NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE T he Supreme Court on Thursday decided Twitter, Inc. v. Taamneh and Gonzalez v. Google LLC, a pair of cases involving the liability of social-media platforms for speech on their platforms: Do they have a responsibility to moderate and restrict it? Do they become more responsible when their user algorithms help drive readers to some speech over others? As I discussed when the Court took the two cases, the Ninth Circuit said yes in broad terms to both questions in both cases:

Gonzalez v. Google LLC is a lawsuit against Google by a man whose daughter was murdered by ISIS. He cannot, owing to Section 230(c)(1), sue Google for hosting ISIS recruitment videos on YouTube, but his legal theory is that Google’s algorithms that recommend videos on YouTube are Google’s own speech. . . . A loss for Google would have significant implications for the entire business model of search engines and social-media companies (especially TikTok) that depend on algorithmic recommendation to serve up both user content and advertising. . . . Twitter Inc. v. Taamneh . . . did not even address Section 230. It is also a lawsuit by victims of a terrorist attack, who argued under Section 2333 of the Anti-Terrorism Act, 18 U.S.C. § 2333, that the social-media platforms should have done more to stop ISIS recruitment by censoring content.

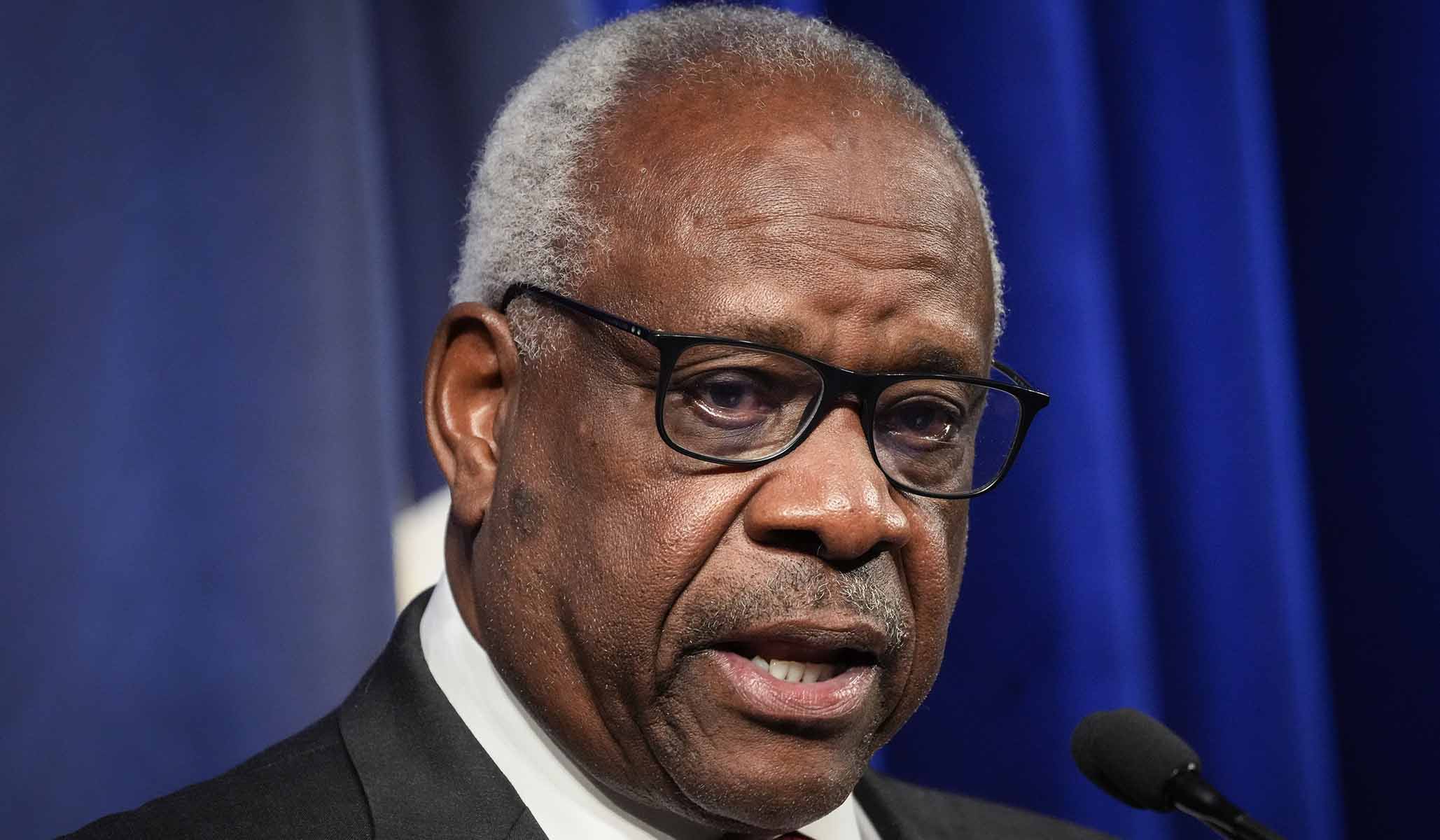

The Court’s unanimous answer in both cases was no: Even when the content at issue is literally terrorist-recruitment videos, proof of something more substantial than hosting and automated recommendation is required in order for the platforms to be liable for the speech of others. The Court reached that decision, in a majority opinion written by Justice Clarence Thomas in Taamneh, by going back to the traditional principles of the common law in defining civil “aiding and abetting.” Its approach should tell us something about how best to address the social-media giants going forward.

The Flexibility of the Common-Law Tradition

Thomas is known for his originalism and textualism, but how much specific guidance those approaches give to judges varies by the language used by Congress or the Constitution. The statute involved in Taamneh left a lot of room for the judiciary to fill in the details, but not without some important signposts in the common law. The Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act of 2016 (JASTA) amended 18 U.S.C. § 2333 to allow victims of terrorism to sue anyone “who aids and abets, by knowingly providing substantial assistance, or who conspires with the person who committed such an act of international terrorism.” (Emphasis added)

