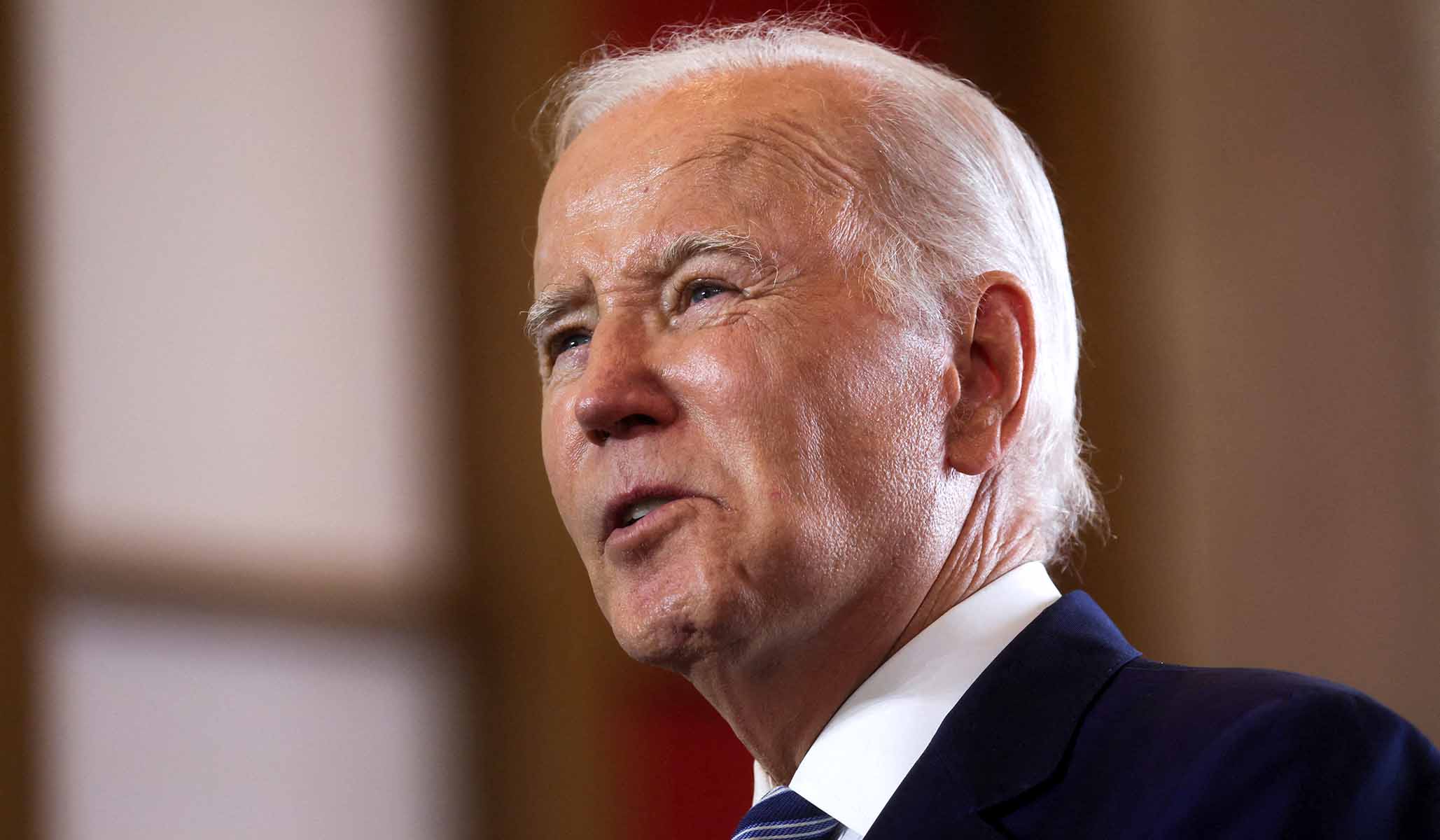

The Financial Times has run an article (the first of a two-part series) about President Biden’s industrial policy. Its title: “The new era of big government: Biden rewrites the rules of economic policy.”

For good or ill (spoiler: ill) that’s true enough, but I was surprised to read this in the course of the description of the construction of a new factory making lithium-ion batteries:

It is the kind of project that the White House wants to see sprout across the US, especially in the industrial areas that were ravaged during the globalisation era of the past four decades — a process which was facilitated by policies put in place by both Republican and Democratic presidents.

To blame this “ravaging” on globalization is to avoid mentioning the elephant in the room: automation. While it is true that, in certain sectors (such as textiles), globalization has hit U.S. manufacturers hard, it is not the culprit that it is often made out to be.

