Author’s note: “Weekend Short” is a weekly profile of a short story. Additional analysis by the readership is encouraged in the comments section.

Welcome to the waning hours of the weekend!

Apologies for the delay. My grandpa’s funeral occurred this past week, and it wasn’t until this afternoon that writing held any interest.

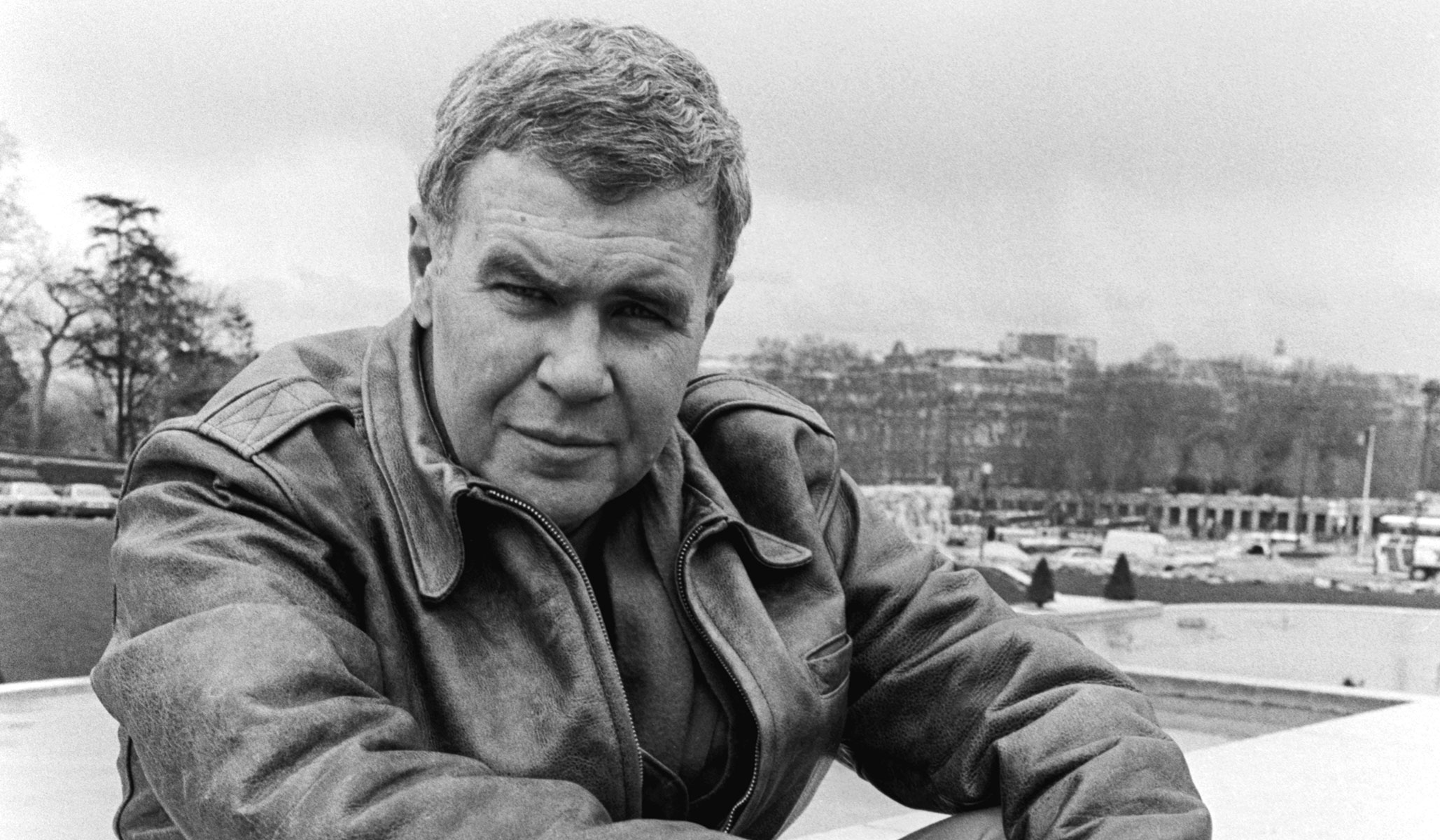

Today’s story is Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral.” Published in 1983, it is undoubtedly modern in its sensibilities — reflected in the narrator’s indolence and selfishness. The plot is simple: A blind man, for whom the narrator’s wife worked for a time and who has since corresponded with her for years, visits the married couple’s home. The narrator is uneasy, struggling with envy while harboring disgust at the blind man’s condition.

