NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE L ast week I wrote about the spicy Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. I’d never been there, I’m ashamed to say, but we can’t be everywhere, and I made amends with a nice, long visit to this bustling, cultured city and a half dozen of its museums. I was delighted to see the art museum’s Joan Brown exhibition, delighted and electrified.

Brown (1938–1990) is hard to classify, which defines and commends her. She is from San Francisco and has danced to the beat of her own drummer in the best — not worst — Bay Area tradition. No surfeit of Twinkies or toxic Kool-Aid in her world. Her idiosyncratic subjects, bright, snazzy colors, and copious patterns, mostly in paintings but sometimes in sculpture, put her in no school except one for eccentrics such as Wayne Thiebaud, Bob Arneson, and Jay DeFeo. She’s seriously whimsical and whimsically serious.

Brown is fearless, too. The Carnegie’s exhibition, aptly called “Joan Brown” since her art defies words, is a wonderful survey. Good for this high-spirited, creative museum. Brown’s well known in kooky, zesty San Francisco but unknown in Pittsburgh. And, yes, there’s even a swami in her life.

In the late ’50s, as a teenager who liked to paint and didn’t want to go to an academic college but otherwise lacked a rudder, Brown entered the California School of Fine Arts, later the San Francisco Art Institute. She had two giants among art teachers. Elmer Bischoff and Richard Diebenkorn started their own careers steeped in Abstract Expressionism but, over time, moved toward figures and cityscapes. Bischoff told a colleague that Brown was “an extraordinary student” and “either a genius or very simple.” Like the best art teachers, Bischoff and Diebenkorn taught Brown, above all else, to trust her instincts.

That she did. By 1960, Brown found a distinctive, many-sided vision. Her surfaces were dense with paint. Her palette is saturated and bold. She became a mother in 1962. Many of her paintings in the ’60s depict her new son, dressed as a leopard for Halloween or sitting in front of a Christmas tree. She learned to love swimming at San Francisco’s beaches and claimed that the water was uniquely healthful. In Girls in the Surf with Moon Casting a Shadow, from 1962, her surf looks like surf, created as it is from splattered paint. Her figures have campy, charming faces, with bulbous noses, bug eyes, and arbitrary, oddball colors.

