NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE N o one denies that our southern neighbor Mexico is plagued by drug cartels that pump fentanyl across our border, cronyism that smothers economic growth, and rampant corruption.

But one thing Mexico can be proud of is its National Electoral Institute (INE), an independent, nonpartisan but government-funded organization. It was formed in the 1990s as disgust with the country’s authoritarian rule and the accompanying voter fraud became so pervasive that reforms were implemented. Mexico’s transition from one-party rule to the peaceful transfer of power to an opposition party in 2000 was enabled in large part by the trust people had in the INE.

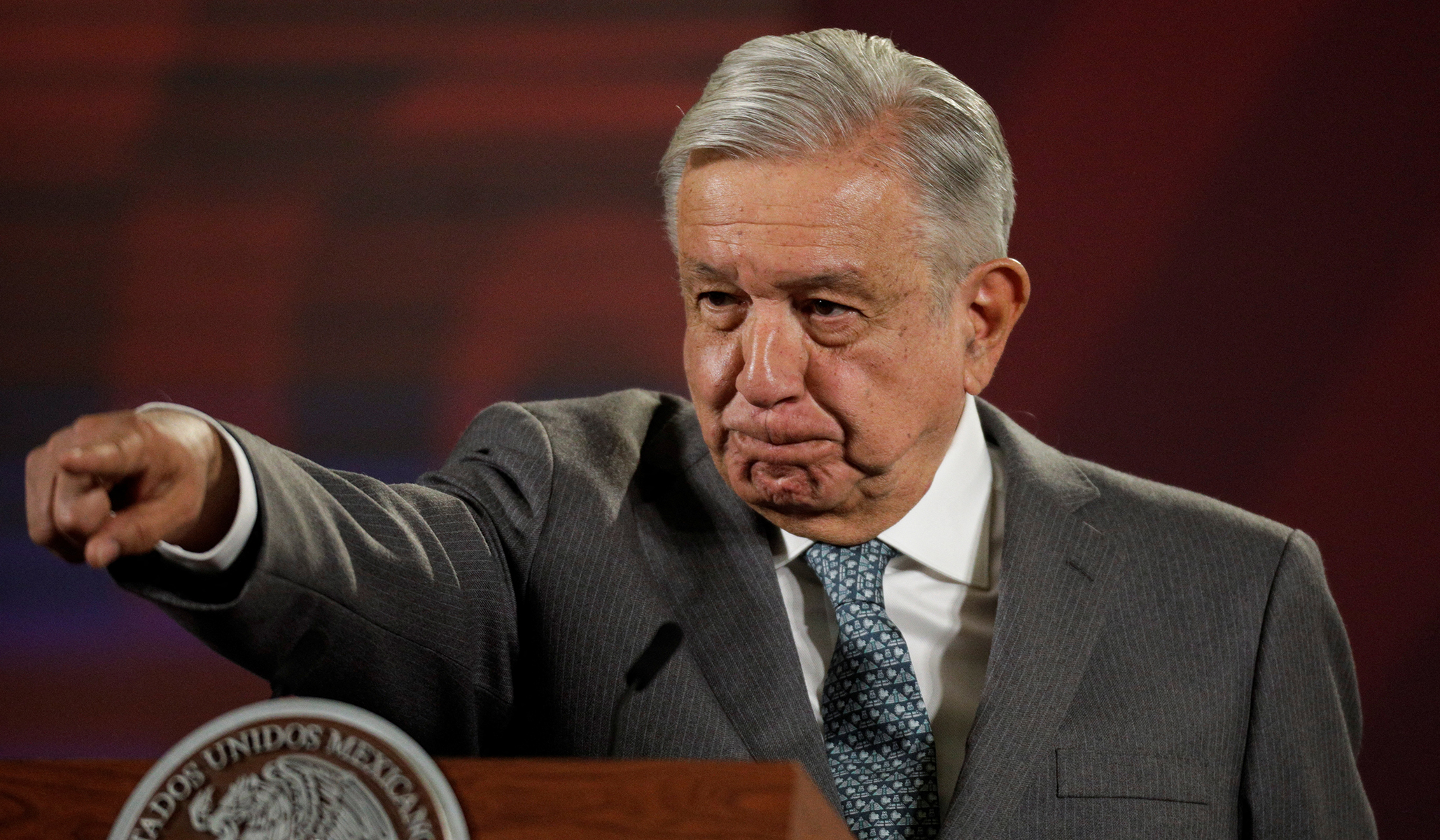

But Mexico’s term-limited president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, is trying to neuter the INE so he can ensure that a loyal sycophant will succeed him when he leaves office next year. His plan would slash the INE’s budget and limit its supervisory powers. Some 85 percent of its staff would have to be let go.

That could have catastrophic effects on whether a future election result stands. INE official Ciro Murayama told the Atlantic magazine that “the law establishes that if 20 percent of the polling stations in one election are not installed, that election should be annulled. It never happened in our history.” A lack of staffing could lead to such an annulment for the first time in over 100 years.

López Obrador is deadly serious about steamrolling his plan into law. He has nursed a grudge against INE ever since it presided over his narrow loss in the 2006 presidential election. The Mexican Senate voted 72 to 50 last month to curb the INE, prompting opponents of the bill to challenge it in the Supreme Court.

Mexicans are outraged, with more than 500,000 people jamming the streets of Mexico City in February to protest. López Obrador, a leftist demagogue, accused protest leaders of having “been part of the corruption in Mexico, they have belonged to the narco-state.”

Ironically, López Obrador has also descended to gaslighting his fellow citizens by declaring that the highly respected INE has ignored “the stuffing of ballot boxes, falsification of election records, and vote buying.”

“Let them go cheat somewhere else, they just want to keep stealing votes,” he said.

In reality, Mexico has an election system that is far more secure than ours. To obtain voter credentials in Mexico, a citizen must present a photo, write a legible signature, and give a thumbprint. To guard against tampering, the voter card includes a picture with a hologram covering it, a magnetic strip, and a serial number. In the United States, at a time of heightened security and rules that require citizens to show identification to travel or enter a building, states representing half of the country’s population don’t require any form of documentation in order to vote.

It’s encouraging that liberal groups such as the Brennan Center, which never met a voter-identification law it could support, have come to the defense of the INE’s anti-fraud and honest-election mission. A strong critic of the often-preposterous election claims of Donald Trump, it nonetheless noted that “the attack by a leftist president on Mexico’s independent electoral body is a reminder that resurgent authoritarianism can come from both the right and the left.”

Others on the left have fallen into a party line. The U.S. socialist magazine Jacobin called criticism that López Obrador is undermining democracy “a baseless charge.” The INE “is widely recognized to be riddled with excess expenditure and a top-heavy bureaucracy,” it added. “The new law simply mandates similar cost-saving measures to those that the administration of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has applied to other governmental departments.”

Cleta Mitchell, a legal fellow at the Conservative Partnership Institute in Washington, says Mexico’s struggle mirrors the one that blocked President Biden’s plan to effectively nationalize U.S. elections. Biden’s plan almost became law in 2021 but was blocked by renegade Democratic senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema.

“In the 1990s, Mexico had a set of laws enacted by one party to ensure their continued rule,” Mitchell told me. “That’s what I think about whenever I hear about another one of our blue states enacting laws to protect their power permanently. It is nothing short of tyrannical. And it is happening all across our country today.”