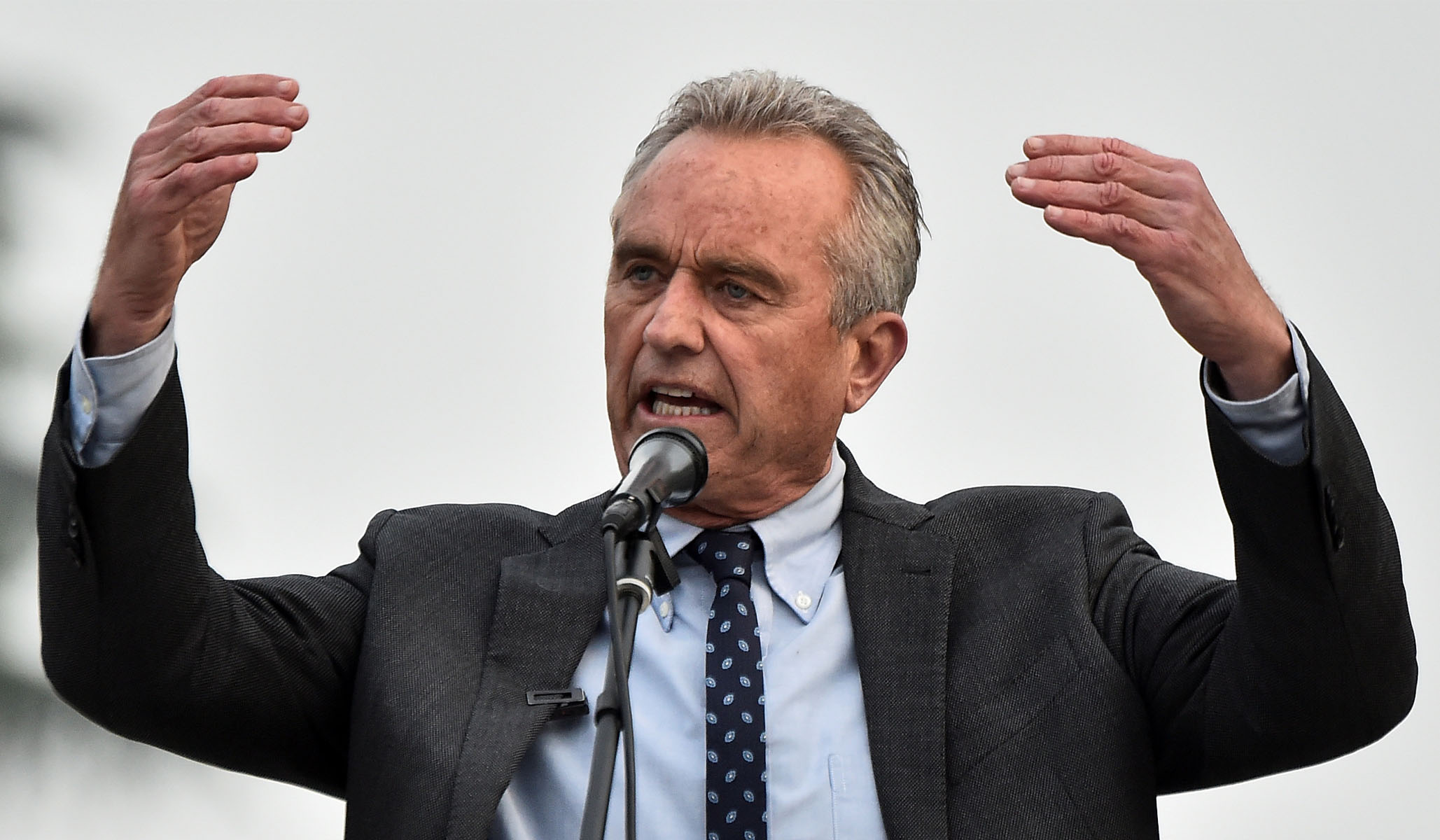

Michael writes of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s speech announcing his Democratic presidential campaign:

Kennedy invoked his years as what he called an “environmental advocate.” This highlights something about his tradition of liberalism. He rejected early offers to work on high-level environmental policy in Washington. Instead, he worked with organizations such as Riverkeeper, built on the activism of hunters and fishermen. “Hook-and-bullet people,” RFK called them. It is almost exactly the type of environmental organization that conservative philosopher Roger Scruton would have approved of, because it was built on the love of local people for their land and protective of the human livelihoods that depend on that land and the wildlife. He talks about the environment in the spirit of trusteeship. Pollution can create prosperity for a few in the present only by externalizing its costs generally, or to posterity.

For a sample of Scruton’s environmental thought, see here. One of its tenets is that, while environmental concern is welcome, even conservative, it is not best served by the state. He wrote of state solutions to ecological problems that they “are imposed from above; they are often without corrective devices, and cannot easily be reversed on the proof of failure,” adding that “their inflexibility goes hand in hand with their planned and goal-directed nature; and, when they fail, the efforts of the state are directed not to changing them but to changing people’s belief that they have failed.” Furthermore, he considered the state “the most effective instrument ever devised for externalizing the cost of individual actions” because “its impersonal, administrative and self-justifying nature makes it a perfect vehicle for absorbing the costs of my action now, and depositing them on the unknown others who will one day have to deal with my detritus.”

Given this, I wonder what Scruton would make of RFK Jr.’s environmentalist ambitions. In 2014, Ronald Bailey noted at Reason that RFK Jr. “magnanimously allows that individual Americans—even misguided souls who question the scientific consensus on man-made global warming—have a First Amendment right to speak their piece,” but “corporations and think tanks, however, are another matter.” RFK Jr. advocated an expansive reading of state laws that “maintain that companies that fail to comply with prescribed standards of corporate behavior may be either dissolved or, in the case of foreign corporations, lose their rights to operate within that state’s borders” that would enable the punishment of the companies he deemed “enemies of mankind.” He advocated that state attorneys general “withdraw state operating authority from the soulless, nationless oil companies,” such as ExxonMobil and Koch Industries, that funded conservative think tanks that dissented from prevailing consensus on climate change. But he went further than that, imploring “an attorney general with particularly potent glands” to “revoke the charters” of those think tanks, which he called “oil-industry surrogates” and “snake pits for sociopaths.” Among his offenders:

Cato Institute, The Heritage Foundation, Cooler Heads Coalition, Global Climate Coalition, American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), Americans for Prosperity, Heartland Institute, Committee for a Constructive Tomorrow (CFACT), George C. Marshall Institute, State Policy Network, Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI) and American Enterprise Institute (AEI).

Maybe the state-engineered liquidation of disfavored corporations and conservative think tanks will appeal to the populist Left. But I suspect Scruton, conservative conservationist though he was, might have had some reservations about RFK Jr.’s approach.