This statutory language happens to track carefully the common-law elements of civil aiding and abetting. As Thomas wrote, “terms like ‘aids and abets’ are familiar to the common law, which has long held aiders-and-abettors secondarily liable for the wrongful acts of others. . . . We generally presume that such common-law terms bring the old soil with them.” (Alterations omitted) For good measure, Congress specified that it intended “the proper legal framework” to be drawn from a 1983 D.C. Circuit opinion, Halberstam v. Welch. Halberstam’s pedigree commanded bipartisan respect: The opinion was written by Patricia Wald, a Jimmy Carter appointee who later became that court’s chief judge, and it was joined by the two other members of the panel, Robert Bork and Antonin Scalia.

Notwithstanding Scalia’s famous dictum that the rule of law should be a law of rules, preferring bright lines whenever possible, Halberstam used a six-factor test:

Those factors are (1) “the nature of the act assisted,” (2) the “amount of assistance” provided, (3) whether the defendant was “present at the time” of the principal tort, (4) the defendant’s “relation to the tortious actor,” (5) the “defendant’s state of mind,” and (6) the “duration of the assistance” given.

The decision itself, however, cautioned against treating these as “immutable components.” Thomas agreed: “By their very nature, the concepts of aiding and abetting and substantial assistance do not lend themselves to crisp, bright-line distinctions.” The judicial role, in such cases, is to allow for the development of a coherent body of law that applies the same general concepts to very different fact patterns without becoming a standardless permission for creative lawyering.

Thomas emphasized that Halberstam should be treated more like a common-law case than like a statute. That means that courts applying Halberstam should draw more expansively on the traditional common law and analogies to the facts of Halberstam rather than either treat its six-factor test as a checklist or require a precisely similar fact pattern:

JASTA itself points only to Halberstam’s “framework,” not its facts or its exact phrasings and formulations, as the benchmark for aiding and abetting. . . . Any approach that too rigidly focuses on Halberstam’s facts or its exact phraseology risks missing the mark. Halberstam is by its own terms a common-law case. . . .

At bottom, both JASTA and Halberstam’s elements and factors rest on the same conceptual core that has animated aiding-and-abetting liability for centuries: that the defendant consciously and culpably participated in a wrongful act so as to help make it succeed. . . . The phrase “aids and abets” in §2333(d)(2), as elsewhere, refers to a conscious, voluntary, and culpable participation in another’s wrongdoing.

