Editor’s Note: What follows is an expanded version of a piece that appears in the current issue of National Review.

Few words are more confusing, or potentially confusing, than “liberal” and “conservative.” People mean different things by them. It’s helpful to find out what your interlocutor means, before proceeding in conversation with him.

You remember the U.S. presidential election of 1932. (Don’t you?) FDR and his men were calling themselves “liberals.” Hoover and his men were aghast: “No, we are!”

Conservative intellectuals such as Harvey Mansfield say that the purpose of the American conservative is to preserve the liberal tradition — i.e., the principles and ideals of the Founding. Other conservatives (self-described) consider the Founding a colossal mistake.

When it comes to conservatism, the question is, “What are you trying to conserve?” Back in the ’80s, we Reaganites were cross at the “mainstream media” because they were calling hard-line Communists in the Soviet Union “conservatives.” “See?” we said. “For the media, the bad guys always have to be ‘conservatives,’ whether they’re American or Soviet, anti-Communists or Communists.”

I hate to say it, but the “MSM” had a point: The Soviet hard-liners were conservatives, in that they were trying to preserve the Soviet system against Gorbachevian reforms.

Today, the big figures in the Republican Party regard themselves as staunch conservatives. (This goes for politicians and media personalities alike.) George F. Will, the veteran columnist, is different. Asked why he quit the Republican Party, he answered, “For the same reason I joined it: I’m a conservative.”

Churchill serves as an interesting case. He is a monumental British Conservative, who belonged to the Liberal Party for 20 years (1904 to 1924). In his biography of Churchill, Paul Johnson writes, “If Churchill was ever anything, he was a Liberal (as well as a traditionalist and a small-c conservative).”

In 1962, a member of parliament told Johnson a story. The MP had had an encounter with Churchill, now in his late 80s. As Johnson recounts,

the old man glared and said: “Who are you?” “I’m Bill Mallalieu, sir, MP for Huddersfield.” “What party?” “Labour, sir.” “Ah. I’m a Liberal. Always have been.”

William F. Buckley Jr. habitually wrote of “left-liberals,” sometimes “Left-liberals.” To put it briefly: He wanted to distinguish Hayek from John Kenneth Galbraith (WFB’s dear friend). Or he wanted to distinguish Galbraith from Milton Friedman (another dear friend).

Friedman dealt with this problem of words in the introduction to his book Capitalism and Freedom (1962, again). “Because of the corruption of the term liberalism,” he wrote, “the views that formerly went under that name are now often labeled conservatism.” But this was unsatisfactory, to Friedman.

He told the reader, or warned the reader, that he was going to stick with “liberalism.” He would use it “in its original sense — as the doctrines pertaining to a free man.”

