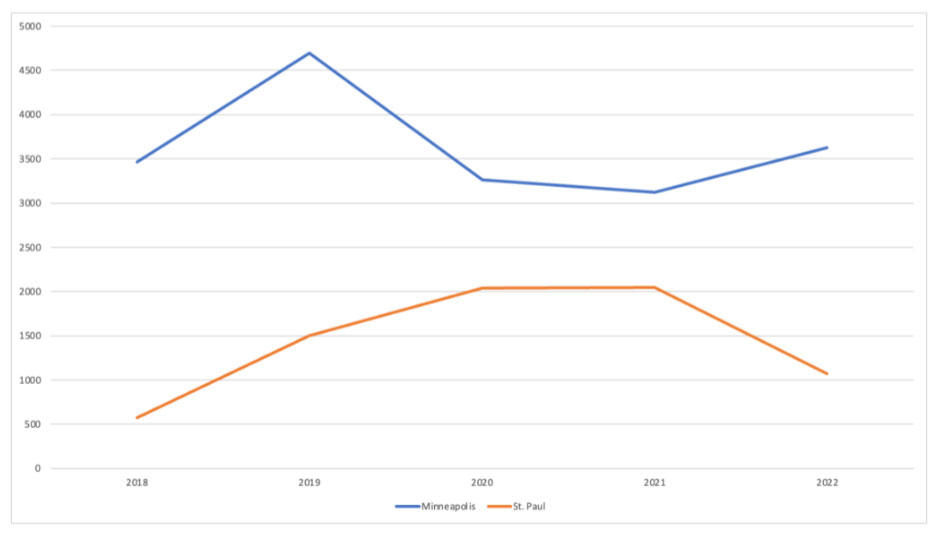

By reducing rents and returns on the landlord’s property, rent control also lessens the incentive to invest, thus degrading the available housing stock. And, once again, the data are clear. In 2021, St. Paul imposed fairly strict rent-control measures. Minneapolis did not. The results in terms of housing permits are as stark as one of those West Germany–East Germany economic comparisons from the 1980s:

If you didn’t think it could get worse than that, then think again. Rent control often fails to benefit the people who need it most. As long ago as the mid 1990s, it was understood that people will rent apartments they don’t need because it’s a good deal, and that the people doing so are frequently not the people who actually need them.

St. Paul can once again serve as an example. Even the meager benefits of its rent-control scheme are poorly distributed. Most of the benefit goes to higher-income and better-connected renters. Most of the burden falls on lower-income property owners. In sum, this means that rent control ends up being another upward transfer of wealth, all-too-typical of current progressive policies.

Colorado’s move to implement rent control may also end up chasing the tail end of a trend, as the state’s housing market is already moving to resolve some of the issues that rent control is trying to address. The Wall Street Journal reported, for instance, that rent increases are slowing down nationally as more apartments are opened. And Colorado is no longer the magnet for intrastate migration that it once was, at least in part because of the high cost of housing. Indeed, it’s almost as though there’s some invisible hand forcing things into equilibrium.