I touched on this topic in a recent Capital Letter. Responding to a piece by Patricia Cohen in the New York Times in which, among other points, she wrote that “in the United States and other advanced economies, many industrial jobs were exported to lower-wage countries, removing a springboard to the middle class,” I wrote:

To deny that some of that took place would be foolish, but the far greater killer of those industrial jobs has been technology. Writing for the New York Times in 2016, Claire Cain Miller quoted Lawrence Katz, an economics professor at Harvard. His view was that “over the long haul,” automation had been much more important: “It’s not even close.” She also cited analysis which attributed roughly 13 percent of America’s manufacturing job losses to trade and the rest to enhanced productivity because of automation.

In this connection, it’s worth paying at least some attention to the fact that manufacturing output has been growing for years, while the percentage of workers employed in manufacturing has been falling.

The impact of automation only makes one appearance in the FT’s piece:

In Buffalo, the Viridi battery plant now stands as a beacon of opportunity in a depressed area. But its workforce is a fraction of the thousands that once worked in the plant shut down by American Axle & Manufacturing 15 years ago. Automation is coming fast too, and robots won’t revive the area — or vote in elections.

True and true, and that reference to robots not voting in elections should be read as a reference to the political problems that increasing automation will bring or, I would argue, are already beginning to bring.

But back to the FT:

Four decades after Ronald Reagan rejected large-scale US government intervention in the economy, Biden is embracing it wholeheartedly with a raft of subsidies for domestic producers in strategic sectors, in the hope of creating hundreds of thousands of new jobs.

While it is true that Reagan largely rejected an expansion of government intervention in the economy (and was helped in that by the courts moving away from the old Brandeisian command-and-control interpretation of antitrust law) and significantly advanced the deregulatory push that was beginning in the Carter years, the extent of the state’s retreat is often exaggerated. That’s a discussion for another time.

But the FT’s writers are certainly correct to suggest that Biden’s approach to the economy is different from that of his predecessors, although whether some of the sectors the administration treats as “strategic” truly meet any benign interpretation of that word is another question. Some of the government’s investments in supposedly strategic “green” sectors are exercises in value destruction that might suit China’s strategic interests, but seem to offer little to those of the U.S.

Most interesting, perhaps was to read this:

“I don’t think you’ve seen something of this magnitude since Reaganomics came on the scene,” says Jennifer Harris, a former Biden administration official who worked on international economics at the White House National Security Council. “We’ve been living in that intellectual box and under those policymaking constraints for 40-plus years, and so this is really shaking those off towards the next turn of the screw.”

To use the phrase “an intellectual box” to describe a view of economic policy that, in principle anyway, involves giving more freedom to people to make their own decisions is curiously revealing. What Harris means, of course, is that giving people more opportunity to do their own thing put would-be technocrats and would-be planners, her “we,” in a box, or at least restricted their ability to meddle in some of the areas that interested them. Judging by the U.S.’s superior economic performance (compared with much of the world) in recent decades, that has been no bad thing.

Harris pops up again later in the article:

“I think the Biden camp really sees questions of trade and industrial policy as tools to a set of higher ends, or broader national aims, whereas [traditional Republicans and longtime Democratic policymakers] see markets as an end to itself,” says Harris.

It is true that some of these officials, such as technocrats and planners on the left (and, for that matter, the right) do see industrial policy as tools to achieve “higher ends” (normally they take it on upon themselves to decide what “higher” is) and “broader national aims” (once again, something they define). The more opportunist among them, however, see the pursuit of such aims and ends as a source of careers, power, and rich pickings, even as, in some cases, they convince themselves it’s in a good cause. Technocracy is a rent-seeker’s paradise.

As for those who would rather leave more of the economy to the operation of markets (the idea that they would leave everything to markets is a fantasy dreamt up by those who like to chatter about “free-market fundamentalists”), this not because they think that markets are an end in themselves, but because they believe that markets tend to be the best way of allocating resources. The unprecedented human flourishing that markets have enabled would suggest they are right.

That’s not to argue that markets are perfect, but, as John Cochrane recently put it in his blog (and which I quoted in the same Capital Letter):

The case for free markets never was their perfection. The case for free markets always was centuries of experience with the failures of the only alternative, state control. Free markets are, as the saying goes, the worst system; except for all the others.

In this sense the classic teaching of economics does a disservice. We start with the theorem that free competitive markets can equal — only equal — the allocation of an omniscient benevolent planner. But then from week 2 on we study market imperfections — externalities, increasing returns, asymmetric information — under which markets are imperfect, and the hypothetical planner can do better. Regulate, it follows. Except econ 101 spends zero time on our extensive experience with just how well — how badly — actual planners and regulators do. . . .

I have a nasty feeling that we are now adding to that experience, and that the usual grim results will ensue.