Saxony’s dukes certainly had good taste.

NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE T he Zwinger Palace in Dresden is a triumph of German court architecture. It also displays one of the world’s most extraordinary collection of Old Master paintings. It might be the most jaw-dropping and extraordinary Old Master collection anywhere. The iconic Raphael, the big mama of all his Madonnas, acres of Rubens, and Rembrandts, Rococo pastels, weird Cranachs, as well as Canalettos and Bellottos galore make the Zwinger a place to be for an art high. It’s the Old World at its most enchanting and opulent.

“Zwinger” is the German term for a border fortification, which once existed on the site. As Dresden expanded, the land, prime real estate, became an orangery and, by the 1720s, a pleasure palace with pavilions, galleries, and courtyards for processions and festivals.

Augustus the Strong (1670–1733) is the Saxon ruler who made Dresden a culture capital and built the Zwinger. Strong in will, strong and steely in ambition, Augustus gave us Dresden’s look — serene, whimsical, and glorious, a surprise since Augustus was strong physically, too. He could break a horseshoe with his bare hands. He acquired a chunk of its Old Masters collection, and his successors bought well for a hundred years after his death. He established the porcelain factory at Meissen, too. Very international, he saw Dresden as the new Venice or the new Florence and its royal precincts as sculpted and elegant as Versailles.

His day job was duke of Saxony, king of Poland, and grand duke ruling Lithuania, Kyiv, Smolensk, and a dozen other places with names from Marx Brothers movies. So, strong in time management, but being a despot helps cut red tape. Though the Holy Roman Emperor was invariably a Habsburg, Augustus was among the handful of electors who made it official.

And he is said to have sired over 350 children, so he was strong in sex drive and stamina as well as practiced in saying “hasta la vista” to expectant ladies, surely in multiple languages.

Alas, an aggressively graceless admissions pavilion greets the visitor. It’s inevitable, given modern museumgoers, but the Zwinger has been a public gallery for 150 years. It never needed a cavern for admissions, coats, a shop, and lockers. Visitors go down to the cellar, pay, disrobe, store their bags, get their tickets scanned, and then go back up for art, in an elevator or the backstairs. Was I in a Midtown office building?

Great museums deserve grand entrances, and museums made from palaces invest in the visitors the divine right to enter like kings, or at least dukes and electors. A peeve of mine.

The Zwinger’s website needs an overhaul. It’s positively Italian.

These are my only quibbles. In walking through the dazzling galleries, I didn’t think a lot about where this or that painting fit in the career of this or that artist. Instead, I thought about the tastes of the dukes who bought the art and, of course, lighting, labels, and arrangement. The galleries are arranged by school and chronology, more or less, and the first galleries I saw, aside from the conservation ones, were Dutch and Flemish, anchored by Rembrandt and Rubens.

Augustus and his only legitimate son, Frederick Augustus (1696–1763), had superb, idiosyncratic taste. Both collected with intensity. They must have spent a fortune on art. Their agents in Holland, Italy, and France were bloodhounds, diplomats, and bullies.

The Rembrandts are brilliant but tough. The Abduction of Ganymede, from 1635, is one centerpiece. It’s a big thing depicting Zeus, as an eagle, grabbing the toddler Ganymede, who’s screaming bloody child rape. Self-Portrait with Saskia in the Parable of the Prodigal Son is from 1637. The artist and his wife are models, playing “gross Leben” types, which is my German for “livin’ la vida loca.” It’s prophetic, too. In a few years, Rembrandt would be a bankrupt.

A third — and big — Rembrandt is Samson Tells a Riddle at the Wedding Feast, from 1638. “Out of the eater comes meat, out of the strong comes sweet,” Samson, the invincible giant, posits at his wedding feast. Yes, it’s cryptic. Samson had just killed a lion, whose belly was full of honeybees, but it’s a show-stopper. The Last Supper by Leonardo inspired the composition. Not something any old dumb-ass royal would buy. “Out of the strong comes sweet” is a tribute paid to Augustus — who bought the painting — and to autocrats everywhere.

For comic relief, there’s a six-footer across the gallery. In The Dentist, by Honthorst, the doc looks like a quack, and his patient is clearly in extremis, but he’s doing his best and means well.

These are wonderful pictures but not safe ones. The Wettins — Saxony’s ruling family — had edgy taste. Complex, multi-figure compositions abound. And they had a taste for going big. The Zwinger was built to accommodate big art, and the collection is rich in Italian altarpieces. Correggio, Tintoretto, and Veronese altarpieces are movie-theater scale and match on canvas a ducal love of theater and spectacle. Double hangings make for a splendid effect. Dark red, blue, and green wall colors are perfect for Old Masters.