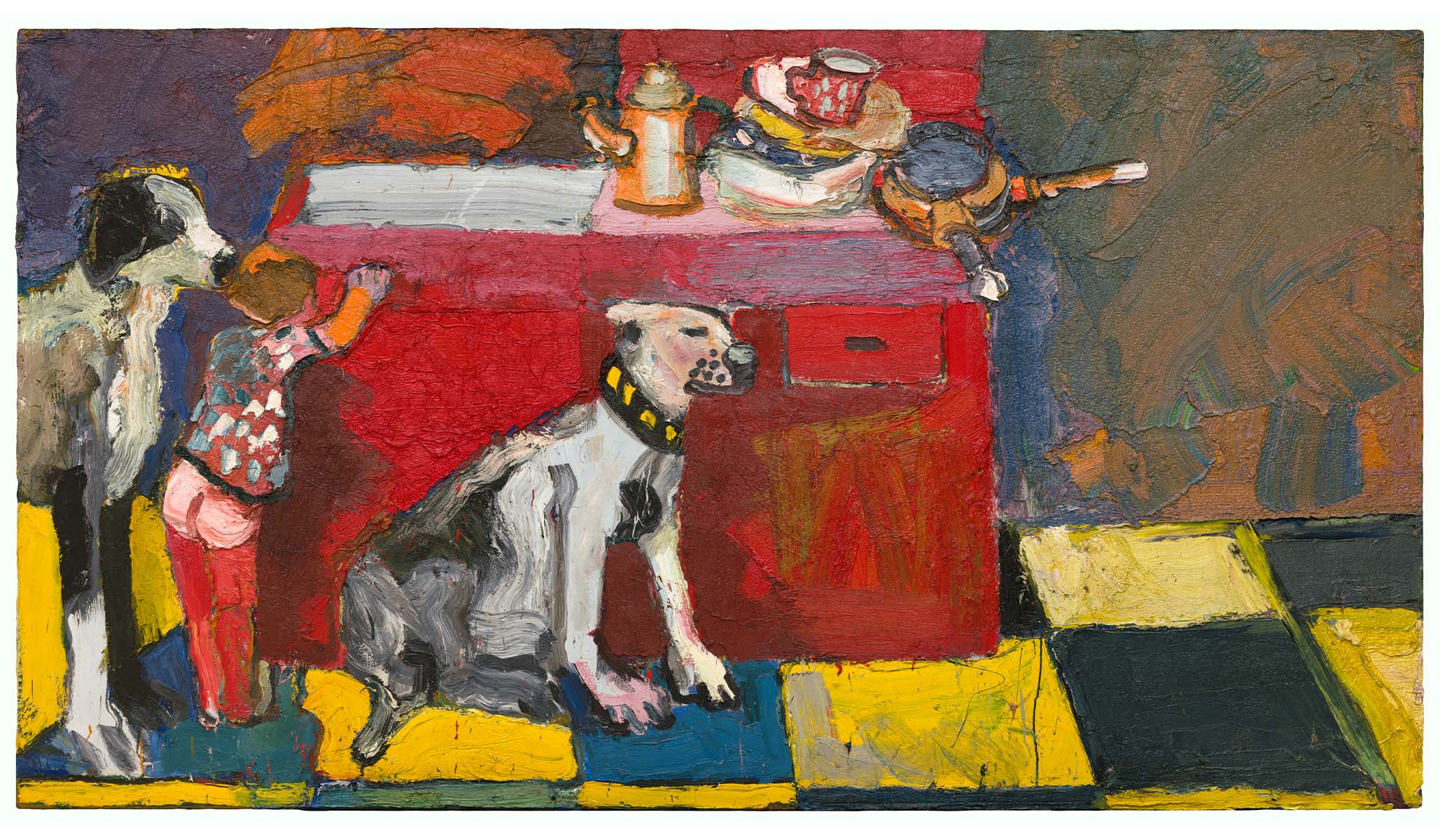

Brown’s pets often have starring roles. Noel in the Kitchen, from 1964, puts her dog, Bob, front and center. Noel, her son, is in the painting, too, his bare baby butt facing us. Bob has the essence of doghood. To paraphrase Rogers and Hammerstein, he enjoys being a dog.

A savant, Brown had her work exhibited in the 1960 Whitney Biennial, then an annual event. Trusting her instincts made her a niche star. The art world then was a rough place for women.

For someone who’d never been to the Met, much less Europe, until she was in her late 20s, Brown is passionate about Old Master painting. In piquant riffs, she quotes Annibale Carracci, Goya, Rembrandt, Velázquez, and many others in the art-history canon. Almost all truly good artists look closely at the Old Masters, the Romantics, and the Impressionists, even if historians of contemporary art don’t know much of anything about them, which is almost always the case.

Joan Brown is chronological, which matters since her style and subjects abruptly shift. In the late ’60s, her handling of paint changes. Her surfaces flatten, which gives her figures, colors, and patterns more resolution. It’s the era of Pop Art, and while Brown is by no means a Pop artist, pictures such as Gordon, Joan, and Rufus in Front of SF Opera House, from 1969, have the whiff of a cartoon and a deadpan look. I thought of Alex Katz but would call Katz wistful, not whimsical. Brown had four husbands. Her family’s a staple in her work, so the men come and go. Gordon, for instance, was husband No. 3. Brown’s first three husbands were artists. No. 4 was a cop. She’s willing to experiment in art and love.

Brown’s depictions of animals change, too. She adds a buffalo and a wolf to her repertoire, obviously not pets, as well as cats, birds, and fish painted to look hieratic. The Bride, from 1970, probably Brown’s best-known painting, depicts a standing cat dressed in an old-fashioned ruffled wedding dress standing in a field of flowers against a blue sky with floating fish instead of puffy clouds. The cat bride holds a leash tied to a badger. Yes, they’re weird, and, yes, they made me think of the French Symbolist Henri Rousseau, another old artist Brown admired, and, yes, her animals turn spiritual — King Tut’s–tomb spiritual.

Her patterns, whether fields of flowers or checkered floors, remind me of the Pattern and Decoration Movement, which started in the late ’60s and ran through the early 8’80s. I’ve written about Pattern and Decoration art before. It’s one of the last art movements in America with cohesion and the feel and look of a rebellion.

Brown did around 400 paintings in her career. A hundred of them are self-portraits, nearly all done starting in the late ’60s. They range in size from bigger-than-life and cryptic to 20-by-15-inch face shots depicting Brown drinking tea or wearing different hats. Brown had a pretty, round face and big, riveting, robin’s-egg-blue eyes. Most of her work is big, so her pictures often look like altarpieces, with her figure a totem pole or a brightly colored silhouette. Brown did the annual Alcatraz Swim. The Night Before the Alcatraz Swim, from 1975, and After the Alcatraz Swim #3, from 1976, are indoor/outdoor pictures. The indoor scene places Brown in a bright interior. Through a window is a nocturne, a picture within a picture, of Alcatraz surrounded by water, in the early scene calm, after the swim roiled.

