NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE T he mettle of any history class isn’t found in how teachers handle the “easy” stuff — it’s how they handle the most difficult and problematic episodes of the past. In this vein, Emma Green in a recent New Yorker article questions whether Hillsdale College provides an adequate study of the Reconstruction period of American history, suggesting that Hillsdale doesn’t directly address the prevalence of racial animosity and violence that took place following the U.S. Civil War and into the early 1900s. While it’s true that our American Heritage reader doesn’t currently include specific documents on Reconstruction, it’s fundamentally wrong to imply that we don’t teach this pivotal and harrowing period in our nation’s history.

First, we build on our pre-Reconstruction discussions of slavery and race, pointing out, for example, how Alexander Stephens’s “Cornerstone Speech” demonstrates the sobering degree to which slavery and race were woven into the fabric of the early republic. Indeed, we also discuss the fate of black Americans and the cruelty forced on them during the critical years following the Civil War and through the period of the civil-rights legislation of the 1960s. What we don’t claim, however, is a projected stance of mere victimization or passivity. With Wilfred McClay’s Land of Hope — our excellent companion textbook — we engage thoughtfully and authentically with issues of race and other critical elements of Reconstruction. In doing so, we reveal how both white and black Americans, immigrants, and American Indians were active agents of destiny.

In American Heritage courses, we give Reconstruction as much time as one can allot in a one-semester course that spans from the colonial era to the present day. Additionally, every year, three Hillsdale history professors — your two authors, alongside David Raney — have the great privilege of teaching “Sectionalism and the Civil War, 1848–1877,” one of several core courses for Hillsdale’s history majors.

Furthermore, Paul Moreno, dean of the social sciences and professor of history, teaches a two-semester course on constitutional history, focusing heavily on race in America. In one of his many publications, Moreno writes of black codes: “Behind these legal devices lurked such illegal means of controlling black competition as lynching and ‘whitecapping’ — terror to prevent black ownership or rental of land or the destruction of black businesses.” Professor Raney teaches a semester-long course dedicated exclusively to Reconstruction. In these various courses, we study and rely on the greats: Frederick Douglass, W. E. B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, Ida. B. Wells, Carl Schurz, Henry Adams, E. L. Godkin, Mark Twain, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Chief Joseph, Bruce Catton, Kenneth Stampp, Eric Foner, Herman Belz, Elliott West, Robert Higgs, Robert Utley, James McPherson, Allen Guelzo, Henry Louis Gates Jr., and Annette Gordon-Reed, to provide a sampling.