St. Roch Distributing Alms was painted by Annibale Carracci around 1594. The Zwinger calls it the first Baroque history painting for its intensity and dynamism. Frederick bought it from a confraternity in Reggio Emilia in the 1740s. I don’t think he knew what art historians would consider it, and it’s a religious rather than a history painting, but I do think he understood that Carracci was, in his day, doing something different.

The Wettins weren’t particularly pious or dogmatic. Augustus switched from Protestant to Roman Catholic to become king of Poland. Secular and religious art each have heavy hitters. Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus, from 1510 — said to be the first reclining nude in Western painting — is secular. The Sistine Madonna, by Raphael, in the next gallery, isn’t. Diogenes Searching for an Honest Man, by Jacob Jordaens, from 1642, is near the Rubens altarpieces.

The Sistine Madonna by Raphael, commissioned by Pope Julius II in 1512 for a church in Piacenza, is a picture everyone knows, if only for its putti. When Frederick Augustus pried it from the church in 1754, he paid what was then the highest price ever for a painting. Displayed at the Zwinger, it immediately became a symbol of the city. It’s got the grand vista in the museum, visible from one end of the museum to the other, where it’s displayed with altarpieces by Correggio.

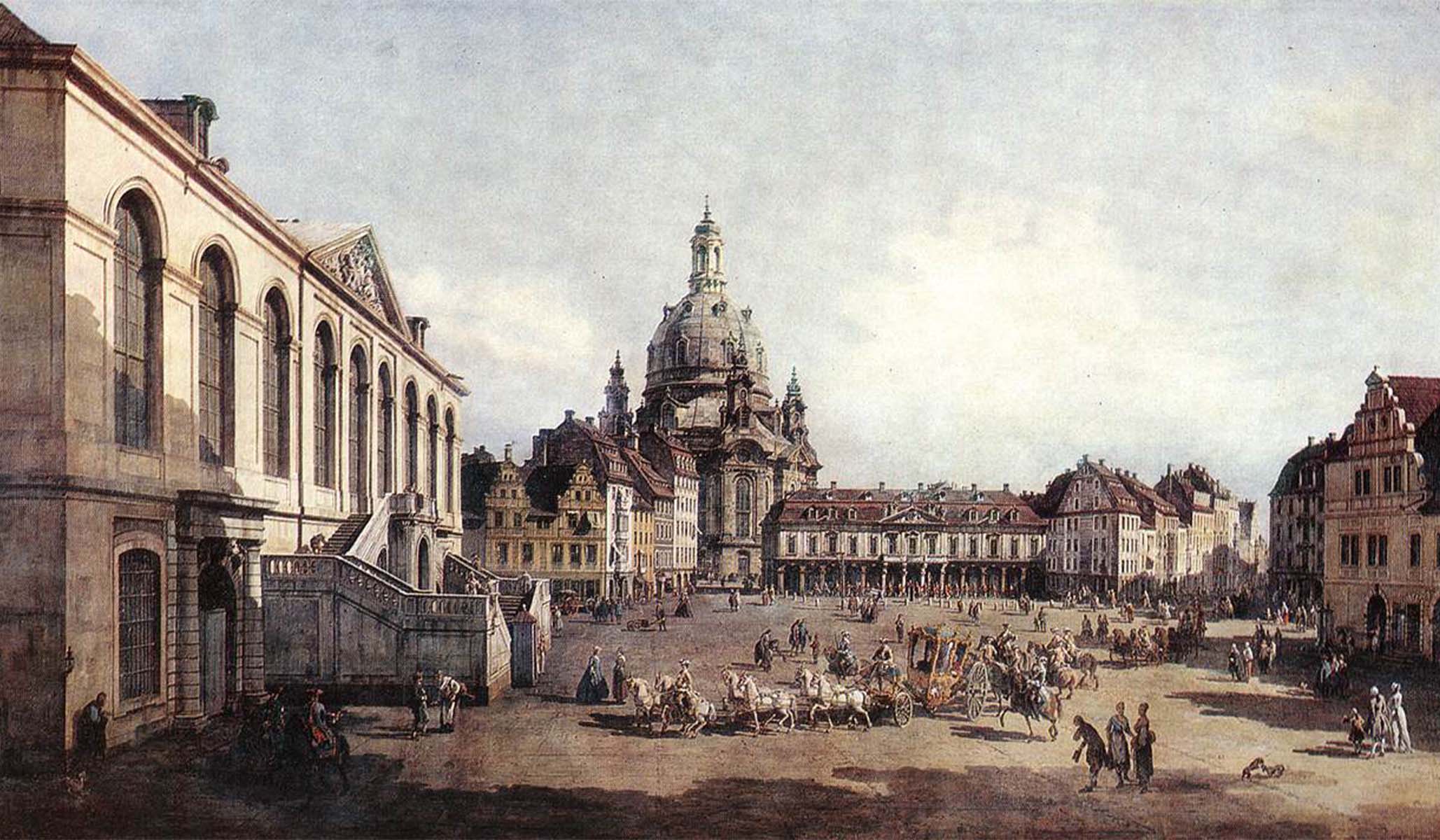

And all of this is in only one floor of the Zwinger. The floor above doesn’t have the same high ceilings and spacious galleries, but passages of brilliance give us another perspective on the ducal paintings collection. First, there’s Bellotto’s cycle of views of Dresden. Bellotto, Canaletto’s nephew, was from Venice and painted in a documentarian, crisply detailed style of his uncle.

Frederick Augustus, sharing his father’s view of Dresden as the new Venice, hired him in the 1740s to paint the city. Venice at that point was on the way down, lovely and partying but broke. Mostly it was a Renaissance city. Dresden was a commercial, political, and cultural powerhouse, on the way up, and the city’s signature buildings, among them the Zwinger, were new.

We call the Zwinger a gallery of Old Masters, and it is, but a big part of the collection, including the Bellottos, was bought as the work of a living artist. Bellotto was contemporary. So are the two dozen pastel portraits by Anton Raphael Mengs, Jean-Étienne Liotard, and Rosalba Carriera. The Liotard Chocolate Girl, from 1745, was purchased directly from the artist by one of the duke’s agents. Its surface is flawless and porcelain-smooth, with the most delicate palette. It became famous soon after it was done. The pastels get their own gallery. Entering it is like opening a jewel box. Frederick Augustus saw himself as a contemporary art collector, sometimes commissioning work from artists such as Giovanni Piazzetta, Angelica Kauffman, and Nicolas de Largillière.