Sometimes her distorted early-’60s faces return. At the Beach, from 1973, is one of my favorite paintings in the show. It depicts four women with faces that could have come from a picture by James Ensor. Each holds a glass of red wine, likely not her first. Skin color ranges from periwinkle to orange to dark pink. Next to the women is an empty outline of a male swimmer. It’s bizarre.

Brown’s work in the ’80s is bewitching. She travelled more, going to India and Egypt, and became involved spiritually with the yogic guru Swami Kriyananda in San Francisco and Sathya Sai Baba in Bangalore. Being a devout Methodist from Vermont, I can’t say that I naturally understand their appeal, but Brown’s paintings from the ’80s, what she called her Energy Field work, is again very different from what came before. Her palette turns pastel, her surface patterns less exacting and defined and more like Vuillard’s. Her figures are ethereal.

Brown died suddenly and tragically in 1990 in India. She was painting in a studio that Sai Baba had equipped for her when a concrete turret in Baba’s building collapsed, crushing her. Her work in the late ’80s is spiritual and ecumenical.

She painted a series of Franciscan subjects. She seems to have become interested in astrology. She explores dualities in self-portraits of her as half human, half cat, or with Egyptian or Mayan divinities by her side.

Brown’s work in the ’70s and ’80s wasn’t always received with roses from art critics. In the ’70s, abstraction still ruled the critical roost. New York critics often viewed artists from San Francisco and Los Angeles with contempt. These artists were provincials, critics suggested, with a whiff of envy given New York’s disgusting, messy winters and hot, muggy summers. After her death, her reputation receded to the realm of Bay Area art connoisseurs before things there went crazy.

In the ’80s, the New York art dealer Allan Stone, whose biography I’m writing, became smitten with Brown’s work and sold a lot of it. In the mid ’80s, Allan spent a few months each year in San Francisco. He’d discovered Wayne Thiebaud in 1962, so he had a long-standing relationship there. He loved the eccentricity and the aversion to pomp and cant that he saw in San Francisco artists. Their work seemed the antithesis to what was happening in New York. There, the art world could be ponderous as well as more about money than art.

I have a few quibbles with Joan Brown. The exhibition has a little more than 40 paintings and sculptures, so it’s medium-size. Reading the catalogue, produced by SFMoMA, I saw illustrations of many fantastic things that didn’t make it to Pittsburgh. Galleries are what they are, but the Pittsburgh iteration missed a chance to do Brown big. I wished her ’80s spiritual pictures got more context. Brown had a serious, successful career lasting 30 years. A third of this period involved her immersion in Eastern religion. Brown’s deep knowledge of art history also needed a close look. Her tastes were catholic, and her talents were suited to taking the work of the Old Masters especially and interpreting it in a way that was uniquely hers.

Brown’s a delightful sculptor. I wish more was done with it. Luxury Liner, from 1973, is so fun. I’ve already compared Brown to Alex Katz. Katz’s cutout sculptures are among his very best work. Brown’s a better artist than Katz, more daring and original, so I can’t say her sculptures, among them cutouts, are stronger than her paintings. They needed more of a place in the sun.

The catalogue’s a fine book. It’s sumptuously illustrated. The first 200 or so pages are illustrations and a handful of one- or two-page essays and lots of insightful quotes by artists and critics describing what, say, a Brown painting, meant to them. Long, meaty essays on Brown and Western art, her self-portraits, and her New Age spirituality are at the very end. I would have placed these essays in intervals earlier in the book. They’re well done and enlightening, so they needed to be mixed with the catalogue’s high-quality illustrations.

In 1983, Brown wrote an essay in which she asked, “Why can’t art historians and critics learn the difference between knowing and knowing about?” A very good question. It’s the difference between objectivity and subjectivity, and art historians are, after all, historians. Critics by necessity need to keep some distance between their subjects and themselves, though a good critic’s passion for art and art’s intrigues should always shine. Good critics and good artists are tuned to what’s universal. And to a sense of the world as a work in progress and a place of possibility. Good artists go with their instincts. That’s hard to decipher, and artists like to keep things mysterious.

I loved Old Paint Shoe, New Paint Shoe, from 1972. It’s a painting of two shoes. The white shoe on the left is new to the job, just from the factory and rigid, with a smidgen of red paint. It’s got the look of promise and that first-day-of-school crispness. The shoe on the right has the look of experience, of accomplishment, comfort, and confidence. It has stretched as the artist has moved and pivoted. Brown’s a fine artist for many reasons, but most appealing to me are her love for new beginnings, a passion for growth, and her courage to experiment. Joan Brown conveys this beautifully, so I consider the show an inspiring success.