Our editorial this morning looks at the riot of left-wing culture wars and irresponsible spending that Minnesota Democrats have unleashed after flipping a single state senate seat in 2022 to gain unified but narrow control of the state government. How did things get so bad for Minnesota Republicans?

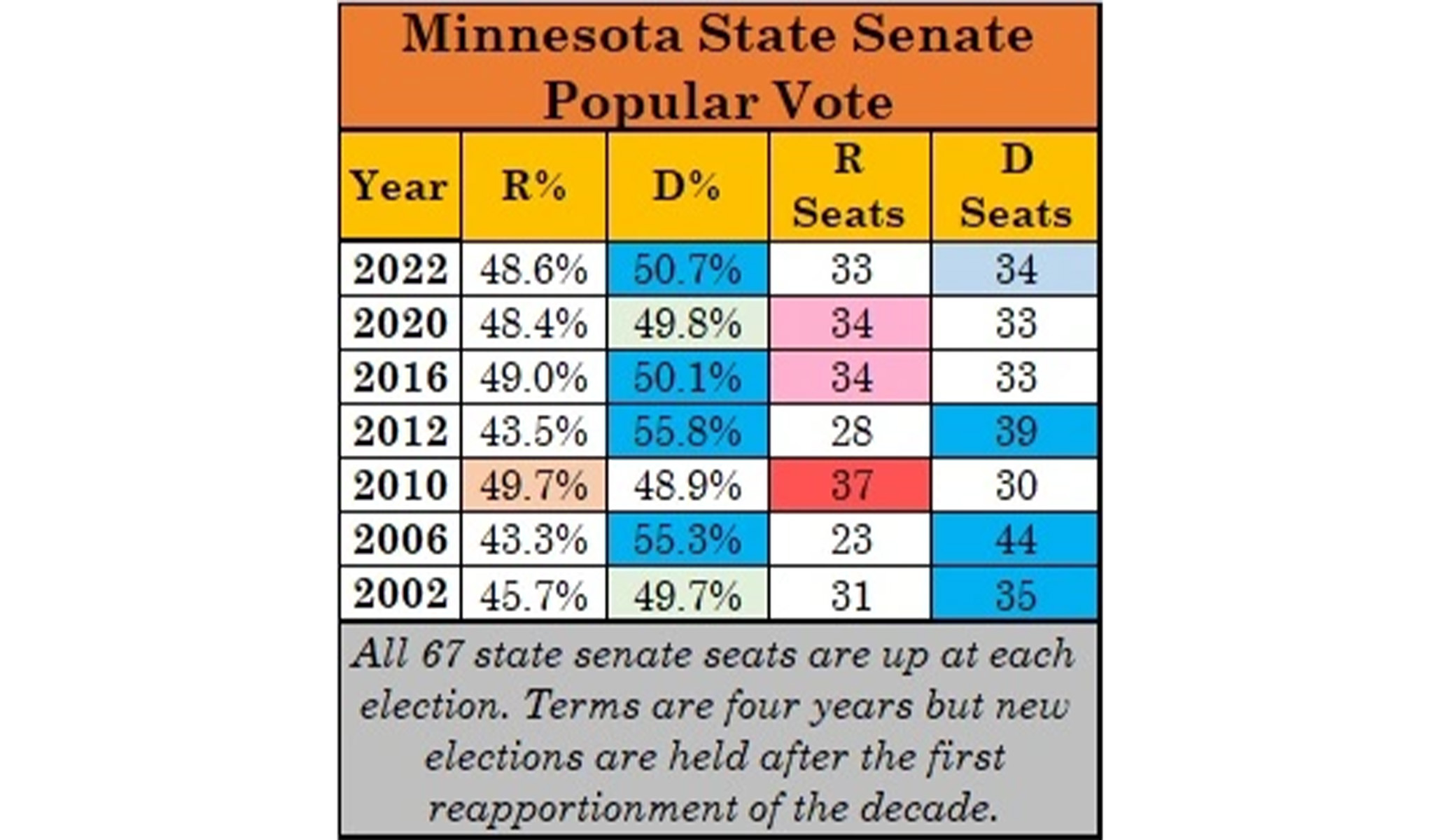

Part of the answer, of course, is that they weren’t that bad. Minnesota has an unusual system for electing its state senate, which provides for four-year terms but requires a new election in the second year of each decade, following reapportionment. Republican candidates got 48.6 percent of the vote statewide, a respectable showing that actually improved on 2020 and was in line with 2016, both years in which they won a majority of the seats. This was not the sort of national environment that led to Republicans getting blown out in state senate races in Minnesota in 2012 or 2006.

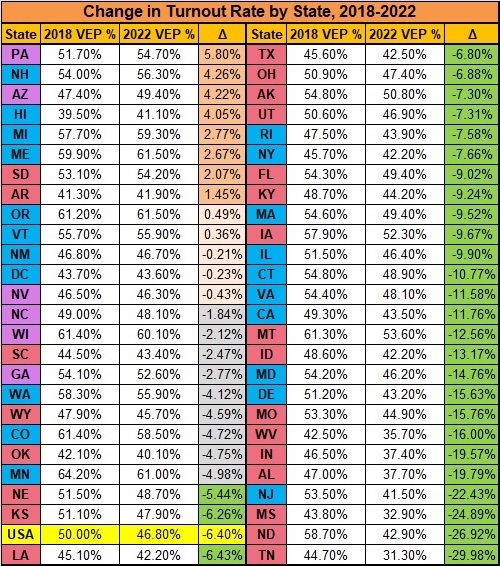

More broadly, if we look at the metrics I previously used in assessing 2022 turnout nationwide and in other states, turnout was down in Minnesota by around 5 percent from 2018. . . .

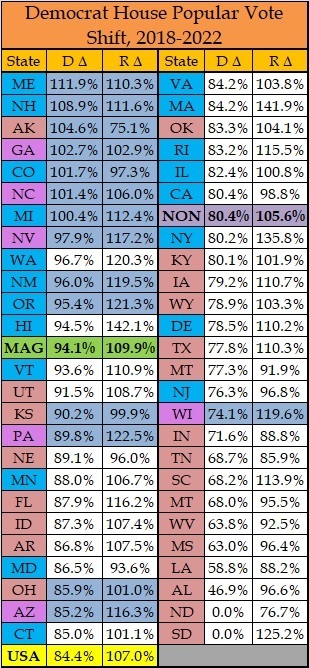

And in races for the house of representatives, there was a decided shift to Republicans in Minnesota compared with the prior midterm, as Democrat turnout was only 88 percent of their 2018 vote, while Republicans got 106.7 percent of their 2018 vote:

Even in the governor’s race, while Scott Jensen proved a poor challenger to Tim Walz, he still got 44.6 percent of the vote, which was the party’s highest since Tim Pawlenty’s 46.7 percent in 2006 and the second-highest since 1994. Of course, with a culture of high voter turnout and a tradition of third-party votes, raw percentages are perhaps less helpful than looking at the Republican share of the two-party vote, in which case Jensen’s 46 percent is lower than the Republican gubernatorial candidates got in 2010 or 2014 and lower than four of the past five Republican presidential candidates in Minnesota (the exception being John McCain in 2008).

Stepping back a bit, the general national trend leading into 2016 was for the areas outside of the big cities to become more Republican and the cities and the innermost suburbs to become stridently more Democratic. That trend was especially pronounced in the Midwest: It led to states such as Iowa and Ohio becoming much redder and states such as Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania being won by Donald Trump in 2016, being controlled by Republicans in the state legislature, and electing Republican governors (once in Pennsylvania, and for two terms each in Wisconsin and Michigan). Since 2016, the general trend has slowed, and it has been reversed in some places (again, especially those Midwestern states) by Republican weakness in the suburbs.