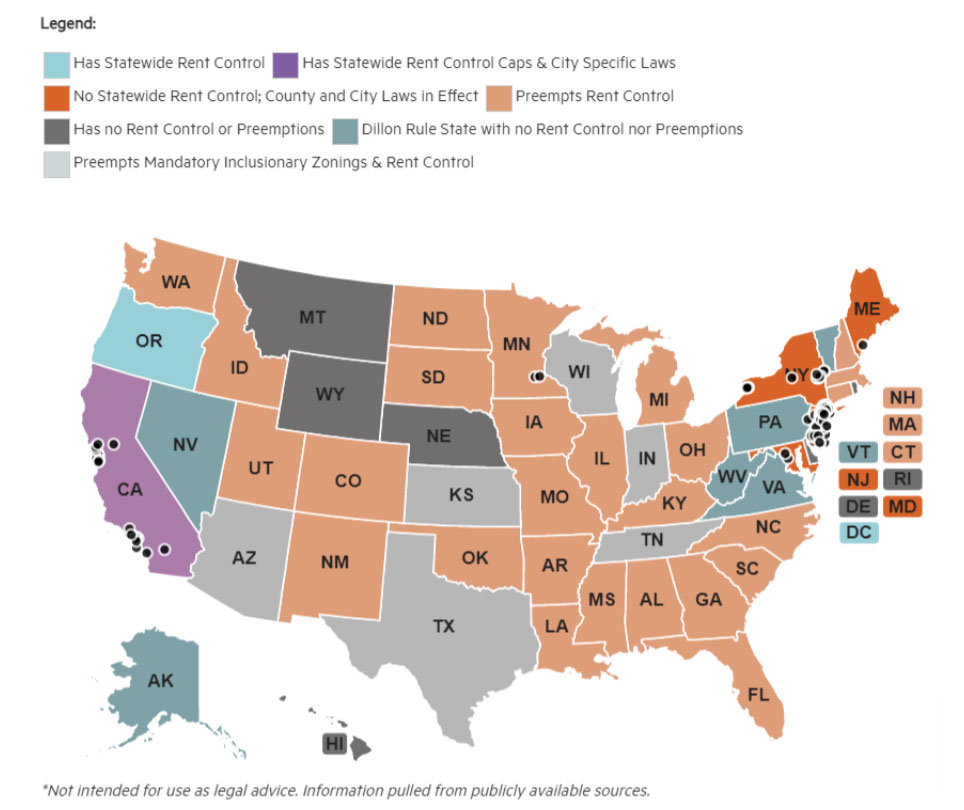

Of course, just because rent control is both a bad idea and an unnecessary one has never been a sufficient reason to stop ideologues from pushing it through anyway. And Colorado residents are rightly concerned. Should the bill pass, it would catapult the state away from the national norm to being among the most restrictive in the country.

The National Multifamily Housing Council (NMHC) keeps track of state rent-control laws. Currently, Colorado is among the 26 states that preempt rent control by municipalities. Until recently, it also preempted mandatory zoning inclusions, but it repealed that restriction so that Denver could require new development to include a certain number of so-called affordable units.

If current repeal efforts succeed in Colorado, Denver, Boulder, and some other progressive city councils would almost certainly pass rent-control laws, and the state would join Maine, New York, New Jersey, and Maryland (where there is no statewide rent control, but city and county laws are in effect). Only California and Oregon would be worse for landlords in this regard, having already implemented statewide rent control.

Colorado is not alone in looking to change its rent-control laws. No fewer than 18 states have introduced bills pertaining to rent control during their current legislative sessions. Florida’s bill seeks to revoke municipal authority to impose rent controls, which cities can currently impose for up to one year in the case of a sudden housing shortage. Montana, which has neither control nor preemption, could see a statewide preemption enacted.

The rest of the bills, however, move toward imposing state-level rent control or permitting municipal controls. Much like in Colorado, legislators in Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Mexico, Virginia, and Washington have all introduced measures that would repeal those states’ previous preemptions of local rent control. And some of those measures are likely to pass. After all, Massachusetts was only able to impose its preemption by a 51–49 referendum vote in 1994. But regardless of how many votes it gets, if the preemption is repealed, Cambridge property owners may need to brace themselves for lower property values and, probably, higher property taxes.

According to its 2023 rent-control outlook, NMHC is most worried about state action in Colorado, Washington, Nevada, and Massachusetts. In Olympia, Wash., for instance, the repeal of state preemption is just the beginning, and parallel house and senate bills limiting rent increases to between 3 and 7 percent (depending on inflation) have also seen some committee action. Although it’s true that Washington’s legislature debates rent control seemingly every session, the partisan balance has shifted in favor of the Democrats in recent years, and progressives may now see an opening that hasn’t existed for at least a decade.

Nationally, rent-control activism has taken a number of forms. In addition to state governments seeking to give the green light to municipalities to impose it, other state legislatures are considering imposing rent restrictions directly. And in Maryland and Florida, local governments seem interested in making the most of the loopholes built into their state laws.

Often lost in much of the granular policy discussions are the potential social and political effects of a national movement toward rent control.

If more and more states impose rent controls (or allow localities to do so), the result will be the gradual erosion of middle-class neighborhoods. Indeed, the reality of many of the rent-control bills that have been introduced in state legislatures is that they incentivize developers to either maximize profit on the front end, by seeking as high a rent as they can get on luxury properties for the upper class before rent controls kick in, or to minimize risk on the back end by building low-income properties that are so cheap they are unlikely to be affected by rent-control laws.

The result of rent-control legislation being discussed in state capitals today will be to limit the options of middle-class families fleeing to the suburbs, forcing people into denser developments (even outside the urban core), and ultimately setting the stage for higher suburban rents. Unfortunately, as areas become denser, they tend to vote more for Democrats. As a result, many of these disastrous policies will be self-perpetuating, and could gradually make Colorado a less attractive destination.

All that to say, my wife and I love Colorado, and we are still looking for a rental property to purchase as a long-term investment that can generate reliable income. If rent control and other anti-landlord bills pass, we might still be staying in the Centennial State, but we won’t be buying here.