NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE N ew York Times columnist Thomas Edsall tried to do a victory lap yesterday over the supposed failure of Republican-backed election-integrity laws. Instead, he merely showed that he didn’t understand the purpose of those laws in the first place:

Barack Obama’s successful campaign for the presidency in 2008 had provoked fear in Republican ranks that the conservative coalition could no longer maintain its dominance. Getting 52.9 percent of the popular vote, Obama was the first Democratic presidential nominee to break 50 percent in the 32 years since Jimmy Carter won with 50.1 percent, in 1976.

Republicans counterattacked, mounting a concerted drive to disenfranchise Democrats, a drive that gained momentum with the June 2013 Supreme Court decision Shelby County v. Holder. The court ruled that Section 5 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which required states and jurisdictions with a history of discrimination to obtain preclearance for any change in election law, procedure or regulation, was unconstitutional.

Luckily, Edsall argues, new research shows that voter-identification requirements, rollbacks of early voting, and related laws tend to have very little effect on the outcomes of elections. Even the number of “minority opportunity” districts, which are designed to allow racial minorities greater control over the outcome of congressional races, went up in states that were affected by Shelby County. Of course, Edsall can’t accept that election-integrity laws were never intended to manipulate election outcomes in the first place. Instead, he asserts that “the American electorate is determined to exercise the franchise and is resistant to legislated hindrances.”

Voter-turnout data might suggest otherwise. Yet, despite Edsall’s mischaracterizations of the purpose of these laws, the piece ultimately defangs the apocalyptic rhetoric Democratic politicians often employ around the issue. It’s simply not that difficult for most people to get state IDs and to go vote in person on Election Day. Republican politicians by and large write those requirements into law not because they impede voting but because they protect it. It’s hard to accept the argument that these laws are an attack on our democracy when one realizes that “turnout in the 2020 presidential election was the highest in 30 years.”

