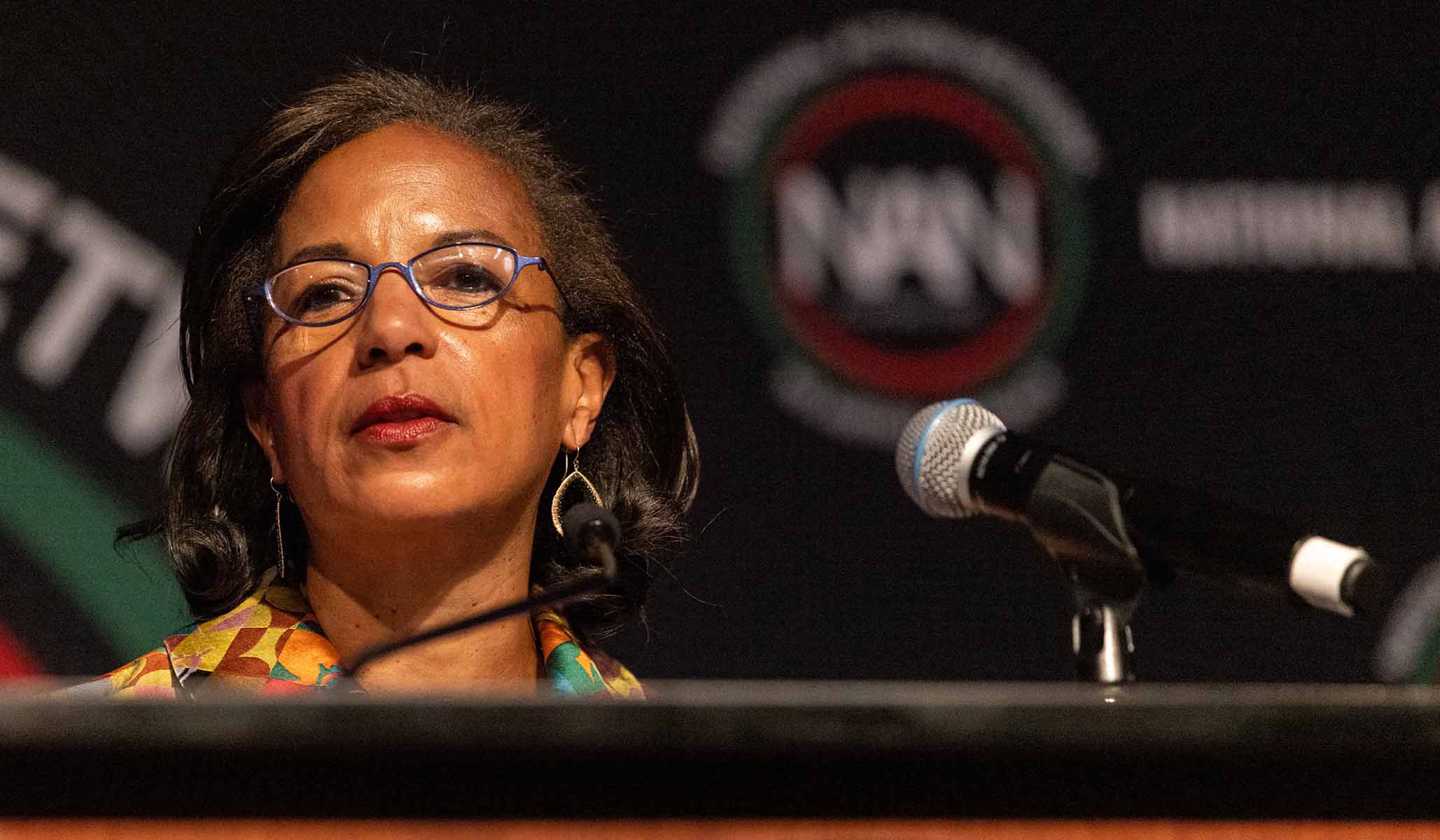

NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE M aybe it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Susan Rice, the director of Joe Biden’s Domestic Policy Council and the individual “charged with ensuring that the new administration embeds issues of racial equity into everything it does,” believes that racial equity is the answer to America’s foremost economic challenges. But in attempting to quantify the fiscal benefits we might enjoy if we shed our collective moral failings, the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) industry’s woman in the White House still manages to shock.

“In the last 20 years,” she told the audience at a gathering of Al Sharpton’s National Action Network this week, “the U.S. had a GDP shortfall of $16 trillion due to discrimination against black Americans. If we closed our racial gaps, we could add another $5 trillion to GDP over just the next five years.”

“That’s not my math,” Rice assured audience members. “That’s according to Citibank.” Indeed, those figures are a product of the work primarily done by Citigroup global economist Dana Peterson, who produced these estimates in 2020, and whose findings enjoyed uncritical coverage in the press and academia.

