For years, Aurora residents have heard the allegations of violence and criminality by some members of the Colorado city’s police force: officers punching, choking, and threatening to shoot unarmed civilians; holding innocent people at gunpoint; stalking and sexually assaulting people.

In 2018, a man died after Aurora officers punched and pummeled him with batons and shocked him more than a dozen times with stun guns. A year later, an on-duty officer with a blood-alcohol level more than five times the legal limit passed out while driving. He wasn’t fired, arrested, or charged with a crime, and was later promoted.

In 2019, Aurora became a national flashpoint after officers restrained and choked Elijah McClain because someone reported that the young black man “looked sketchy” while walking home from a convenience store. The 23-year-old died after medics injected him with a lethal dose of ketamine, a powerful sedative. Soon after, some officers returned to the scene and snapped photos of themselves grinning in a mock chokehold in front of a memorial to McClain.

An investigation by the state’s attorney general found Aurora officers engaged in a consistent pattern of illegal behavior, racially biased policing, and use of excessive force. The attorney general is now overseeing mandated reforms to the embattled department.

It was in this atmosphere that Aurora’s Civil Service Commission in December chose to rework its qualifications to be a police officer in the city. Considering the community’s distrust of the embattled police force, tightening up the department’s minimum standards to ensure that only the best and brightest applicants would be considered may have seemed like a commonsense move. But that’s not what the commission did. Rather than tighten the minimum qualifications to be a police officer in Aurora, the commission relaxed them.

According to the reworked entry-level qualifications, Aurora police candidates who have committed two or more misdemeanor crimes are no longer automatically disqualified from joining the force. They also won’t be automatically disqualified if they have a large number of driving offenses, or if they’ve recently had a DUI, had their driver’s license suspended, or used illegal drugs.

In Aurora, not even a history of “dishonesty and/or integrity issues,” or falsifying or making misleading or deceitful statements on a job application, is enough to automatically disqualify a candidate for a job as a police officer.

That relaxing of standards, particularly around honesty and integrity, was a step too far for Lindsay Minter, a local activist who served on a now-disbanded citizen’s committee for policing.

“That being loosened up was just, like, astonishing to me, because we already have problems with integrity in the police force,” she told National Review. “If you uphold your standards, you’re going to get the people who want to do their job and want to do the job correctly. Lowering standards is not going to get more quality applicants.”

Aurora is far from the only police force that has changed, relaxed, or lowered its minimum qualifications in recent years. As interest in policing careers has plummeted — and as departments seek to open their doors to more females and minority officers — agencies nationwide are eliminating college requirements, lowering fitness standards, and relaxing policies around tattoos and past drug use to bolster their recruiting numbers. The reduction in standards seems to fly in the face of calls to improve policing in the United States.

In recent years, police departments in cities like Chicago, Philadelphia, New Orleans, Pittsburgh, Louisville, Ky., Boise, Idaho, and Portland, Ore., have all lowered or relaxed requirements that recruits have at least some college credits before joining the force. The New York Police Department recently scrapped a timed mile-and-a-half run to help more women qualify for the force, and because, as training chief Juanita Holmes told the New York Post, “no cop on patrol runs a mile and a half. No one’s chasing anyone a mile and a half.”

It’s a troubling trend for many pro-police advocates, who worry that lower standards will lead to the hiring of more problematic cops, who will then hurt people and make more mistakes, turning more people against police and further demoralizing the profession.

“I’m gravely concerned about this,” said Jason Johnson, president of the Law Enforcement Legal Defense Fund, a nonprofit that supports officers wrongly charged with crimes and that advocates for sound and professional policing.

“It’s almost as if we are seeking what the activists have most complained about,” Johnson said. “They’ve accused law enforcement of all sorts of things that I think mostly are completely false, not true, that cops are racist, brutal, horrible people with terrible backgrounds that are ignorant and uneducated liars. And it’s almost like we are now hoping to actually fulfill that prophesy by the direction that we’re heading.”

