The New York Times’s editorial board claims that the Freedmen’s Bureau Acts of 1865 and 1866 suggest that the Fourteenth Amendment allows discrimination based on race:

The chief justice has long adhered to this view of race. As he wrote in a 2007 case striking down race-conscious state programs aimed at integrating public schools, “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” It was a memorable line, because it flattered the commonly held belief that any race-based discrimination is not just wrong but unconstitutional.

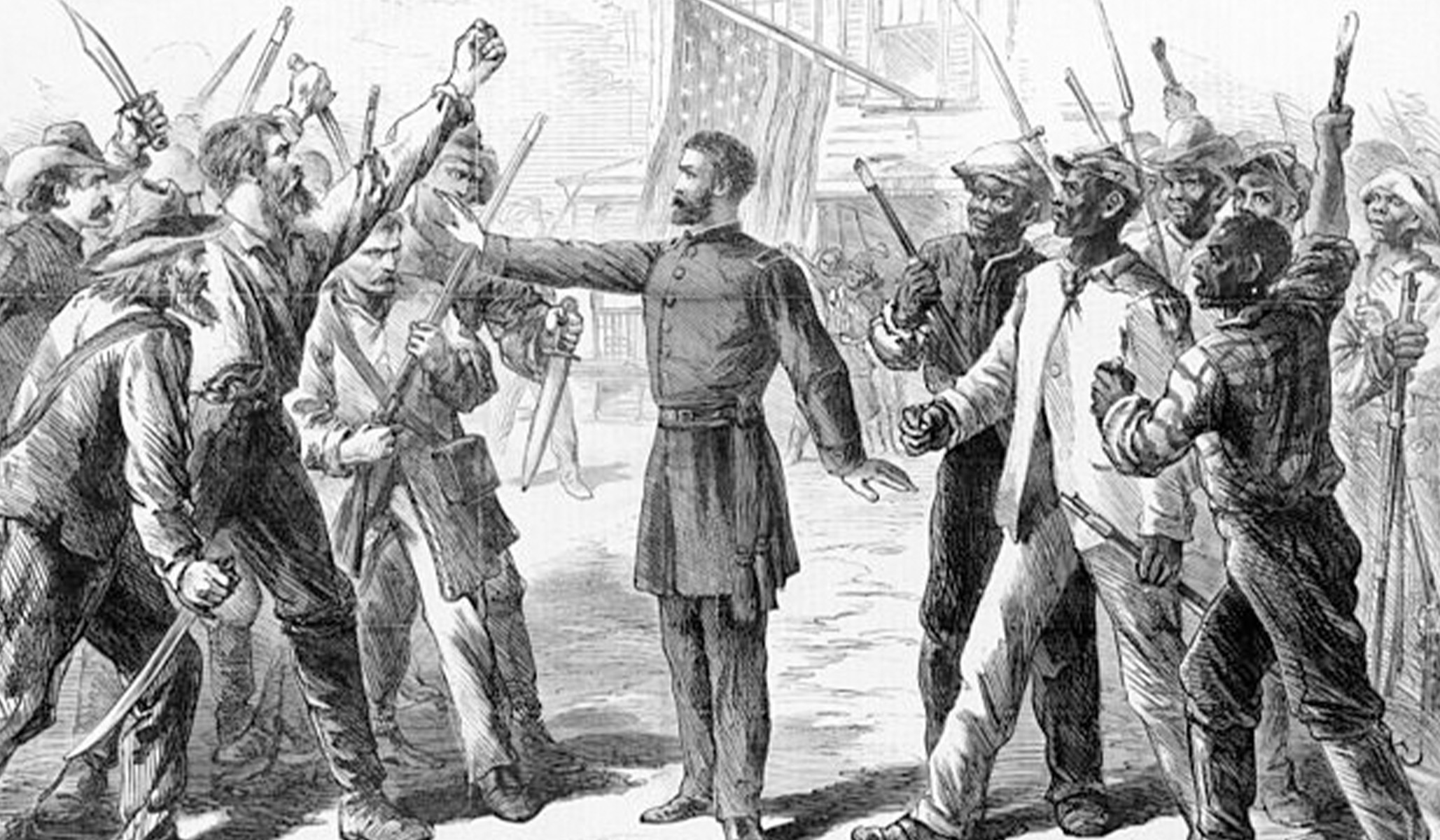

The problem is that, as a matter of history, it’s not true. The 14th Amendment, ratified in the aftermath of the Civil War, was expressly intended to allow for race-conscious legislation, as Justice Sotomayor noted emphatically on Thursday. The same Congress that passed the amendment enacted several such laws, including the Freedmen’s Bureau Acts, which helped former slaves secure housing, food, jobs and education.

The Times’s editors seem to believe that “former slaves” and “race-conscious” mean the same thing. They do not. Slavery was, of course, closely linked to race. Nearly nine-tenths of all black Americans in 1866 had been slaves in 1860, and many (although not all) of the rest had been slaves before that. But, as with the Three-Fifths Clause — which also applied to slavery rather than race — the two were not synonymous.

Notably, there is no mention of race in the Freedmen’s Bureau Act of 1865. The law mentions “a bureau of refugees, freedmen, and abandoned lands”; refers to “control of all subjects relating to refugees and freedmen from rebel states”; provides for “the immediate and temporary shelter and supply of destitute and suffering refugees and freedmen and their wives and children”; establishes the “authority to set apart, for the use of loyal refugees and freedmen, such tracts of land within the insurrectionary states as shall have been abandoned”; and offers land to “every male citizen, whether refugee or freedman” (but not otherwise).

