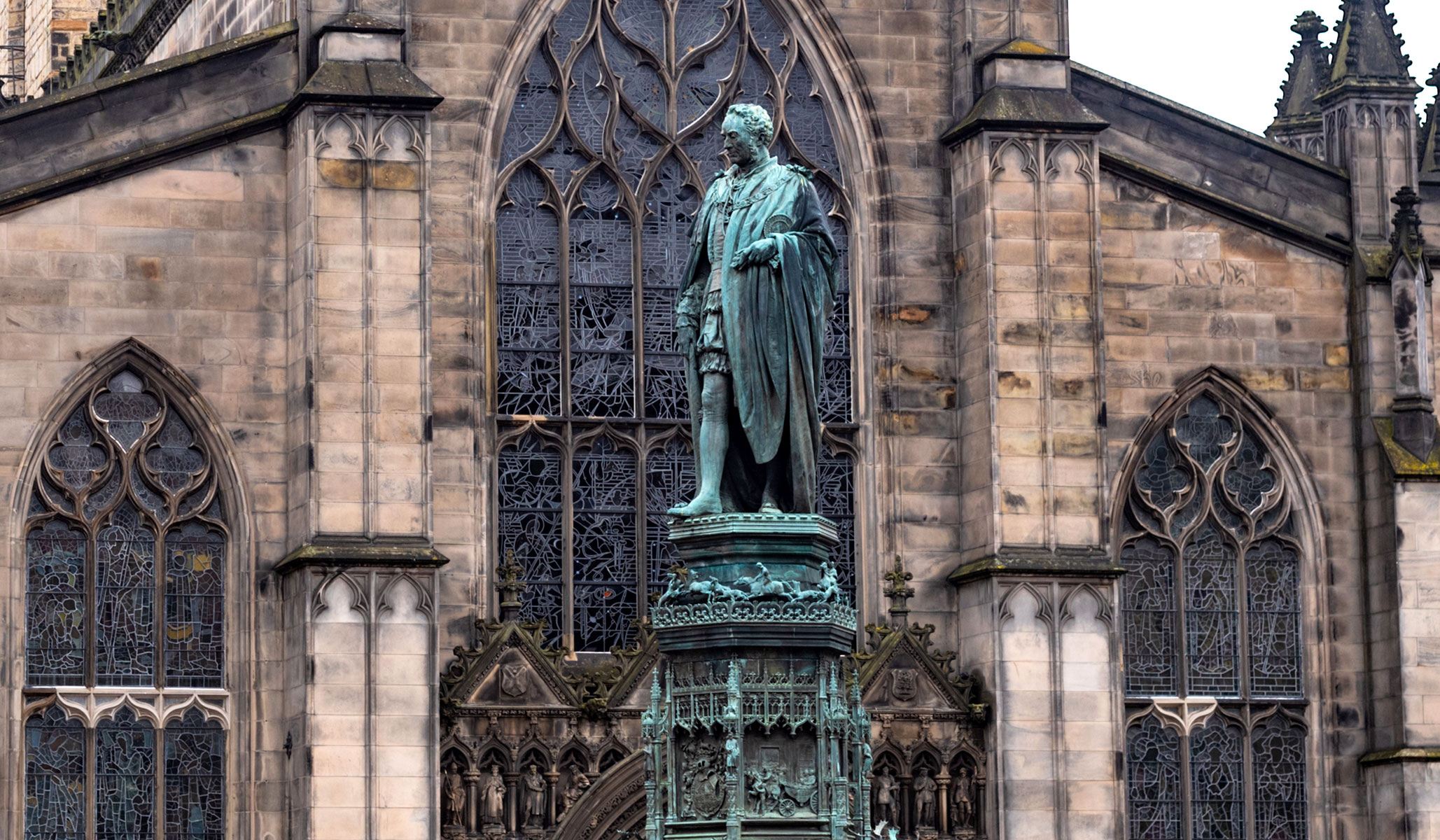

Adam Smith was born in 1723. This year he turns 300.

To celebrate, National Review Capital Matters offers the Adam Smith 300 series. An essay on Smith will appear monthly throughout 2023, written by various students of Smith’s thought. Smith’s birthday is June 16, so the essays will appear on the 16th day of each month. Daniel Klein and Erik Matson of George Mason University are helping curate the series for Capital Matters along with Dominic Pino. To read previous months’ essays, click here.

NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE A dam Smith has been portrayed as the father of economics, and as a founder of classical liberalism. Such portrayals tend to invoke a solitary genius whose ideas emerge from nowhere to change the world. But that is almost never the case. Thinkers such as Smith come from somewhere, and their ideas are shaped by their reading and participation in debates with their peers.

The Scottish Enlightenment took place in the middle years of the 18th century and was part of a wider European Enlightenment, the “Age of Reason,” when science, progress, and freedom of expression and activity came increasingly into the intellectual vanguard.

There is little mystery as to why the emerging Scottish literati took up the ideas of progress and enlightenment. Scotland emerged from a traumatic 17th century, typified by religious fanaticism, civil war, famine, and national bankruptcy. After the Union of Parliaments with England in 1707 and the defeat of the final attempt to return the Stuart kings in the Jacobite rebellion of 1745–46, Scotland experienced a long period of relative civil and political security as part of the new state of Great Britain. With political stability came economic transformation as Scots gained access to new markets in Great Britain and its colonies in the Americas. Growing industries such as linen, tobacco, and banking drove spectacular economic growth, which came with urbanization and rapid social change.