The last gallery I visited was far from contemporary. It stars Lucas Cranach, Elder and Younger. The Sleeping Hercules Beset by Pygmies, from 1551, by Cranach the Younger, is the kind of picture Richard Wagner must have absorbed. It’s very German, and Wagner lived in Dresden for decades. I’m here to see The Ring Cycle at the Dresden opera house. An aesthetic like Cranach’s has to have had an impact on the composer and storyteller who gave us the Gibichungs, the Valkyries, the Nibelungs, and the Giants. And let’s not forget that Wagnerian romance is more often than not incestuous. The Cranachs are that weird, and that mesmerizing.

I think the Zwinger is very little known among Americans. Dresden is a big business hub, but I don’t think it’s particularly touristical. Of course, until 1990 it was part of East Germany. Communist rule wasn’t bad for East Berlin. As a capital city, it sucked a lot of government money, giving it a bit of polish. Dresden, Leipzig, and Potsdam, among others, were very much the neglected stepchildren.

There are famous paintings at the Zwinger, to be sure. The Sistine Madonna is famous. The collection includes two Vermeers. Antonello da Messina’s St. Sebastian, from around 1478, and the Giorgione Venus are well-known male and female Renaissance nudes. These are art-history staples. Sublime as everything else is, much at the Zwinger isn’t well known. That’s a treat.

I’ll write next week about the Zwinger’s Meissen collection, which is in another wing and is spectacular.

The Zwinger’s exhibition of the sculpture of Dresdener Paul Heermann (1673–1732) was a revelation. I’d never heard of him. He worked for Augustus’s court in Dresden in a style that’s called German Baroque, but it’s eclectic and anticipatory. Heermann was part of Dresden’s art establishment, and his sculpture suggest the muscular, rocket thrust of, say, Bernini, revered as a god by Heermann’s uncle Johann, the chief Saxon court sculptor. Johann worked in Rome, where Bernini was the ubiquitous genius. Returning to Dresden, he made Bernini the point of reference for Saxon sculpture.

Dresden artists were less derivative and more like amalgamators and seers. The Dresden and nearby Prague courts were international. Roman, Venetian, and Milanese styles as well as the latest from France and the Netherlands mixed. Heermann’s figures have big, deeply drilled eyes, so they seem soulful, even grave, and that’s Italian, but their bodies are ever so attenuated and lithe, and this feels French and ever so rococo.

Well-traveled art patrons and courtiers knew what lay on the aesthetic horizon, and Dresden’s best artists, such as Heermann, made it their business to know as well. Heermann’s light touch seems more intuitive than learned. His work is serious and solid but flirts with giddy oomph.

The Zwinger is visual opera. It’s a tonic for serious art lovers. “Hojotoyo, hojotoyo, heiaha, heiaha,” as Brünnhilde sang, in celebration of life, but she included among its pleasures this great gallery.