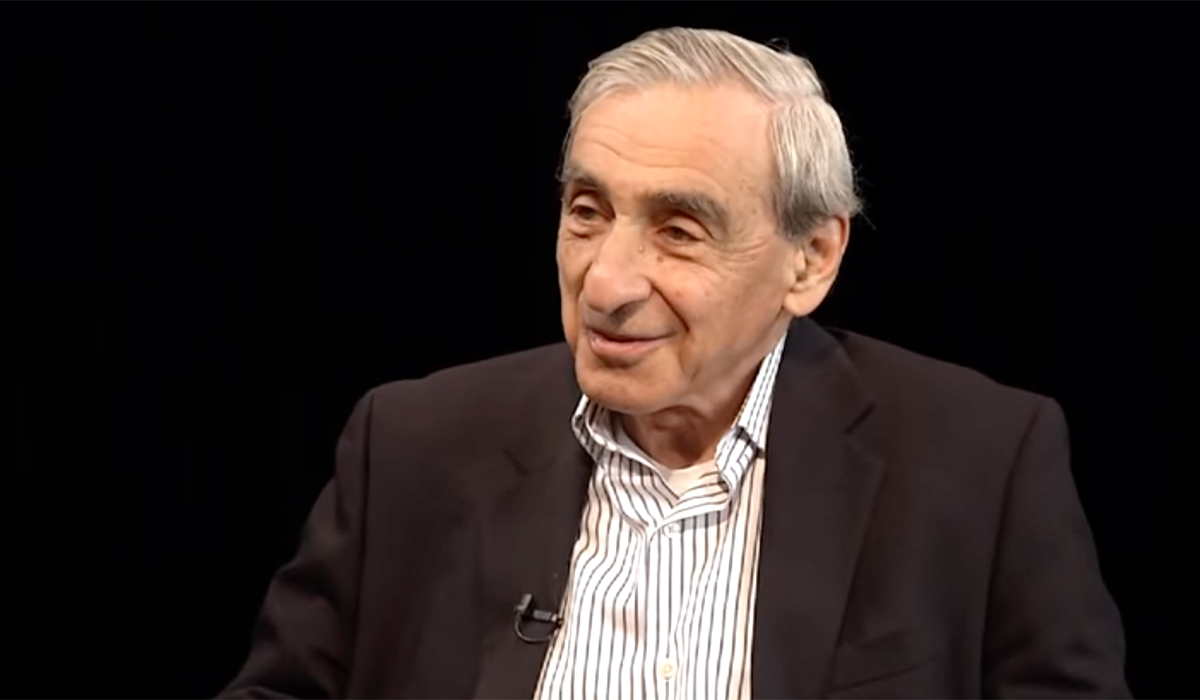

Michael Walzer is a liberal, but he’s no capitalist — in fact, he’s an anti-capitalist. But he is not really a liberal either. Rather, he is “liberal,” as he explains. A liberal what? More on that in due course.

Professor Walzer is one of the leading political thinkers and writers of our time. He was born in New York, in 1935. He went to Brandeis University and, for his Ph.D., Harvard. Supervising his dissertation was an outstanding liberal, Samuel Beer (who was also a teacher, and then a great friend and colleague, of Mansfield).

In the 1960s and ’70s, Walzer taught at Princeton and Harvard. In 1980, he joined the Institute for Advanced Study (in Princeton). He is now a professor emeritus. Since his undergraduate days, Walzer has been associated with Dissent magazine. One of its founders, Irving Howe, he regards as his mentor.

Whereas Beer was a major figure in Americans for Democratic Action, Howe was such a figure in the Democratic Socialists of America.

In 2002, Walzer published a wave-making essay, in Dissent: “Can There Be a Decent Left?” It was about U.S. foreign policy, and the Left’s critique of it from the Vietnam War onward. That critique, said Walzer, “has been stupid, overwrought, grossly inaccurate.”

Eighteen years before, Eugene D. Genovese, the great historian, had published his own wave-making essay in Dissent. It was his farewell to the Left — and an indictment of the Left, on his way out the door. He became a staunch conservative, in many respects. In “Can There Be a Decent Left?” Walzer did not turn his back on old friends and allies. But his independence was clear.

His new book, like the essay, has the word “decent” in its title: “The Struggle for a Decent Politics.” More interesting yet, however, is the subtitle: “On ‘Liberal’ as an Adjective.”

Walzer wrote this book during the pandemic. Lots of people had “pandemic projects”; this is his. It is dedicated to his wife, Judith Borodovko Walzer, “with whom I have been sheltering in place(s) for more than sixty years.”

The book is a little one, just 150 pages. It is conversational, casual, yet perfectly serious. The book is about the basics — the big and simple questions of politics — and sophisticated as well. It is madly learned. But it is pitched to the common reader (not that the author aimed for this — it just came out that way, I sense).

Walzer’s book reminds me of the one that George Will published in 2019: The Conservative Sensibility. Will’s is a big book, 640 pages, but I link the two nonetheless. The Conservative Sensibility is a kind of summa, a Ce que je crois. Will told me that he was thinking of calling it “Closing Argument.” He opted against, however, reasoning that he had a lot more writing to do. (This has proven true in the ensuing years.)

In the preface to The Struggle for a Decent Politics, Walzer says, “This may be my last book.” He has distilled, crystallized, what he has learned and believes.

The book has nine chapters. The first is headed “Why the Adjective?” The last is headed “Who Is and Who Isn’t?” In other words, who’s liberal and who’s not? In between are chapters on liberal democrats, liberal socialists, liberal nationalists and internationalists, liberal communitarians, liberal feminists, liberal professors and intellectuals, and liberal Jews. Walzer, as he says, is all of those things. His book is an explication.

So, what does he mean by “liberal”? This adjective, he says, has “pluralizing effects.” It tempers the dogmatic or absolute. It allows for difference, and the rights of people at large. Walzer believes that everyone should be liberal, whatever his noun or nouns are. The adjective may be of greater importance than the nouns.

Hang on a second: Is Walzer equating “liberal” with “decent”? I’m afraid he is. Conservatives will choke on this, of course, at least initially. But, as they read and ponder, they may swallow it, to a degree.

