NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE B arring some exogenous shock to our economy, we are about two months away from having functionally solved the latest round of inflation. This is not some brilliant piece of prophecy — nor is it unmitigated good news. It is merely an observation about something that has already occurred, but that is widely misunderstood. The headline CPI data, the main reported figure, is only catching up with the reality. Tuesday’s 4 percent year-over-year figure masks the true current inflation figure, which is much lower and declining.

David Bahnsen and Lacy Hunt have been shouting this from the rooftops for months now, but the message does not seem to have penetrated the Fed. This misapprehension will inevitably lead to policy mistakes, as overly zealous inflation warriors seek to keep the rate hikes coming.

Those of us in the real-estate sector have noticed the flattening — and in some submarkets the outright decline — of rents across the country, often in the markets that were the hottest during the mania of 2021–2022. Nevertheless, “shelter” remains an active component in the headline CPI number, with the shelter CPI measure continuing its rapid increase despite the contrary worry from every industry professional you will speak to:

This graph, which shows that the cost of shelter is rapidly increasing, is a distortion of our current reality. The cost of shelter is not, in the main, increasing at all. And it is certainly not increasing at an accelerating rate. The problem, however, as I discuss below, is that cost of shelter is a lagging indicator.

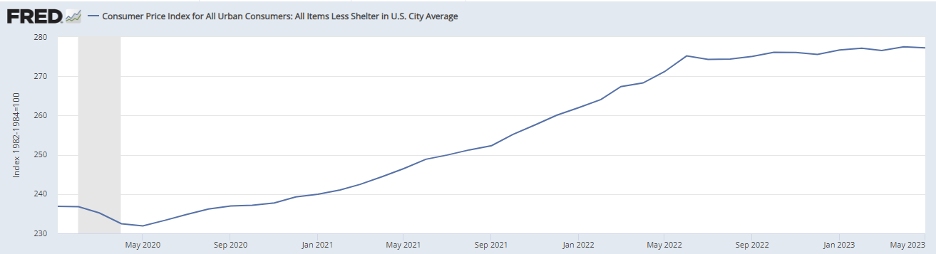

At the risk of oversimplification (price levels for different products do not fluctuate in unison), there is another graph, one that highlights our true current low-inflation environment: CPI Less Shelter. This metric is exactly what it sounds like: the Consumer Price Index measurement with the (above-shown) cost of shelter stripped out. This measures price increases in everything in the CPI’s basket of goods besides housing:

The truth is, as clearly demonstrated by this graph, that the rate of inflation hit a wall one year ago, in June of 2022, when the CPI Less Shelter was 275.182.

The most current available number is the May 2023 number, eleven months later: 277.228, or just 0.07 percent above June 2022.

Compare this to the number in July 2021, eleven months prior to June 2022, and the inflation-rate, less-shelter increase was 10.1 percent. This means, happily, that the most painful upward price shocks are now firmly behind us — and have been for some time.

Why, then, do we still see a 4 percent year-over-year number in the headline CPI that misleads so many? The conclusion is simple: Outdated cost-of-housing data (a quirk of the methodology of measuring this number via “Owners’ Equivalent Rent”) is disguising the true inflation rate. When we finally have the June 2023 numbers in a couple of months, the (outdated but less outdated) shelter costs will begin to reflect the flattening trend already observed in this area. This flattening will be more reflected into the headline CPI, and inflation will vanish as a political concern.

At that point, the public can shift its focus to dealing with more pressing economic issues. Unfortunately, we have yet to fully deal with the consequences of having built up indebtedness to a very high level during the era of ultra-low rates and then following it with a rapid-rise rate policy. The pain will be substantial, but we have a small opportunity now to change course and avoid adding unnecessarily to the economic hardship to come.

The responsible thing for policy-makers at this point, then, is to begin the pivot away from monetary tightening, and explicitly orient policy toward economic growth (the false choice between these two options is not my framework, but it appears to be the Fed’s, and other devotees of the Phillips curve). Inflation is now yesterday’s concern.

This means that, at the very least, a pause in rate hikes is prudent. The rates already in place are more than sufficient to continue reducing the money supply, as lower-interest loans mature and roll over into higher-rate loans, and banks tend to lend less.

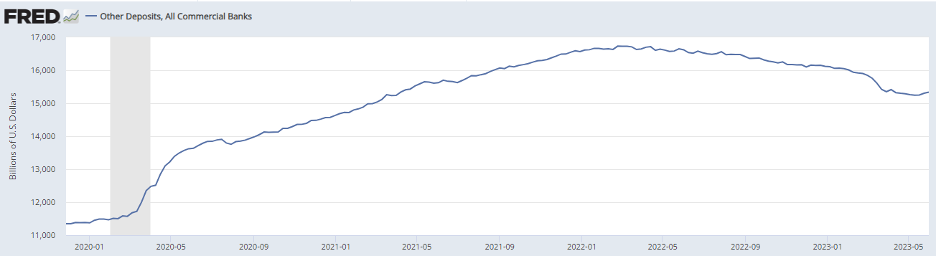

We can see this effect has already taken root. Other deposits of commercial banks, the most active component of the money supply, have declined by almost $1.5 trillion since their peak in February 2022, from $16,731.4 billion down to $15,338.32 billion, a decrease of 9.1 percent:

While this number is large in absolute terms, it is still declining, even at the current Federal Funds Rate of 5.06 percent, as it was declining when the rate was at 4 percent, and 3 percent.

On that basis, I’d argue that suggesting, as Kevin Hassett did the other day on Capital Matters, that the Central Bank take more account of the Taylor Rule (essentially, setting rates two percentage points above the inflation rate) is unnecessary.

Looking forward, do not be surprised as inflation comes down over the next few months — the truth is, it is already down now. The time has come to worry about the next difficult chapter of this economic cycle: the pain of low or negative growth and its unhappy derivative effects. Mitigating that pain should now be priority number one.

The Fed often touts its “data-driven” approach. However, if the data are obsolete (as they are in the shelter measure), the Fed will forever be reacting to last month’s economy. In this fast-moving situation, it is time for the Fed to look forward and end the rate-hiking cycle.

Broadly speaking, price stability has been achieved. That job, at least, is done.