Carver writes:

This blind man, an old friend of my wife’s, he was on his way to spend the night. His wife had died. So he was visiting the dead wife’s relatives in Connecticut. He called my wife from his in-law’s. Arrangements were made. He would come by train, a five-hour trip, and my wife would meet him at the station. She hadn’t seen him since she worked for him one summer in Seattle ten years ago. But she and the blind man had kept in touch. They made tapes and mailed them back and forth. I wasn’t enthusiastic about his visit. He was no one I knew. And his being blind bothered me. My idea of blindness came from the movies. In the movies, the blind moved slowly and never laughed. Sometimes they were led by seeing-eye dogs. A blind man in my house was not something I looked forward to.

That summer in Seattle she had needed a job. She didn’t have any money. The man she was going to marry at the end of the summer was in officers’ training school. He didn’t have any money, either. But she was in love with the guy, and he was in love with her, etc. She’d seen something in the paper: HELP WANTED — Reading to Blind Man, and a telephone number. She phoned and went over, was hired on the spot. She worked with this blind man all summer. She read stuff to him, case studies, reports, that sort of thing. She helped him organize his little office in the county social-service department. They’d become good friends, my wife and the blind man. On her last day in the office, the blind man asked if he could touch her face. She agreed to this. She told me he touched his fingers to every part of her face, her nose—even her neck! She never forgot it. She even tried to write a poem about it. She was always trying to write a poem. She wrote a poem or two every year, usually after something really important had happened to her.

When we first started going out together, she showed me the poem. In the poem, she recalled his fingers and the way they had moved around over her face. In the poem, she talked about what she had felt at the time, about what went through her mind when the blind man touched her nose and lips. I can remember I didn’t think much of the poem. Of course, I didn’t tell her that. Maybe I just don’t understand poetry. I admit it’s not the first thing I reach for when I pick up something to read.

Anyway, this man who’d first enjoyed her favors, this officer-to-be, he’d been her childhood sweetheart. So okay. I’m saying that at the end of the summer she let the blind man run his hands over her face, said good-bye to him, married her childhood etc., who was now a commissioned officer, and she moved away from Seattle. But they’d keep in touch, she and the blind man.

You can read the rest here.

Assuming you’ve finished the story, let’s consider. Reading through, I realized I myself have shared the narrator’s odious view concerning the handicapped — albeit I was a kindergartner.

Eric was a classmate. He was born with a heart condition that made him weak and frail; he had thick glasses and a runny nose; he was ugly and mean. Worse, he was allowed liberties that none of the other kids were granted. I hated him. I hated how the teachers gave him unearned attention. I hated how adults in sports would go easy on him. I hated how he lorded his being six years old over us when the rest of us were five — to kindergartners, a few months of seniority is a status one cannot overcome through alternative merit. From the way he held pencils (with all five fingers) to the way his awkward gait (lurching), his presence was repugnant. I resented his existence; he was “wrong” to a five-year-old’s sensibilities.

My spitefulness was so intense that I remember opting against taking communion one night at church, because I knew I “harbored hatred in my heart” — the black mass of a child’s emotions runs far ahead of his physical stature, it must be said.

Eric died at the age of 24 after years of living in hospital rooms. I can only be ashamed at the animus I held for him when we were young. There is no lower thing than to despise those whose bodies already reject them.

When reading the narrator’s thoughts, we can see my childish prejudice lurk behind the eyes of a grown man. He’s indiscriminate, offended by his wife’s correction and former lovers; by the blind man’s touch; by his own inability to describe beautiful things. Our narrator is a degenerate materialist — drunk, stoned, and stupid. The events of the story wash over him as he stews in discontent. It takes a blind man to show him “something” — a word repeated 28 times in the story.

Carver describes the uncharity of the effortlessly whole and hale so well, it sickens the soul.

Speaking of everyone looking for something, here’s Pomplamoose’s mashup of “Sweet Dreams” by Eurythmics and “Seven Nation Army” by the White Stripes:

Author’s note: If there’s a short story you’d like to see discussed in the coming weeks, please send your suggestion to label@nationalreview.com.