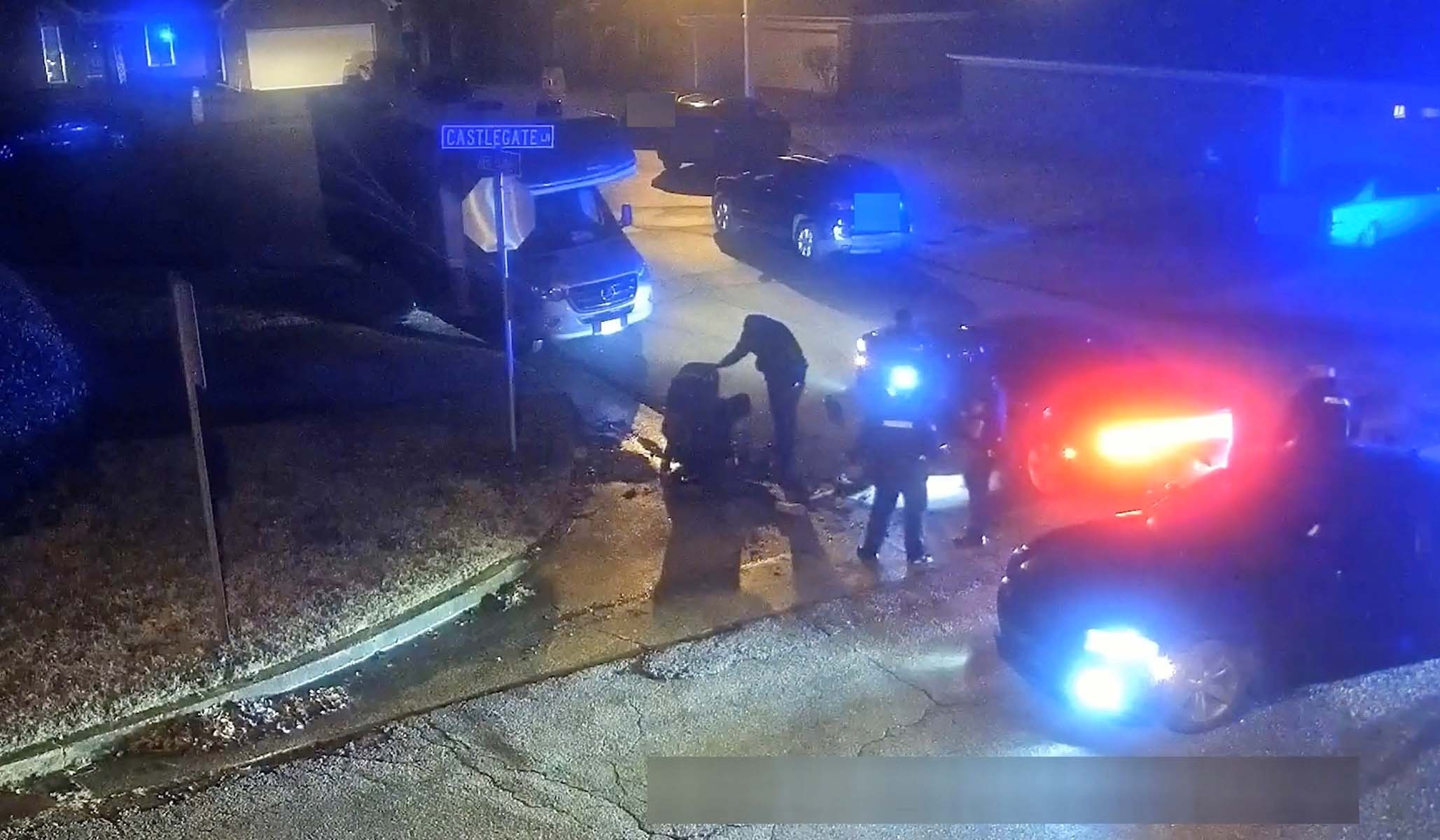

On January 10, just a few weeks after police qualifications were relaxed in Aurora, and a thousand miles to the east, five officers beat Tyre Nichols to death in Memphis, Tenn. Two of those officers were hired after department leaders, desperate for recruits, pumped up signing bonuses, sought waivers for candidates with criminal records, and phased out requirements that recruits have either college credits, military service, or previous policing experience. One of the officers accused of beating Nichols to death, Demetrius Haley, had previously been sued for beating an inmate while he was working as a corrections officer.

