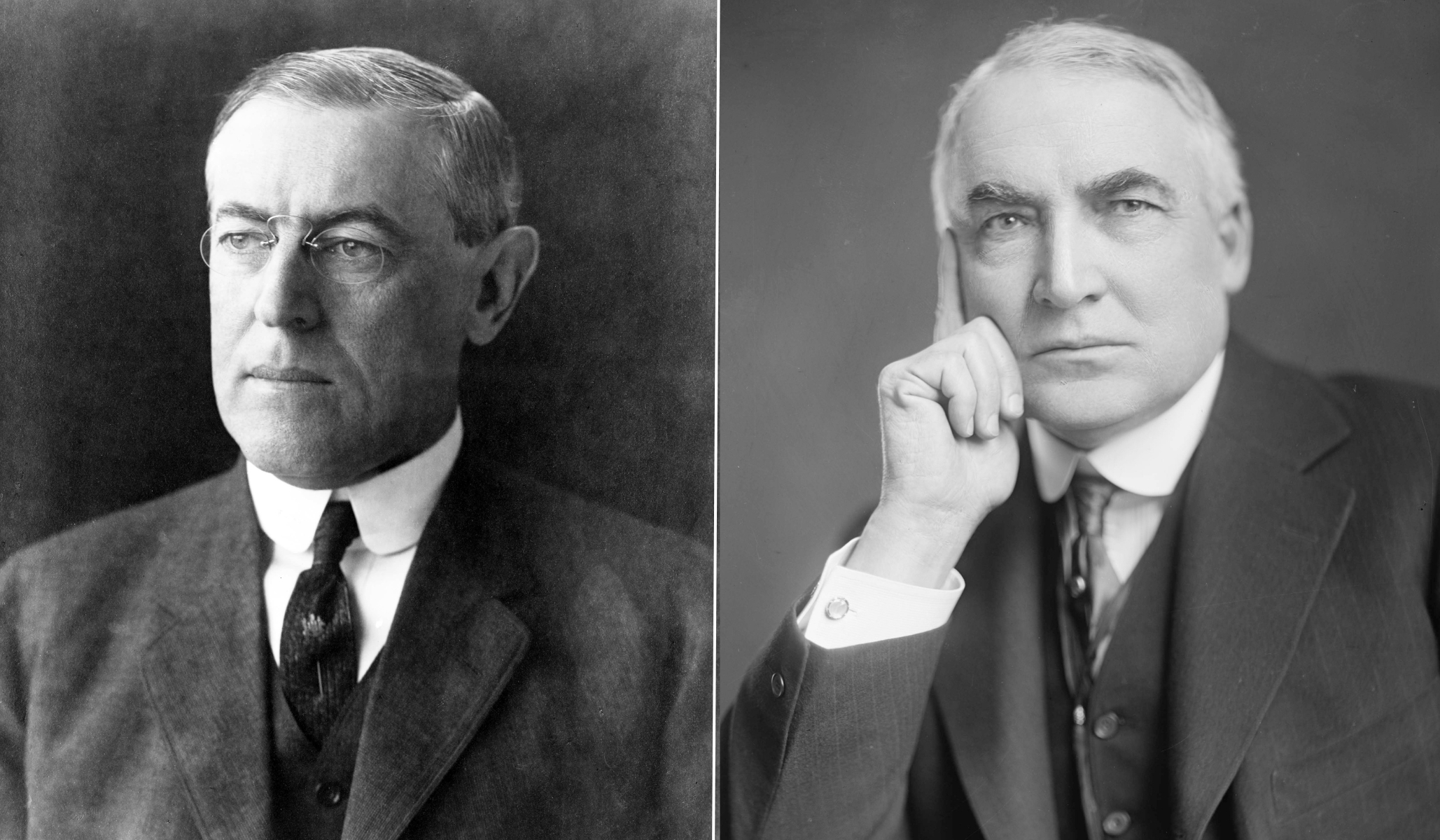

Woodrow Wilson was No. 28 and Warren Harding No. 29. If you ask most learned Americans about them, you’ll probably hear that Wilson was a pretty good president, while Harding was a very poor one. That notion stems from the way history is taught — presidents who expand federal power get high marks and those who don’t get low ones from historians.

Pushing back against that idea is Bob Graboyes in his latest Bastiat’s Window post.

Wilson was deeply racist and a thoroughgoing statist. He attacked the First Amendment and had dissenters such as Eugene Debs imprisoned. He brought the U.S. into a European war (after promising not to). He undermined the Constitution’s separation of powers. On the other hand, Harding pardoned Debs, reduced the scope and expense of the government, and got the country into no wars.

I particularly like Graboyes’s highlighting of a little-known speech Harding gave on race relations:

Harding gave the single most courageous speech on race relations ever delivered by an American president — and only a few months into his presidency. He was invited by an Alabama senator to give a speech in Birmingham. To the shock of the crowd (whites in front, blacks in back), he became the first president in history to address race relations head-on. While some of his verbiage is cringeworthy to our ears, in the context of the time his speech was a full-throated call for racial equality — absolutely revolutionary. In a hotbed of Klan activity, Harding declared:

“I can say to you people of the South, both white and black, that the time has passed when you are entitled to assume that the problem of races is peculiarly and particularly your problem, … It is the problem of democracy everywhere, if we mean the things we say about democracy as the ideal political state. … Whether you like it or not, our democracy is a lie unless you stand for that equality.”

I will only add that Harding had the good sense not to have the federal government intervene to “revive” the economy when the post-war recession hit in 1921. He ignored the interventionists and took the advice of Treasury secretary Mellon to just let the economy recover on its own. For those wanting to know more about that, I recommend James Grant’s book The Forgotten Depression.