The literati were a tight-knit group living in the Scottish Lowlands, and more particularly in Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Aberdeen. The literati came from very similar middle-class backgrounds. They benefited from the Presbyterian emphasis on literacy and Scotland’s excellent local schools and universities.

Teaching in the Scottish universities had been transformed by the introduction of the latest work in science and moral philosophy by such figures as Colin Maclaurin and Francis Hutcheson. Maclaurin was a disciple of Isaac Newton and ensured that the modern scientific method was embedded in the university curriculum. Hutcheson, sometimes referred to as the “father” of the Scottish Enlightenment, developed the style of philosophical education that became the backbone of the Scottish universities. His moral-philosophy curriculum ensured that students read widely across ethics, jurisprudence, aesthetics, politics, sociology, and philosophy of religion. Hutcheson provided a system of moral philosophy designed to be useful to students, molding them into virtuous citizens and good Christians. Scottish education had a social as well as an intellectual function, and this notion deeply influenced Adam Smith’s understanding of what was expected of him when, in 1752, he took over the chair at Glasgow that Hutcheson had occupied.

These ambitious young men found their way into jobs in the universities, the Scottish state church, and the law. It is noteworthy that the Union of 1707 meant the dissolution of Scotland’s parliament in Edinburgh, as Scottish parliamentarians now went to Westminster. Scotland was now peripheral to the parliament governing the land. The end of the Scottish parliament may have opened up space in Scottish society for an elite more focused on culture than government.

Among their number were figures such as the “father of sociology,” Adam Ferguson; the judge and critic Henry Home, Lord Kames; Smith’s student and fellow professor at Glasgow John Millar; the great natural scientists Joseph Black, who discovered carbon dioxide, and James Hutton, father of geology; Hugh Blair, the first professor of English literature in the world; the philosopher Thomas Reid, who succeeded Smith at Glasgow; the best-selling historian and church leader William Robertson; the engineer James Watt; the architect Robert Adam; and medical men such as John Gregory, William Cullen, and the brothers John and William Hunter. At the center of it all stood Smith’s great friend David Hume, the brilliant philosopher and historian whose ideas proved so influential on Smith’s intellectual development. The Edinburgh professor Dugald Stewart and others carried the tradition into the 19th century.

Many of the literati were ministers of the Church of Scotland, called the Scottish Kirk. Robertson, Blair, and Ferguson led a moderate faction of ministers who worked to introduce enlightened ideas to the Kirk. They saw it as a potential vehicle for improvement. This marked the Scottish Enlightenment as decisively different from the French Enlightenment, where those known as the philosophes were implacably opposed to the Catholic Church and drew a sharp line between enlightenment and established religion.

Members of the Scottish Enlightenment could see the benefits of economic development, and they wanted to encourage the process. The idea of “improvement” became central to their sense of themselves as a group. Clubs such as the Edinburgh Society for Encouraging Arts, Sciences, Manufactures, and Agriculture, the Select Society, the Poker Club, and Adam Smith’s own Oyster Club, would meet to share the latest advances in knowledge. The clubs debated ideas from around the world along with the latest Scottish ideas. The leading Scots corresponded with and met the leading intellectuals of the time, with visitors such as Edmund Burke and Benjamin Franklin welcomed into what the Scottish novelist Tobias Smollett described as “a hotbed of genius.”

Thinking about this as the world where Smith formed his ideas helps us to understand why he was interested in the particular issues that find their way into his writings. The discussions were philosophical but had a practical focus: How could Scotland develop? How could society be improved?

From the Scottish cities of Edinburgh and Glasgow, they could see the beginnings of urban commercial society and modern agriculture in the Scottish Lowlands, but they could also look north to the Highlands and see a clan-based subsistence economy. The difference fascinated them and posed the question of how the Highlands might be “improved.”

The Wealth of Nations is filled with Scottish examples. Smith had around him a living laboratory of rapid social development. But like his fellow literati, Smith’s interests were not parochial. He believed that the attempt to generalize from the experience of a particular country would allow for the understanding of universal features of social life. Drawing on the work of earlier political economists, Smith attempted to create a scientific study of what he could see going on around him in Scotland, Britain, and the British Empire.

In exactly the same way, his Theory of Moral Sentiments was an attempt to apply science to our understanding of how people make moral judgments. The goal here was to examine how people come to form ideas about how they should live their lives. For Smith, this meant examining how people in different circumstances have different ideas about what constitutes right and wrong. Smith was able to use this empirical study to inform a new theory about the virtues appropriate for a commercial society. The point was not to preach virtue, but rather to allow his students and readers to see into their own thought processes and understand the operation of the impartial spectator who informed the voice of their consciences. Thus edified, they would be better able to make the right decisions, whatever the circumstances they might find themselves in.

Adam Smith was a man of the Enlightenment, and particularly of the Scottish Enlightenment. Once we grasp this, we can see why he was so interested in society, morality, and political economy. We can see why science was so vital to his understanding of the world and why he was so committed to the idea of improvement. We can appreciate the context that shaped his view of the world and sense a mind and spirit that, even after 300 years, continues to speak to us today.