My mind runs to Robert Lucas, the economist, who died on May 15. His work has often been described as “revolutionary.” This did not sit well with him. “For myself, I do not have any romantic associations with the term ‘revolution.’ To me, it connotes lying, theft, and murder, so I would prefer not to be known as a revolutionary.”

In the writing of his book, Walzer had a couple of models. One of them is Carlo Rosselli, an Italian writer and activist who argued for “liberal socialism.” He was born in 1899 and died in 1937, murdered by his Fascist opponents. “Liberal socialism” may strike some as a contradiction in terms. But this was the politics of Clement Attlee, says Walzer — Attlee among many others.

Walzer’s other model is Yael Tamir, an Israeli intellectual and politician. In 1993, she published Liberal Nationalism, which began as a Ph.D. dissertation under Sir Isaiah Berlin, that luminous liberal (classical branch).

(A footnote, please. In a podcast last year, I asked George Will whether he had ever been starstruck. Plenty have been starstruck by him. It had happened to him only once, he answered — when, as a student at Oxford, he met Sir Isaiah.)

‘Democracy” is a word used by many, abused by many. The genocidalists of the Khmer Rouge renamed Cambodia “Democratic Kampuchea.”

Does “democracy” need “liberal” to be any good? I tend to think it does, but people left and right would disagree with me. Some lefties speak of “social democracy”; some righties speak of “illiberal democracy.” The latter is an Orbán phrase. In 2018, as he was launching his fourth term as Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orbán declared, “The era of liberal democracy is over.” In Hungary, yes — but the light of that democracy still shines elsewhere, for now.

About populists, Michael Walzer is terribly interesting, and not least when he is quoting Shakespeare. In Henry VI, Part 2, Jack Cade points to a cultivated man and says to the crowd, “Away with him, away with him! He speaks Latin.”

Is there anything — anything in all the world — that Shakespeare could not capture?

Of the populist demagogues who attain power, Walzer writes,

The first thing they want to do is to pass laws that ensure their victory in the next election, which, if they have their way, will be the last meaningful election. They attack the courts and the press; they erode constitutional guarantees; they seize control of the media; they violate the civil rights of opponents and minorities; they reshape the electorate, excluding those who, they claim, are not part of the People; they harass, repress, or arrest the leaders of the opposition — all in the name of majority rule.

That describes Hugo Chávez, the late Venezuelan, to a T. In 1998, he was elected fair and square — and that was it. He was probably the master populist of our time. AMLO in Mexico strains to keep up, as did Bolsonaro in Brazil. (Chávez’s successor in Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro, does not even try, ruling as a simple tyrant. It’s more honest, in a way.)

Here is some more Walzer, on “democracy” with an adjective:

I am not sure that what we called participatory democracy in the 1960s is an example of liberal democracy. In the political movements of those years democracy often amounted to the rule of the participants, which meant in practice the rule of the young militants who had time for all the meetings.

Professor Walzer, as you can taste in that passage, is wry. Throughout his book, he is wry, ironic, amusing. You get a sense of him in the epigraphs he chooses, before the book even begins. Here is one from Wisława Szymborska, the Polish poet:

So he wants happiness,

so he wants truth,

so he wants eternity,

just where does he get off!

Let us return to this business of “liberal socialism,” which sounds so strange to ears such as mine. “Liberal socialism has nothing to do with five-year plans, coerced uniformity, or a closing down of the space for individual initiative,” says Walzer. That’s good to know. A relief. “The aim instead is a pluralized economy and a more cooperative society so that citizens can recognize each other and engage with each other as equals.”

What would be our fates, if Walzer were czar? “. . . there are purchases that ought to be barred and others that are harmless.” We had better hear more.

If successful entrepreneurs can afford a more expensive vacation than I can; if they can collect first editions of rare books and I can’t; if they buy the newest fashions and I am hopelessly unfashionable — all of that is compatible with a just society. But if they can buy medical care that isn’t available to me; if they get legal representation in civil and criminal cases that I don’t get; if they have influence with government agencies that I don’t have — that is unjust.

It is safe to say that Professor Walzer would not have us in camps. The “liberal” that modifies him is real. Others on the left — and right, for that matter — I would beware.

Nationalism is a topic du jour, and of every jour, I imagine. Walzer’s chapter on the subject is enlightening. In a recent podcast, I discussed nationalism with Natan Sharansky, the politician, writer, and, above all, human-rights hero. Or rather, he brought it up with me, when I asked about the Ukrainians, and the stand they are taking against their invaders and would-be conquerors.

