The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Poems, Volume 1: 1927–1939, edited by Edward Mendelson (Princeton University Press, 848 pp., $60)

The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Poems, Volume 2: 1940–1973, edited by Edward Mendelson (Princeton University Press, 1,120 pp., $60)

NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE I n 1939 a Kansas City rabbi, Harry H. Mayer, commissioned poets to write their own “versions” of the psalms for a forthcoming anthology, The Lyric Psalter. Mayer assigned Psalm 27 to W. H. Auden. His verse glorifies God but brings the divine down to earth. “Our flesh is silly and afraid,” the narrator concedes. “Give out Thy secret,” he says, and “teach us how / Thy public may grow loving now.” In Auden’s vision, God is still magnanimous and magnificent, but the speaker’s focus is on the “enfeebled and unfed.” We need a God, Auden suggests, who would dare to love us.

Auden’s inclusion in the anthology was fortuitous. Around the time he composed the poem, he went to the 86th Street Garden Theatre in Yorkville, on the East Side of Manhattan. His curiosity piqued by a provocative review of the film Das Ekel (The Pain in the Neck) and an accompanying German newsreel, Auden found his worst fears realized: “Quite ordinary, supposedly harmless Germans in the audience were shouting ‘Kill the Poles,’” he later remarked. “I wondered, then, why I reacted as I did against this denial of every humanistic value. The answer brought me back to the church.”

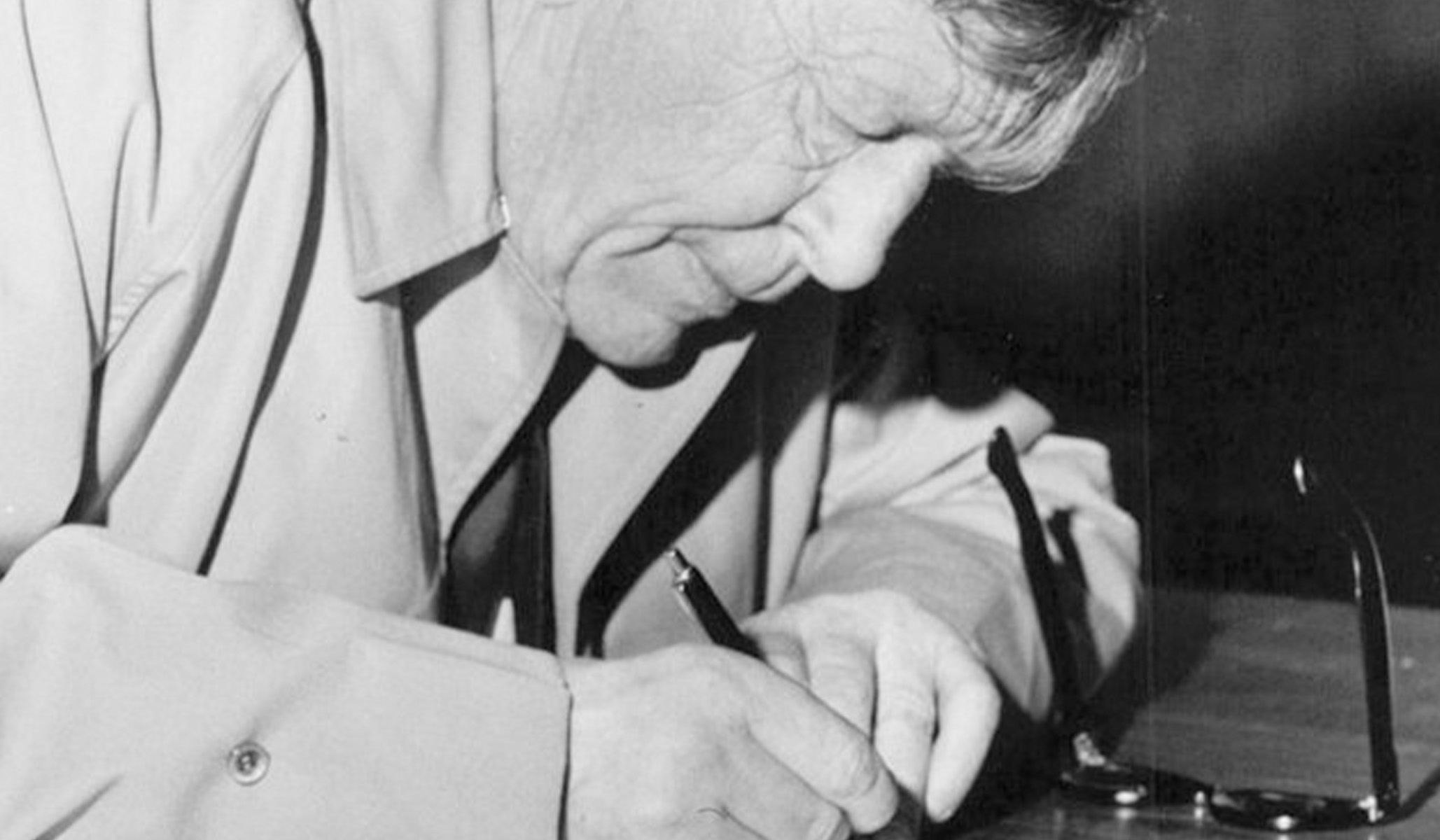

Edward Mendelson’s two-volume collection of Auden’s poems, spanning 1927 to 1973, is a welcome arrival, compiled by sage hands. “After Reading Psalm Twenty-Seven,” never reprinted until now, is a small example of the worth of Mendelson’s achievement. The literary executor of Auden’s estate, the author of several critical studies of his work, and the Lionel Trilling Professor in Humanities at Columbia, he is perhaps the poet’s best reader.