To describe a number of variables that contribute to Peterson’s estimates as complex would be a profound understatement. The report that forms the basis of Rice’s claims examines the effects on black Americans, over decades, of insufficient access to housing and home loans. It studies the intergenerational wealth foregone by those who cannot secure a college degree. It explores the costs of racial discrimination in hiring and in adversarial interactions with police. It considers the wealth not earned by lower- and middle-income black Americans and those of more means, including African-American Ivy League graduates who reportedly earn less than their counterparts, and by black entrepreneurs who struggle to secure venture-capital investment.

All told, Peterson estimates that, absent these “pyramidal” roadblocks to advancement, the U.S. could have created over 6 million new jobs in this century alone.

Given the bewildering number of inputs introduced into this analysis, it’s hardly surprising that other firms looking into the economic activity foregone by African Americans as a result of racial impediments have produced wildly divergent conclusions.

In 2019, the management-consulting behemoth McKinsey & Company pegged the GDP costs of the racial wealth gap, which limits rates of consumption among African Americans, at about $1–1.5 trillion over a decade. It reached this conclusion by adopting what it describes as the “optimistic assumption that black wealth grows faster than white wealth.” But that’s not the only eye-popping assumption in this report.

Exploring the home-ownership gap, McKinsey added that black-owned homes do not appreciate in value at rates seen by white homeowners — a gap that is not explained by “neighborhood differences and the quality of homes.” Only “racial animus can account for the remaining difference in appreciation.” Similarly, black families are less likely to own stocks than white families, “partly because black communities have historically struggled to trust the stock market.” Of particular relevance to Citigroup, the “relative lack of access to mainstream banking” and the “high availability of high-cost financial services” contributes to “a lack of trust in financial institutions” among a significant number of black Americans, who are “completely disconnected” from the banking sector.

The DEI industry is quick to cite itself as the remedy for at least some of these gaps. According to a report produced by the professional-services firm Accenture, American firms are sacrificing at least $1 trillion in profits by failing to be more “inclusive.” By failing to produce “a culture of equity,” as Accenture CEO Julie Sweet wrote, U.S. businesses contribute to a “perception gap” between employees and C-suite executives that reduces productivity and employee-retention rates. Bank of America Global Research sees the costs of racial avulsion running far higher. “Is it $70 trillion in foregone economic output? Or $23 trillion in USD GDP? Or $172 trillion in lifetime earnings?” a 2022 Bank of America report asked. “No matter how you measure it, lack of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) limits national economies and reduces GDP.”

As these disparities suggest, the legacies of discriminatory policies in the U.S. do put downward pressure on African-American incomes. And yet, it is impossible to separate social factors from those deriving from free personal choice to the degree necessary to produce an accurate assessment of racism’s macroeconomic effects. That was the conclusion of an academic joint session of the Allied Social Sciences Associations in 2021. As Brookings Institution scholars Randall Akee and Marcus Casey observed, “existing data sets have limited usefulness for identifying the breadth and scope of outcomes and instances of racism.” All we know for sure, according to Brookings Institution fellow Vanessa Williamson, is that eliminating the racial wealth gap requires a “program of heavy and highly progressive taxation aimed at the very wealthiest Americans.”

In lieu of a constitutionally fraught, racially discriminatory redistribution of income in this country, the DEI industry will have to suffice. Upon the release of the blockbuster report that Susan Rice cited, Citigroup also announced a plan to direct $1 billion toward closing the racial wealth gap. In 2021, the firm reluctantly assented to a “racial audit” of its policies — a measure that Citi executives attempted to block, arguing that the audit was unnecessary in part because of that well-intended $1 billion investment in black entrepreneurs and homeowners.

Citigroup is not alone. JPMorgan Chase & Co. made a $30 billion contribution to advancing racial equity in 2020 only to submit later to an audit of their efforts by PricewaterhouseCoopers — an audit that was deemed woefully inadequate by more-explicitly equity-focused auditors. Amazon appeared to have learned the rules of the road when it retained Obama-era attorney general Loretta Lynch to perform its review of the online retailer’s commitment to “address racial justice and equity.” Good intentions don’t speak for themselves, unless the relevant DEI stakeholders are given a taste.

Many firms, however, are ditching their DEI departments to cut costs amid increasingly challenging economic circumstances. No doubt, DEI advocates would cite America’s latent racial bigotries as the real impetus. “These layoffs show some CEOs weren’t committed,” said DEI consultant Dee Marshall ruefully of the layoffs targeting her industry. “Their priority was performative. It was, in some cases, business; it’s what they had to do for shareholders and stakeholders.”

To hear Susan Rice and others tell it, racism presents Americans with tangible costs that the country can’t afford. Their remedies to this condition involve imposing reparative costs on America’s most productive enterprises, which, it seems, those enterprises cannot afford either. The DEI industry’s prescription is a recipe for despair, at least for those Americans who aren’t getting a piece of the action.