The recording industry’s recent celebration of hip-hop music’s 50th anniversary coincided with the Democratic Party’s appropriation of black political history. The Grammy Awards’ chaotic, splintered tribute included one surviving member of the trio De La Soul, and later that month Joe Biden marched with Al Sharpton and other race hustlers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge at a commemoration in Selma, Ala. Both stunts co-opted American culture.

But then — amazingly — De La Soul’s long-unavailable music catalog appeared for the first time on global streaming services, an occasion that rectifies the terrible expropriation of art by politics.

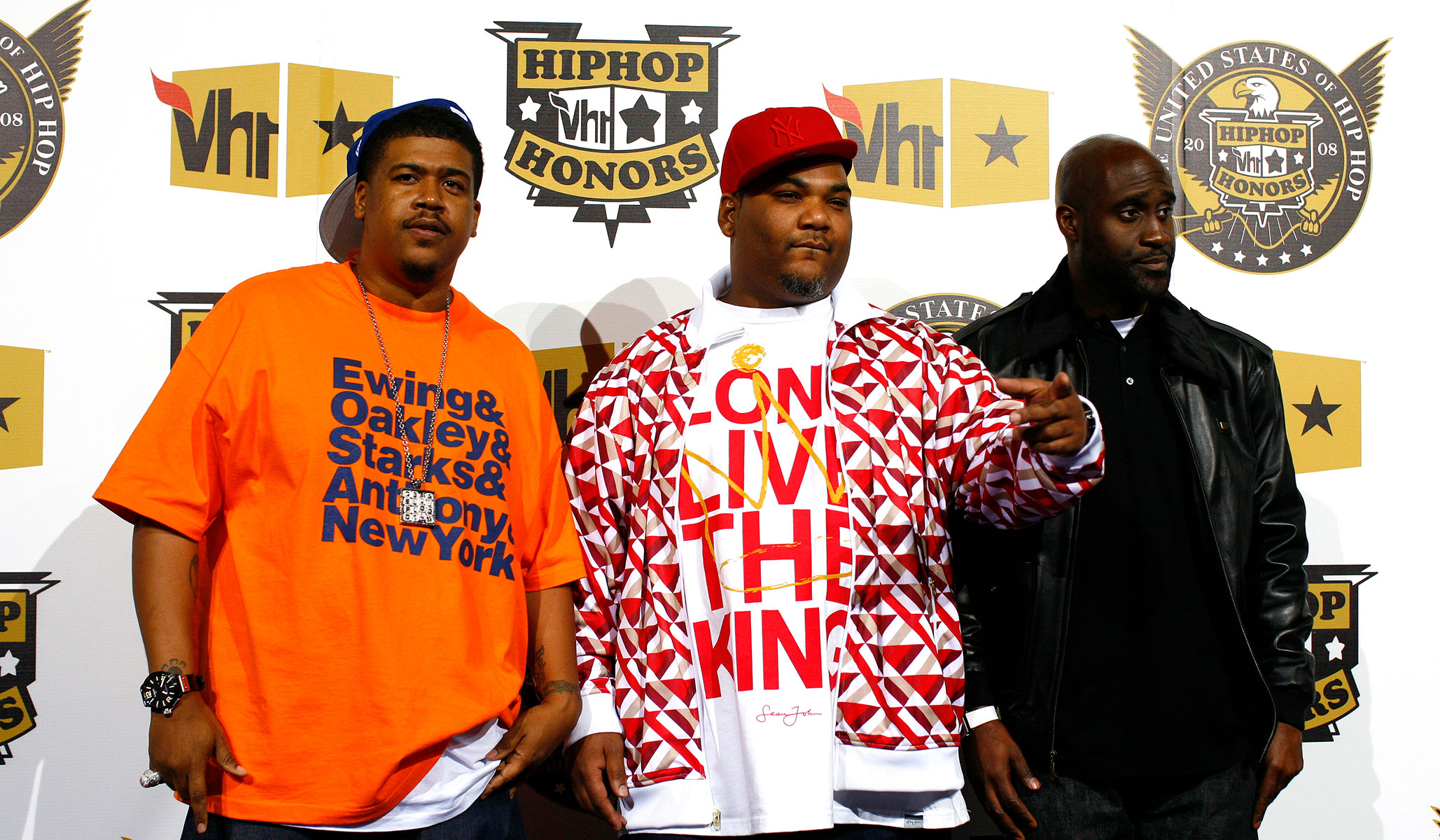

De La Soul’s originality — especially the group’s first two albums, 3 Feet High and Rising (1989) and De La Soul Is Dead (1991) — still feels irrepressible. It refuses all hip-hop clichés; in fact, the rappers Posdnuos (Kelvin Mercer), Trugoy (David Jude Jolicoeur, recently deceased), and the DJ Maseo (Vincent Lamont Mason Jr.) opposed urban-ghetto stereotypes yet made some of the most pleasurable and thought-tickling records of hip-hop’s peak, in the late ’80s and early ’90s.

Producer Prince Paul (Paul Edward Huston) sampled eclectic musical history — from Liberace to Steely Dan — for the group’s personal, poetic collages. As with the astonishing advent of Motown in the Sixties, De La Soul weren’t afraid to show that they knew almost as much about American culture and language as Berry Gordy (while their peers Public Enemy added what they knew about black political militancy and their other peers, Run-DMC, showed what they knew about being mannish). The group’s name meant “from the soul,” the source of their sincere, cheerful access to Western Civ. These savvy youths from Amityville, Long Island, confounded the expectations of anyone who heard them.

Conservatives should know De La Soul for daring to acknowledge Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” anti-drug campaign in their masterpiece “Say No Go.” Not so much a partisan tribute, its response to the freebased crack-cocaine crisis in the ’80s that was devastating urban communities in tenements, alleys, and parks exhibited genuine black conservatism:

Now, I never fancied Nancy

But the statement she made

Held a plate of weight

I even stressed it to Wade

Did he take any heed?

No, the boy was hooked