“They would allow just pretty much anybody to be a police officer,” Alvin Davis, a retired Memphis police recruiting lieutenant, told the Associated Press. “They’re not ready for it.”

Desmond McNeal, chair of the Aurora Civil Service Commission, told National Review that commissioners relaxed their police qualifications as part of an effort to “look at the whole person in the hiring process,” because “you can’t summarize somebody necessarily based off one incident.” Many automatic disqualifiers from the past are now just potential disqualifiers in Aurora. McNeal said the idea is to allow otherwise good candidates to move forward in the hiring process even if they’ve made some mistakes in the past. In some cases, he said, good candidates have been disqualified for making honest mistakes on their job applications, including leaving off pertinent information about their past.

“We’re saying, let’s look at this person as a whole,” McNeal said. “Did this person mess up their paperwork, or are they a liar, are they trying to hide something?”

McNeal said there is always a concern that officers they hire could step over the line, leading to another Tyre Nichols, Elijah McClain, or George Floyd incident. But he believes the reworked standards will allow the department to differentiate habitually dishonest applicants from those who have simply made a mistake. He doesn’t believe the standards are lower now.

“I just feel like it is adjusting the standard to try to meet the challenges that the country faces, which is, it’s a police shortage everywhere,” he said. “Nobody wants to be a cop right now.”

Recipe for Disaster?

While reports of veteran officers fleeing the police profession increased after George Floyd’s killing in Minneapolis in 2020 — and after the subsequent riots and the emergence of the defund the police movement — departments had been struggling with recruiting for years.

The New Orleans Police Department dropped its requirement that recruits have at least 60 hours of college credit in 2015, just four years after the college-credit policy was put in place. To increase application numbers and to increase diversity, the Philadelphia Police Department scrapped its college requirement in 2016.

“We want the community and the police department to reflect what we have here demographically,” Sergeant Robert Ryan told CBS News at the time. “We are working with different communities to sort of get the word out there to say, ‘we want you to join.’”

Former Philadelphia Police Commissioner Charles Ramsey defended the college requirement.

“I think we do a disservice to young people by having them go through school thinking they can get good-paying jobs without at least looking at some level of college work,” he told the Philadelphia Inquirer. “I also think it’s an embarrassment to think that you have to lower the standards.”

The Louisville Metro Police also ended its college requirement in 2016, according to news reports. The Portland Police Bureau scrapped its college requirement in 2019. The police departments in Chicago and Pittsburgh relaxed their college requirements in 2022.

The Houston Police Department no longer requires applicants to have college credits, or military service or previous policing experience, said Kristine Anthony-Miller, the department’s recruiting commander. In 2018, she said, the department “expanded” eligibility to include applicants who have had any full-time employment for 36 of the past 48 months.

“It really brought in more applicants who just work hard and have a great work ethic, and we’re seeing great returns on that,” Anthony-Miller told National Review.

But Jeff Hynes, a former Phoenix police commander involved in hiring and training, said that lowering police education standards is a “recipe for disaster.” Hynes, who now teaches in the Justice Studies program at Glenndale Community College in Arizona, said better-educated police officers tend to have broader worldviews, and more maturity and cultural awareness.

Research over the last couple of decades has found that college-educated police officers are significantly less likely to use force on the job, are less likely to fire their weapons in the line of duty, assault citizens, or lose their jobs due to misconduct, and they get fewer citizen complaints.

“Education and standards make better cops, period,” said Hynes, who added that he doesn’t care what a prospective recruit’s college degree is in.

“With all of the complexities of policing and understanding the law and writing and judgment, it just seems to me you should have more than a high school education to be a police officer today,” Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, told National Review. “Two years to me seems to be a minimum, and departments are dropping that.”

‘An Erosion of Standards’

In addition to lowering education qualifications, some law-enforcement agencies have relaxed other standards to encourage more applicants and to diversify their forces.

