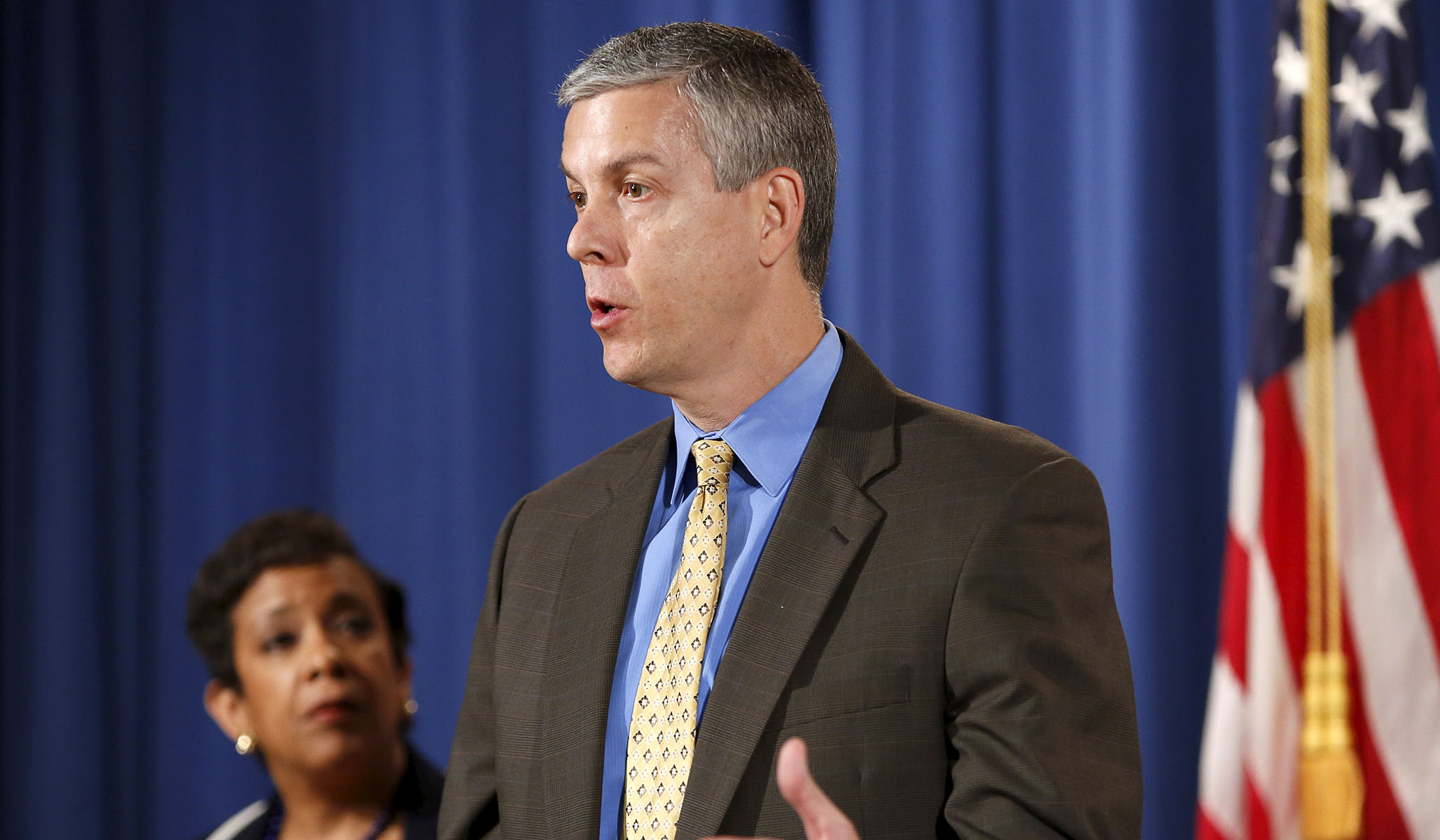

Former Education Secretary Arne Duncan prided himself on “never once” closing the schools he ran in Chicago before his ascension to Barack Obama’s cabinet. He knows “how important schools” are, particularly to “vulnerable children.” That exercise in throat-clearing preceded Duncan’s full-throated endorsement of closing schools down “during the epidemic.”