Not only had traditional aiding-and-abetting principles grounded aiding-and-abetting liability in two major requirements — knowing participation and substantial assistance — but “courts often viewed those twin requirements as working in tandem, with a lesser showing of one demanding a greater showing of the other.” Put otherwise, “Less substantial assistance required more scienter before a court could infer conscious and culpable assistance.” In some cases, “a secondary defendant’s role in an illicit enterprise can be so systemic that the secondary defendant is aiding and abetting every wrongful act committed by that enterprise,” but when dealing with lawsuits against a business that dealt with the criminal only at arm’s length, the opposite is likely to be true.

The Common Law Didn’t Punish the Common Vendor

Thomas stressed that the common-law rules, however flexible they might be in reaching different types of misconduct, have always been read to protect businesses, merchants, and laborers from being blamed for crime simply because they sold goods and services to the general public, members of which they might suspect to be criminals. It also was not intended to punish “innocent bystanders” who witnessed a crime and failed to stop it, unless they violated some specific legal duty to act.

If aiding-and-abetting liability were taken too far, then ordinary merchants could become liable for any misuse of their goods and services, no matter how attenuated their relationship with the wrongdoer. And those who merely deliver mail or transmit emails could be liable for the tortious messages contained therein.

Noting the vast quantity of content posted to social-media platforms, Thomas rejected the view that the platforms should be treated differently than more traditional vendors or other providers of communication:

It might be that bad actors like ISIS are able to use platforms like defendants’ for illegal—and sometimes terrible—ends. But the same could be said of cell phones, email, or the internet generally. Yet, we generally do not think that internet or cell service providers incur culpability merely for providing their services to the public writ large. Nor do we think that such providers would normally be described as aiding and abetting, for example, illegal drug deals brokered over cell phones—even if the provider’s conference-call or video-call features made the sale easier. . . .

In this case . . . there is no allegation that the platforms here do more than transmit information by billions of people, most of whom use the platforms for interactions that once took place via mail, on the phone, or in public areas. The fact that some bad actors took advantage of these platforms is insufficient to state a claim that defendants knowingly gave substantial assistance and thereby aided and abetted those wrongdoers’ acts. And that is particularly true because a contrary holding would effectively hold any sort of communication provider liable for any sort of wrongdoing merely for knowing that the wrongdoers were using its services and failing to stop them. That conclusion would run roughshod over the typical limits on tort liability and take aiding and abetting far beyond its essential culpability moorings.

Thomas did warn, however, that this standard did not preclude liability in all cases:

There may be, for example, situations where the provider of routine services does so in an unusual way or provides such dangerous wares that selling those goods to a terrorist group could constitute aiding and abetting a foreseeable terror attack. Cf. Direct Sales Co. v. United States, 319 U. S. 703, 707, 711–712, 714–715 (1943) (registered morphine distributor could be liable as a co-conspirator of an illicit operation to which it mailed morphine far in excess of normal amounts). Or, if a platform consciously and selectively chose to promote content provided by a particular terrorist group, perhaps it could be said to have culpably assisted the terrorist group.

Every justice joined this opinion; only Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson wrote briefly to caution that the general principles applied in Taamneh might “necessarily translate to other contexts” under other aiding-and-abetting statutes.

Section 230 Goes Untouched

Having rejected the main theory of liability under JASTA, the Court brushed off Gonzalez, issuing a unanimous, unsigned per curiam opinion finding that the same theory of liability wouldn’t fly in that case — a point the plaintiffs conceded — and sending the case back to the Ninth Circuit to see if there was any other argument the plaintiffs could make to salvage their case. Thus, any prospect of a direct ruling on the scope of Section 230 will have to await another day.

That day is fast approaching in the context of Section 230’s rules on social-media-platform immunity from liability for banning or moderating content. States such as Florida and Texas are pushing the limits of when states can hold the platforms liable for what they ban, not what they decline to ban.

Nonetheless, Taamneh offers some lessons. The normal common-law rules still work perfectly well in most situations. If Congress or state legislatures want different rules specific to social-media platforms, they will need to get into the weeds of writing them in detail themselves. They might find that there is wisdom, instead, in the time-tested traditions of the common law.