For example, in Asheville, N.C., the department now allows officers to live as far as 45 miles away from the city, up from 30 miles previously, a spokeswoman said.

In 2017, Baltimore’s police commissioner pushed for the state to ease restrictions on past marijuana use, which it ultimately did. Louisville also has eased restrictions on prior drug use.

Several law enforcement agencies — including the police departments in places such as Springfield, Mo., Middletown, Ohio, and Lakeland, Fla. — have loosened policies that previously prohibited officers from having visible tattoos.

In 2015, the North Miami Police Department dropped a swim test because too many black applicants couldn’t pass it. In Madison, Wis., the police department replaced a bench-press requirement with pushups as a measurement of upper-body strength so more women would pass the fitness test.

The Madison case was noted in “Advancing Diversity in Law Enforcement,” a joint 2016 report by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division and the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission that urged agencies to eliminate barriers to hiring officers who “reflect the diversity of the communities they serve.”

Law-enforcement advocates who spoke to National Review were open to several of the changes in standards that departments have been making. Relaxing restrictions on tattoos, for example, likely won’t have much of an effect on on-the-ground policing, Johnson said, though he still has reservations.

“I think it’s a symptom of an erosion of standards,” he said. “We’re now following the rest of society down into this anything-goes mentality.”

When it comes to relaxing prior drug-use limits, Johnson said the “devil is in the details,” noting that some departments have tight caps on lifetime marijuana use. In some cases, he said, military veterans who served with distinction could be prohibited from becoming police officers because they smoked pot too many times in college.

“That’s just silly, and that should be eliminated,” Johnson said.

Wexler said he is open to reworking or loosening some fitness requirements, which disproportionately lead to more female applicants missing the cut. Law-enforcement leaders love hiring female officers, who tend to be involved in fewer shootings and use-of-force cases.

“Of all the skills that police officers need, I would put physical fitness after judgment and discretion and intelligence and writing and decision-making,” Wexler said. “I would not compromise on anything that has to do with character.”

Anthony-Miller with the Houston Police Department said her department has had some challenges with recruits struggling with physical-fitness requirements. They have reduced some requirements to get people into the academy, and then they work from there to get them up to the department’s standards.

“A lot of young people growing up, they’re on social media, they’re on their phone, they’re on Playstation, Xbox,” she said. “I don’t know if there’s been an emphasis on physical fitness.”

Johnson said he’s open to law-enforcement agencies changing some exercises and replacing them with others, as long as the officers being hired are fit and healthy. But he worries that departments are intentionally watering down requirements just to get the limited number of recruits they have over the hump.

“The job actually requires physical fitness to do it properly,” he said.

‘This Is Not a Numbers Game’

Not all law-enforcement agencies are lowering hiring standards. Several of the agencies that National Review reached out to — including the Dallas Police Department, the Colorado Springs Police Department, and the Eau Claire Police Department in Wisconsin — said they have not changed their hiring qualifications or standards in recent years. Leaders with both the Atlanta and Seattle police departments have publicly denied that they’ve lowered hiring standards.

“SPD won’t hire just anyone,” Seattle’s then-interim chief Adrian Diaz told an NBC affiliate in July. “Despite our current staffing crisis, this is not a numbers game. Our mission is simply to help people, so we will hire only the most compassionate, dedicated, and qualified employees.”

Hynes, the former Phoenix hiring and training officer, urges departments to hold their ground, to fill their ranks with their best A-level and B-level recruits, and to treat their officers well. Departments should resist the urge to dip into hiring pools that include young and inexperienced applicants without at least some college education, he said.

“That will equal increased use of force, increase of brutality, increase of mistakes, increase of hiring officers that are not reflective of the communities they serve,” Hynes said.

Johnson said there needs to be a concerted effort across the board to recast law enforcement and repair its damaged reputation.

“Elected leaders have to stop diminishing the importance of law enforcement, have to start giving the profession greater respect, and actually try to attract the best and the brightest to serve their communities,” he said. “I think that when the profession is denigrated and is talked about as if police are just a bunch of racist thugs, then that really dissuades the best and the brightest. They don’t want to be part of that.”