His was a defensible reflex at the outset of the Covid-19 outbreak, but Obama’s former education czar held fast to the view that schools were deadly petri dishes long after the benefit of the doubt expired.

“We have to invest [sic] our school system[s] still don’t have the PPE they need,” he said in late fall 2020. “They don’t have the cleaning supplies they need. We just need to have a major investment” — the tens of billions Congress had already appropriated for pandemic-mitigation measures in schools notwithstanding.

By spring 2021, Duncan dedicated himself to writing op-eds about “best practices and creative solutions to reopening schools,” which focused primarily on optimizing the technologies and standards that justified their perpetual closure. After all, he wrote, “Getting kids and teachers back to school is just the beginning and not enough.”

As school closures dragged on almost a year later, Duncan trained his ire not on the teachers unions’ and administrators perpetuating school closures but those who questioned the efficacy of the mitigation measures that had failed to reopen America’s schools.

“Have you noticed how strikingly similar both the mindsets and actions are between the suicide bombers at Kabul’s airport, and the anti-mask and anti-vax people here?” he wrote of the bloodshed produced by Joe Biden’s botched withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan. “They both blow themselves up, inflict harm on those around them, and are convinced they are fighting for freedom.”

Duncan thought the zinger so sophisticated he reprised it the following week when he alleged that going maskless in an educational setting was tantamount to homicide. “Please take a minute to fully understand this,” he implored, “our teachers are being killed right now at a much higher rate than our soldiers.”

No thanks to Arne Duncan, America’s schools did eventually reopen — a response to the receding threat posed by the pandemic as much as the open revolt of so many of the country’s frustrated parents. But the intervening months haven’t convinced Duncan of the value of in-person education — not when school closures can be used as leverage to pry some progressive political objective out of lawmakers’ hands.

“At what point do we consider a national boycott of schools, until our children are safe to learn there, and our adults are safe to teach?” Duncan wrote following the killing of three teachers and three children at a Christian elementary school in Nashville, Tenn. “How many lives need to be lost before we actually decide to do something, and keep everyone safe?”

In an interview with The Grio’s April Ryan following this call to action, Duncan acknowledged that such a boycott would demand a “massive sacrifice” from parents and “middle school, elementary, high school” students alike. But “sometimes it takes young people just like in the civil rights movement” to make a change.

This is not a novel suggestion from Duncan. In 2018, Obama-era education official Peter Cunningham floated the notion that “America’s 50 million school parents” should “simply pull their kids out of school until we have better gun laws.” Duncan thought the idea was “brilliant” and pledged fealty to the cause. “What if no children went to school until gun laws changed to keep them safe?” he pondered. “My family is all in if we can do this at scale. Parents, will you please join us?”

The answer Duncan got was a definitive “No.” School-age parents probably haven’t warmed to the concept now that we all understand what a world without in-person education looks like.

The consequences a generation of Americans will experience as a result of their prolonged absence from the classroom are hard to comprehend. Test scores have plummeted. Behavioral issues have spiked. Children’s mental health has deteriorated to the point of crisis. The scale of educational loss worldwide is “nearly insurmountable,” according to the United Nations. And American schools stayed closed longer than those in almost any other developed country.

None of that seems to matter to Arne Duncan. To him, in-person schooling is a carrot to be dangled before parents and students, only to be ripped away if they fail to advocate political outcomes he supports. Education is, to him, a luxury — one we cannot afford if it comes at the cost of progressive policy goals. For a former Education secretary, Duncan evinces little regard for education. If his instincts are shared by the rest of the educational establishment, that explains the pandemic-era torment to which millions of parents and students were subjected.