Republicans had reasons to think they were making headway in Minnesota, as in much of the Midwest. In five of the past six presidential elections, the Republican share of the two-party vote in Minnesota was within two points of the national trend, and it was more Republican than the country in 2016. Trump lost Minnesota that year by 1.5 points. But things have gone downhill for the GOP since then in the Gopher State. Why?

Obviously, Republicans started from a weaker position than in some of the other Midwestern states given the strong Democratic–Farmer–Labor tradition in some of the less urban parts of the state, particularly the Iron Range in the northeast (four counties in which were carried by Hillary when she was winning very few of the nonurban counties of the Midwest). And given the sheer size of the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, the DFL has a bigger urban base than in some other states, such as Iowa.

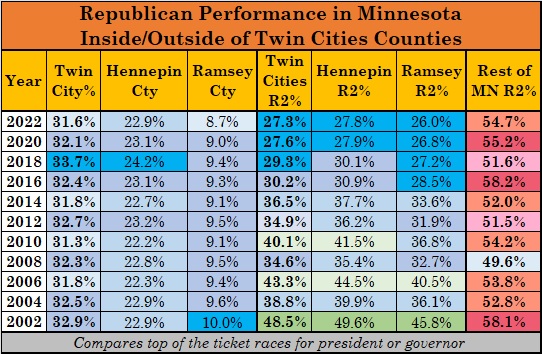

But Minnesota isn’t Illinois, where Chicago and its immediate suburbs dominate the state and where the rest of the state shrinks as a share of the state electorate as blue-state governance strangles and depopulates its communities. Let’s look at Minnesota presidential and gubernatorial elections since 2002 and divide the state into two parts — the counties of Hennepin and Ramsey (home to Minneapolis and St. Paul, respectively) and the rest of the state — using the two-party share of the vote:

A couple of things stand out. Republicans have, of course, lost the Twin Cities counties in each of these elections and won the rest of the state in all of them but the Obama–McCain race in 2008. But the demographic balance of the state hasn’t changed. For two decades, the share of the state electorate of the two Twin Cities counties has stayed relatively stable at just under a third. The Twin Cities counties accounted for their highest share of state turnout in 2018; that share was comparatively low in 2022, its lowest since 2014 and (in Ramsey) its lowest in two decades. So, the Republican problem isn’t that the state is dramatically urbanizing.

The reddening of the rest of the state has come and gone; Trump in 2016 did better than any other Republican presidential or gubernatorial candidate since 2002 outside Hennepin and Ramsey, eclipsing even the 58.1 percent of the two-party vote in the rest of the state for Pawlenty in 2022, which was a good Republican year. Jensen’s 54.7 percent of the two-party vote outside the Twin Cities counties was the best in a gubernatorial race since 2002, albeit weaker than either of Trump’s showings. But what has happened is that Hennepin and Ramsey have become dramatically bluer. Pawlenty almost carried Hennepin in 2002 and won 48.5 percent of the vote in those two counties that year. 2010 was the last time Republicans won 40 percent of the vote there; 2014 was the last time they won more than 35 percent; 2016 was the last time they won more than 30 percent. Jensen’s 27.3 percent of the vote across Hennepin and Ramsey was a new low. It’s a story we see elsewhere: Republicans can afford to lose the big cities, but if they are just getting massacred there, it becomes much harder to win a statewide race. Jensen, like Trump in 2020, wasn’t even competitive in the heart of the state.

Of course, Hennepin and Ramsey counties are not just the Twin Cities. Hennepin County is home to 1.267 million people, only a third of whom live in Minneapolis proper. St. Paul, with 307,000 people, is 56 percent of Ramsey County. In short, out of the 5.7 million people in the State of Minnesota, more than a million of them — almost 19 percent of the state population — live in the suburban portions of the Twin Cities counties.

It is one thing to write off big cities, but a Republican Party that loses the suburbs by 30 or 40 points is not long for this world. As is true in some of the neighboring states, Minnesota Republicans need to find a way to stop the bleeding in the suburbs if they want to remain competitive.