You could phrase the word “base”

And the kid just shook.

That one-word rhyme (“shook”) conveyed the neurological injury of the crack epidemic. De La Soul broke from the black urban Democratic Party pack to show how powerful — and ingenious — hip-hop can be. Such a pop group could exist only when intellectual independence was prized by thirsty record companies, an enthralled public, and an open-minded media. (3 Feet High and Rising commanded 1990 music polls.) De La Soul’s poetic flourishing of language contrasts with today’s inane repetition of pseudo-enlightened slogans like the “diversity, equity, and inclusion” mantra robotically parroted by dancer Misty Copeland.

De La Soul cherished its individuality. On “Me, Myself and I,” they rap about self-confidence, bonding into Emerson’s majority of One: “Style is surely our own thing / Not the false disguise of showbiz.” That also describes their suburban-street politics, buoyed by George Clinton’s funk-music bounce. Hyped as bringing back flower-power hippiedom through the “D.A.I.S.Y. Age,” De La Soul, instead, translated the acronym as “DA Inner Sound Y’all.”

Black self-expression has been ruthlessly usurped during the Biden administration, but De La Soul’s revival maintains the complex self-awareness (and ingenuity) that no demagogue can expropriate.

On “Eye Know,” De La Soul raps, “Hold my hand and we’ll pick my plantation of daisies for a bouquet of soul,” reversing Biden’s cheap, patronizing Good Ol’ Boy bait, shouted to a black audience: “They gonna put y’all back in chains!”

De La Soul also transcends rap’s current porno vulgarity. “What’s More” (from the B side of “Me, Myself and I”) asks, “What’s more old-fashioned: Lemonade, a black man’s fade [haircut], or a kiss that’s soaked in passion?” Not merely erotic, such deep joy feels like skipping rope. (The memory of seeing Posdnuos ride a tricycle on stage at the Beacon Theater in 1990 remains a delightful shock.)

At first, I was skeptical about De La Soul’s new prominence, then, while shopping, I realized the significance of their revival, as I heard them piped in, streaming back to back in a perfect lineup with Roxy Music’s “Virginia Plain” and the Beatles’ “I Get By with a Little Help from My Friends.” De La Soul’s experimental hip-hop, now available again, sounded equally liberating, a reminder of the ingenuity that political marauders try to expropriate from black culture.