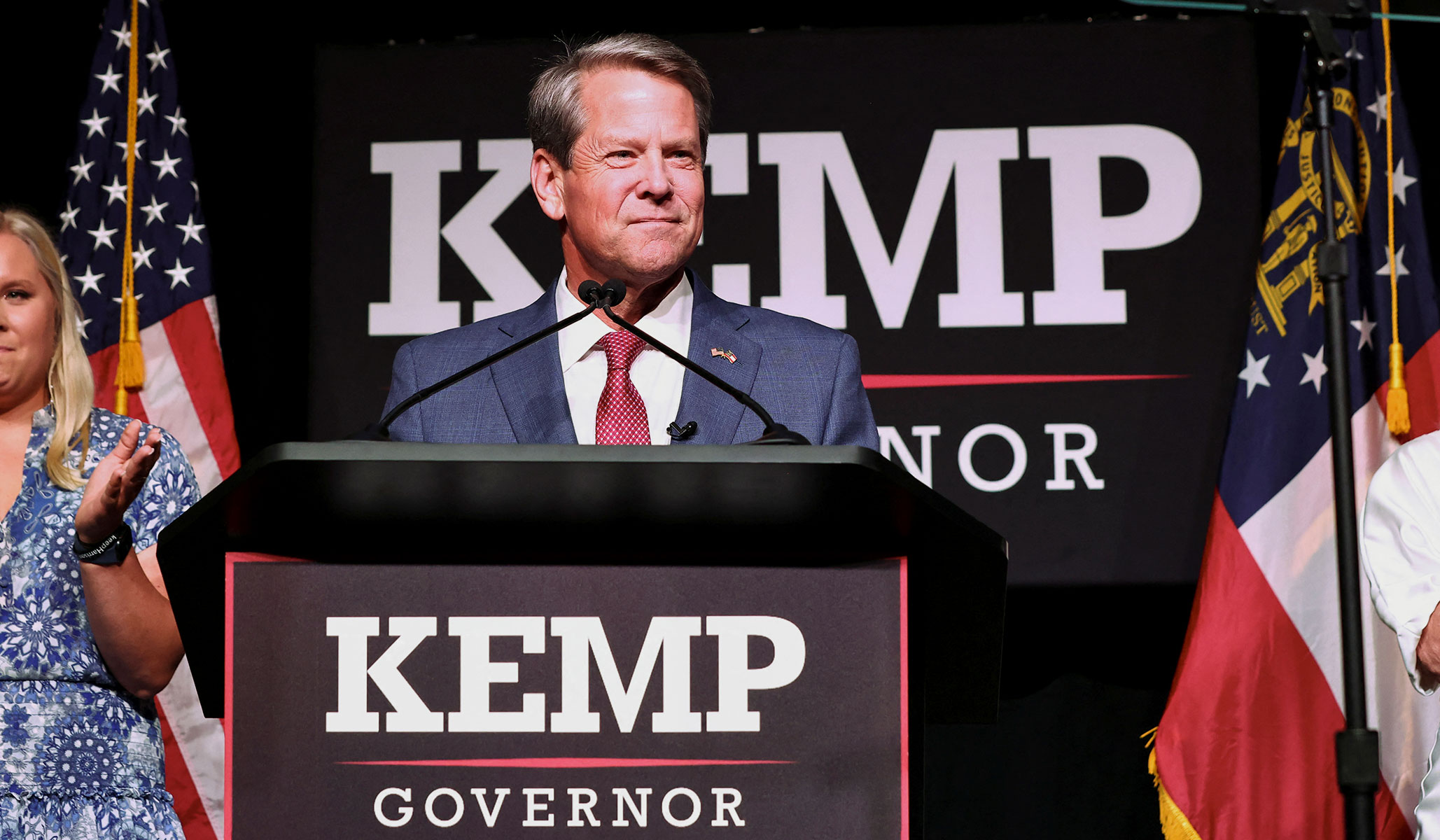

Consider Georgia. Republican governor Brian Kemp signed a bill in 2021 that made changes to the state’s elections law such as implementing stronger voter-ID requirements for absentee ballots. President Biden subsequently called the law “Jim Crow in the 21st century” and argued that it would disenfranchise black voters. A University of Georgia poll after the 2022 election, however, found that 0 percent of black voters statewide rated their “overall experience voting” as poor. It also found that more black Georgia voters thought voting had become easier from 2020 to 2022 than thought it had become more difficult.

Edsall’s portrayal of the motivation for these laws is somewhat surprising because he quotes the following from Justin Grimmer and Eitan Hirsh, the authors of one of the studies he heavily draws from:

First, there are a lot of reasons legislators, activists, or political parties might want to reform laws that have nothing to do with the change in laws affecting outcomes. For instance, changing laws might improve the functioning of elections and increase trust in the electoral process. We might think some changes to election laws are simply the right thing to do based on our ethical values.

This is a far better explanation of the point of these laws than any of Edsall’s surrounding commentary. Voting rights are a sign of membership in our political community. Failing to take proper precautions to ensure they are only exercised by those legally eligible to exercise them, in a legal manner, degrades the value of citizenship. Voting goes from an act of stewardship over the community to an exercise in power politics. Avoiding this reframing is “simply the right thing to do.”

Of course, opponents of election-integrity laws often argue that they are unnecessary, as documented cases of voter fraud are relatively rare. Like it or not, however, trust in our electoral system has declined in recent years. Elections are intended to produce political outcomes we can all live with; feeling that one’s voice was at least heard staves off a complete rejection of the results when one loses. But if voters don’t believe that an election was conducted fairly, these effects are lost. If voter-ID laws and the like will convince some voters that they can once again have confidence in the results of American elections, that is a good reason to pass them. Edsall may have thought he was demonstrating the pointlessness of election-integrity initiatives. All he really showed was that Republicans’ preferred means of restoring public confidence in the democratic process aren’t biased after all.