Great poets, it has been said, require great readers — yet they benefit most from great curators. Mendelson’s sensibility is well suited to Auden’s unique nexus of the sacred and the profane, the pious and the playful. Writing about Auden’s religious sense, Mendelson shares a perfect anecdote. Raised Anglican, Auden attended Saint Mark’s in-the-Bowery, an Episcopal church in Manhattan’s East Village. In the late 1960s, Father Michael Allen requested his input on liturgical revisions.

“Have you gone stark raving mad?” Auden begins his letter in response. Their church, he wrote, “has had the singular good-fortune of having its Prayer Book composed and its Bible translated at exactly the right time” — meaning, “late enough for the language to be intelligible to any English-speaking person in this century,” and early enough that “people still had an instinctive feeling for the formal and the ceremonious which is essential in liturgical language.” Preaching could be contemporary. “But one of the great functions of the liturgy,” Auden argued, “is to keep us in touch with the past and the dead.”

Despite his initial, cantankerous response, Auden “spent hours discussing and revising” the proposed liturgy, Mendelson notes. Yet when Saint Mark’s “actually began using a new liturgy, Auden quietly moved to a Russian Orthodox church nearby, where the liturgy was still in Old Church Slavonic. He chose to join a ritual that linked him to the dead and the unborn, but only after he had helped his neighbor.”

That final line arrives with characteristic Auden flourish, though it flows from the pen of his executor. Like great translation, great curation requires the often conflicting impulses of critical distance and emotional inhabitation. Both are required for authenticity.

These dual volumes show Auden’s evolutions and incarnations — and, finally, bring his substantial religious sense into clear focus. He was publicly coy about his faith, but those who knew him best were aware of his inclinations. “If Auden had his way, he would turn every play into a cross between grand opera and high mass,” Christopher Isherwood once said.

During his teens, Auden traded religion for poetry. He started his long return back to the church nearly a decade later. He wrote about a summer night when “sitting on a lawn after dinner with three colleagues” he felt “invaded by a power which, though I consented to it, was irresistible and certainly not mine.” He realized, for the first time, “what it means to love one’s neighbor as oneself.” The colleagues were neither lovers nor even “intimate friends” — but still, “I felt their existence as themselves to be of infinite value and rejoiced in it.”

When he made his way back to services, he remained hesitant about sharing his faith. (In a letter to T. S. Eliot, Auden described his return to the church and added a parenthetical request: “Please don’t tell anyone this.”) Auden likely realized that he should strike an intellectual pose in his religious verse — the secular world offers a gentle nod of acceptance when biblical or ecclesiastical references populate primarily nonsectarian verse. For them, God talk is fine; piety is perilous.

Yet even a casual journey through Auden’s collected poems reveals that the poet couldn’t help but speak the language of his faith. “The real world lies before us,” he writes in a poem from On this Island (1936):

Animal motions of the young.

The common wish for death,

The pleasured and the haunted;

The dying master sinks tormented

In the admirers’ ring,

The unjust walk the earth.

He strikes similar notes in “New Year Letter,” from The Double Man (1941): “The situation of our time / Surrounds us like a baffling crime.” “How hard it is to set aside,” the narrator admits, “Terror, concupiscence and pride” while we “Learn who and where and how we are, / The children of a modest star.” Later in the poem, he affirms, “Our best protection is that we / In fact live in eternity.”

Auden wrote “New Year Letter” during the first months of 1940. He was also reading Søren Kierkegaard and Paul Tillich, Mendelson notes. By the end of the year, Auden had returned to the Anglican Church.

In 1946, he wrote a commissioned poem for the Church of St. Matthew, Northampton. When accepting the commission, Auden stipulated “two demands”: that the fee “shall be a bit more than you can afford” and that “you shall donate it to any fund for the relief of distress in Europe which does not intentionally exclude the Germans.”

The second stanza of the work is titled “Bless Ye the Lord” and arrives with honesty: “We elude Him, lie to Him, yet His love observes / Its appalling promise.” Yet “our bodies” are “too blind or too bored to examine.” Although “our minds insist on / Their own disorder as their own punishment, / His Question disqualifies our quick senses, / His Truth makes our theories historical sins.” The poem’s conclusion is stirring: “And when we are wounded that is when he speaks our / Disconsolate tongue, concluding his children / In their mad unbelief to have mercy on them all.”

The distance between wit and sentiment is never far. In a single interview (with the Hudson Review in 1950), Auden could be humorous (“If I had children, I would want them to be either physicists or ballet dancers. Then they’d always have a job”) and deep (“It seems to me that in man’s search for God, he erects before him a number of images”). “Christianity is a way, not a state,” Auden said, “and a Christian is never something one is, only something one can pray to become.” His playfulness and emotional range was a function of how he saw the world: languid, and perhaps vicious at our worst, but never beyond hope. Worthy of salvation.