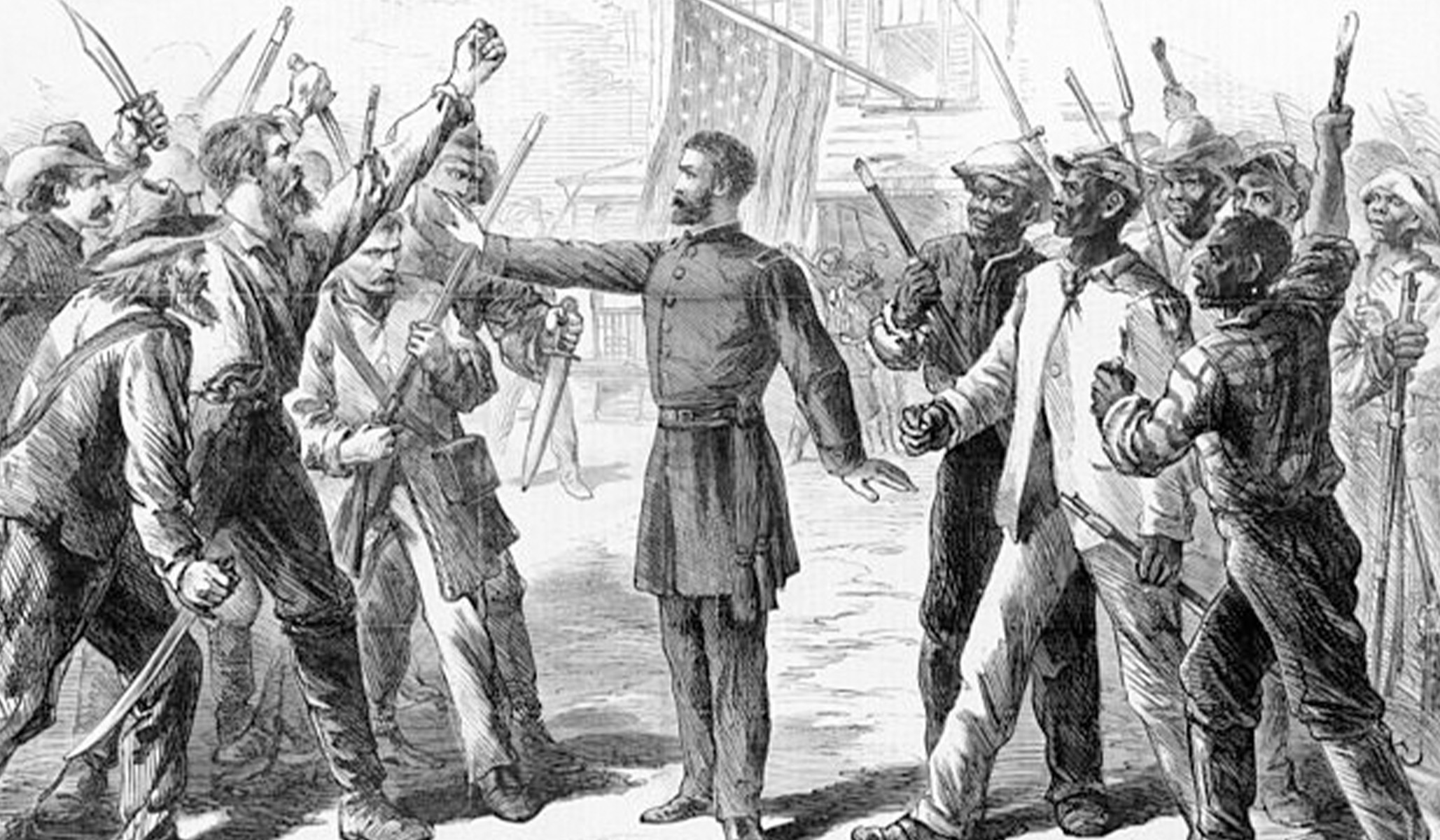

When we study Reconstruction with our students, we dive deeply into some of the most difficult questions that confront us as Americans. We discuss how, after the Confederacy’s defeat, government officials had to wrestle with the challenges of reinstating secessionist states into the union and of reintegrating the men of the rebellion into American society. We appraise how Lincoln’s initial soft reconstruction plans affected how Reconstruction played out. We also inquire into the roles played by the legislative and executive branches, especially exemplified by the Joint Committee on Reconstruction and the Johnson and Grant presidential administrations.

We convey to students that, while the Union secured victory in battle, the nation was still divided and embittered owing to the terror and loss endured during the war. More than 4 million emancipated slaves struggled to find a place in society. Many faced the choice of leaving their hometowns or dealing with prejudice from neighbors who remained pro-slavery. What’s more, the economic depression of 1873–77 stymied Reconstruction efforts. The aftermath of the Civil War reverberated throughout all areas of American politics and culture. The societal roles of white and black women changed. American Indians became the scapegoat of governmental brutality and politics. The rise of corporations altered big businesses and the U.S. economy. Our students learn all of this.

The historiography of Reconstruction changes rapidly enough so that even its most interested commentators can’t fully keep up with all the new arguments and academic literature. And while we’d never suggest that Hillsdale’s teaching of Reconstruction is perfect, we’d also never consent to the notion that our instruction is somehow inadequate. In a poignant way, we do well to recognize that the Reconstruction era is emblematic of the story of America itself — the journey of a still-young nation ever striving, amid trials and failure, to meet the high principles of its Founding.

Bradley J. Birzer is the Russell Amos Kirk Chair in American Studies and professor of history at Hillsdale College. Miles Smith IV is an assistant professor of history at Hillsdale College.