Unlike the first, the second Freedmen’s Bureau Act does mention “race” and “color,” but only in the passages that reiterate Congress’s opposition to discrimination. When the law’s benefits are being outlined, the references are all to “freedmen” and “refugees” and their families. The statute refers to “a Bureau for the relief of Freedmen and Refugees”; notes that “the supervision and care of said bureau shall extend to all loyal refugees and freedmen”; mentions its applicability to “freedmen and loyal refugees, male or female” and to “loyal refugees and freedmen”; recommends “the education of the freed people”; proposes “the necessity and duty resting upon the government, and resulting from the condition of freedom, of aiding freedman to receive that needful education which oppressive prejudices, lies, and customs denied them when held in slavery”; and vows to “co-operate with private benevolent associations of citizens in aid of freedman.” When “race” and “color” are cited, they militate in the other direction — by (a) showing that the drafters could distinguish between slavery and race when they wished to, and (b) making it clear how keen they were to ensure that rights were protected, and funds were delivered, in what would now be called a “colorblind” manner. The Act confirms that “States which have made provision for the education of their citizens without distinction of color shall receive the sum remaining unexpended of such sales or rentals, which shall be distributed among said States of education purposes in proportion to their population.” It insists that “the constitutional right to bear arms, shall be secured to and enjoyed by all the citizens of such State or district without respect to race or color, or previous condition of slavery.” (You’ll note the “or” there, which distinguishes between “previous condition of slavery” and “race or color,” and thus shows that if its drafters had meant to apply to it on the basis of “race or color,” as opposed to “freedmen,” they would have done so.) And it offers “military jurisdiction over all cases and questions concerning the free enjoyment of such immunities and rights, and no penalty or punishment for any violation of law shall be imposed or permitted because of race or color, or previous condition of slavery, other than or than the penalty or punishment to which white persons may be liable by law for the like offense.” (Note the same.)

In his concurrence, Justice Thomas makes this precise point:

Importantly, however, the Acts applied to freedmen (and refugees), a formally race-neutral category, not blacks writ large. And, because “not all blacks in the United States were former slaves,” “ ‘freedman’ ” was a decidedly under-inclusive proxy for race. M. Rappaport, Originalism and the Colorblind Constitution, 89 Notre Dame L. Rev. 71, 98 (2013) (Rappaport). Moreover, the Freedmen’s Bureau served newly freed slaves alongside white refugees.

The New York Times‘s editorial board cites Sonia Sotomayor’s dissenting view as justification for its claim. I suspect that it is referring to this, in which she submits correctly that the Freedmen’s Bureau Act ended up helping more than only those who had been either slaves or refugees:

One such law was the Freedmen’s Bureau Act, enacted in 1865 and then ex- panded in 1866, which established a federal agency to provide certain benefits to refugees and newly emancipated freedmen. See Act of Mar. 3, 1865, ch. 90, 13 Stat. 507; Act of July 16, 1866, ch. 200, 14 Stat. 173. For the Bureau, education “was the foundation upon which all efforts to assist the freedmen rested.” E. Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863–1877, p. 144 (1988). Consistent with that view, the Bureau provided essential “funding for black education during Reconstruction.” Id., at 97.

Black people were the targeted beneficiaries of the Bureau’s programs, especially when it came to investments in education in the wake of the Civil War. Each year surrounding the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Bureau “educated approximately 100,000 students, nearly all of them black,” and regardless of “degree of past disadvantage.” E. Schnapper, Affirmative Action and the Legislative History of the Fourteenth Amendment, 71 Va. L. Rev. 753, 781 (1985).

But this doesn’t really help the case, does it? For a start, as Thomas notes, the Act “did not benefit blacks exclusively,” but was open to many white refugees, and is, as such, a poor analogy for affirmative action. That aside, the fact that some black Americans with no personal connection to slavery were caught up in a law whose incessantly-repeated-in-the-text purpose was to help freed slaves and their families does not mean that a law that applied only to those who were incidentally caught up in the effects of slavery would therefore be legal under the terms of a constitutional amendment that was ratified two years later. Sotomayor writes that “Black people were the targeted beneficiaries of the Bureau’s programs.” But it is far more accurate to say that “freedmen and refugees were the targeted beneficiaries of the Bureau’s programs,” and that some non-freedmen and refugees also benefited from its alms. It is extremely difficult to administer government aid at a large scale without over-including its recipients. Income thresholds capture people with no income but much wealth. Benefits programs invariably waste some money on fraudulent applicants. A good deal of defense spending goes to the wrong place. The Freedmen’s Bureau was dealing with a vast and immediate humanitarian crisis, and it proceeded as such. As we have seen in our own time, laws written in such circumstances often choose speed and efficiency in dispensing aid over a more rigorous process for vetting applicants. When, by contrast, Congress convened to draft the Fourteenth Amendment, its members knew they were writing for the ages, and they were more careful to avoid the sort of race-specific references that they had placed in prior statutes. To conclude, as the Times does, that because the narrow terms of the Freedmen’s Bureau Acts ended up catching other people, modern affirmative action must be legal under the Fourteenth Amendment is a stretch indeed.