“They are bringing back to the word ‘nationalism’ its positive meaning,” said Sharansky. For many years, he has argued that Israel, his country, can be both Jewish and democratic. In 2008, he published a book titled “Defending Identity: Its Indispensable Role in Protecting Democracy.” For understandable reasons, “nationalism” is a touchy word in Israel, and nationalism a touchy subject.

“By their struggle,” says Sharansky, “the Ukrainians are showing what a good nationalism is. At the same time, Russia demonstrates the worst of nationalism” — the nationalism by which a “cruel dictator” strengthens his grip on the people under his “control.”

In his relevant chapter, Walzer writes, “People calling themselves cosmopolitans condemn all nationalisms.” Frankly, I have never heard anyone call himself a “cosmopolitan.” Maybe I should get out more.

Never is Walzer more interesting than he is on education. (An educator ought to be interesting on education, you could say.) Let me give you a reminiscence — from him:

I remember a high school civics teacher who, having brought us too quickly through the textbook on constitutional democracy, with two weeks left in the semester, ordered us to memorize the glossary of terms.

Walzer relates this reproachfully. He is criticizing “the rigidities of traditional schooling: authoritarian teachers, tight classroom discipline, and rote learning.” I have to tell you: I wish I had been put through that exercise — the memorizing of the glossary. That strikes me as an excellent serving of vegetables, good for the mind.

À chacun son goût, as the French teacher would have said.

Walzer spent many years in the classroom, teaching political theory. He says that he always took care to “alert students to the strongest arguments against my own position.” He adds, “That is not something that I would do at a party or a movement rally; it is a professional, not a political, obligation.”

Have some more Walzer:

We should never act in ways that would lead untenured teachers and vulnerable graduate students to think that they must conform to some ideological standard. Faculties are not political organizations.

And a bit more:

Given the long history of disagreement in almost every academic field, departments that merit the adjective “liberal” will be pluralist and inclusive.

When they were colleagues at Harvard, Walzer and Robert Nozick co-taught a course on capitalism and socialism. That was worth the price of admission, or tuition, no doubt.

Walzer may not like to hear me say this, but I believe he is, at heart, anti-“woke.” He has no time for student snowflakes who melt every time they hear something they don’t like. He has no time for professors who use their academic lecterns for political hectoring or bullying. And he has no reluctance to poke fun at certain pieties — as in,

I remember a time when you couldn’t publish an article in one of the leading journals of political theory unless it had at least four footnotes to Giorgio Agamben (I am exaggerating, but that’s how it felt).

On reading this, I thought of a composer, who years ago told me the trick of getting a grant: “Tell them you’re going to incorporate gamelan,” from the Indonesian tradition. “The check will arrive the following week.”

There is much for a conservative to like about Michael Walzer. Do you remember Florence King? “If Christopher Hitchens is a Marxist, I want to be one too.” But there is plenty to dislike as well.

For the life of me, I don’t understand why people — even the estimable Walzer — equate FDR’s Court-packing scheme with President Trump’s nomination of conservatives to the federal judiciary. Every president nominates people with whom he is in sympathy — Obama, Trump, Biden, all of them.

“I doubt that there can be a liberal capitalism given the inequalities that capitalism produces and the coercion it requires to keep workers in line,” Walzer writes. I think this is nuts. For one thing, who can out-coerce a socialist? But I will listen to Walzer. He is a bona fide teacher, and I hope not to be a snowflake.

I’m surprised that Walzer capitalizes “black” and “white,” in reference to Americans. That strikes me as . . . semi-illiberal. I hope the author will reconsider for the next edition. He’ll want to know, too, that Bret Stephens spells his first name unusually, not the conventional “Brett.” And “principle” versus “principal” always bears watching.

Warts and all, this is a lovely, deep, provocative book. It stimulates a hundred thoughts in you, on every page. I marked up my copy like mad. I think I wrote more words, in the margins, than Walzer did in his whole little book. Anyone willing to learn from Walzer — whatever the reader’s political disposition — will.

I get what he means by “liberal,” easily. I must say, however, that I’ve grown frustrated with words: political words. We live in a blizzard of nouns and adjectives: “social democracy,” “national conservatism,” “illiberal democracy,” “national socialism” (oops) . . . Tell me what your ideas are, designations aside. And may those ideas be humane and freedom-tending.