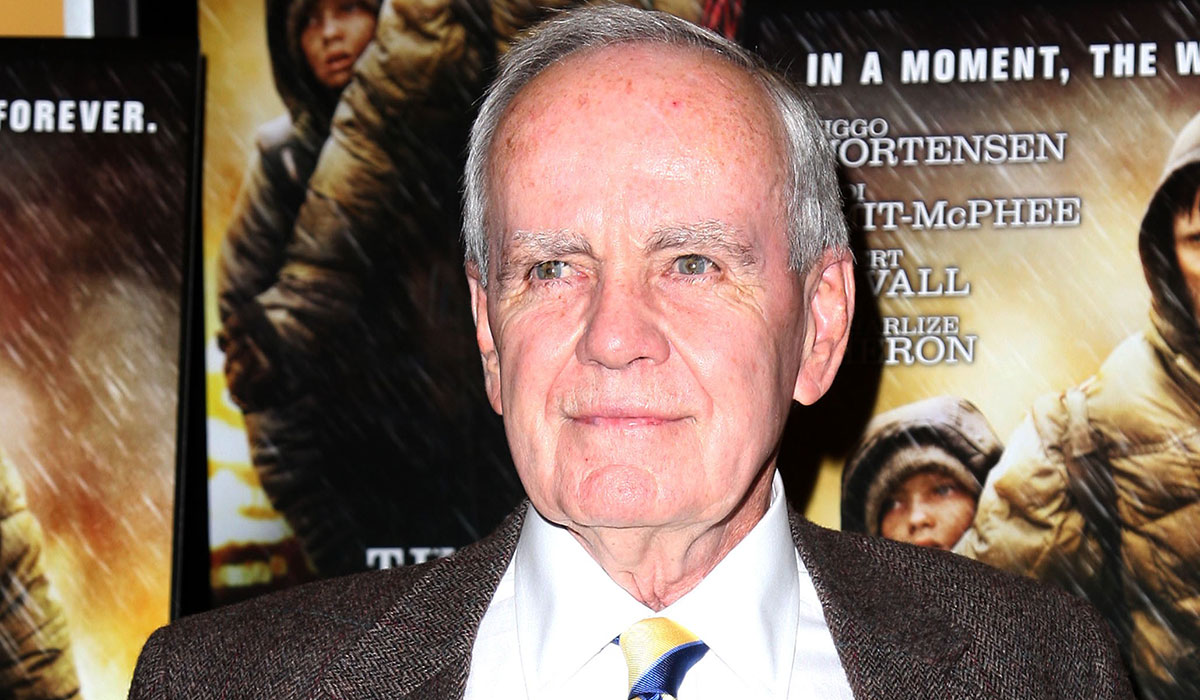

The storied author has crafted a cerebral, challenging, and surprising literary farewell (if it is indeed a farewell).

The Passenger, by Cormac McCarthy (Knopf, 400 pages, $30)

Stella Maris, by Cormac McCarthy (Knopf, 208 pages, $26)

NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE I f Cormac McCarthy’s novels are defined by any particular quality, it’s hostility to convention. He eschews the rules of grammar, constructing sentences that consume whole paragraphs and writing dialogue free of quotation marks. He depicts human depravity without regard for taboos, vividly exploring subjects ranging from incest to necrophilia. And though his stories are driven by realism, his endings are often intensely metaphorical, to an almost taunting degree.

All of these traits are present in The Passenger and Stella Maris, McCarthy’s latest novels and his first in 16 years. Published last year in October and December respectively, their announcement in March sparked a feverish anticipation among his readers. But their experimental style and occasionally bewildering subject matter will certainly alienate many. The novels are challenging, sometimes to the point of irritation, but they are buttressed by the same thematic richness that has elevated McCarthy’s greatest work. Together, they represent a literary farewell that can be deeply rewarding, though it’s best approached with an open mind and few preconceptions.

Set in 1980, The Passenger follows Bobby Western, a salvage diver in the Gulf of Mexico who discovers a downed airplane. Inside, one of the eight passengers on the plane’s manifest has disappeared alongside the pilot’s black box, but there are no signs of entry. When Western returns to land, he begins to be pursued by a pair of (ostensible) federal agents investigating his connection to the plane, who threaten his life if he refuses to cooperate. Eventually, he goes on the run, but it soon becomes apparent that he’s more concerned with escaping his inner demons than the government’s mysterious forces.

Western’s a tortured soul — a Caltech-educated scientist who abandoned physics to lead a lonely, working-class life in the American South. He’s haunted by the memory of both his father’s role in developing the atomic bomb and the death of his sister, Alicia, who suffered from schizophrenia. Her hallucinations — in which she’s menaced by the “Thalidomide Kid,” a grotesque, flippered creature who mocks her anxieties and leads a group of vaudevillians, among them a “matched pair of dwarves in little suits with purple cravats and homburg hats” and “two blackface minstrels in overalls and straw hats” — punctuate each chapter of The Passenger. Stella Maris is set roughly a decade earlier during Alicia’s time in a psychiatric institution and explores her illness through a series of conversations with her therapist.

On its own merits, The Passenger is a compelling novel, but Stella Maris has little to offer as a stand-alone work. It’s a companion piece that exists to illuminate some of the more cryptic plot elements of its sibling and to amplify the resonance of its themes. At its core, The Passenger is three things at once: an ironic reflection on McCarthy’s legacy that toys with aspects of his previous novels, an existential meditation on man’s search for the meaning of life, and an extended metaphor for the mind of post–World War II America. These threads consistently overlap, complementing one another throughout Western’s journey.

Blood Meridian (1985), often regarded as McCarthy’s magnum opus, follows a violent gang of scalp hunters as they wreak carnage across the American Southwest at the turn of the 1860s. In it, McCarthy focuses on the character of “the judge,” a hulking, bloodthirsty, yet exceptionally erudite man who seemingly cannot age. He is emblematic of the United States in the days of the Old West — inexorably bent on conquest, and animated by intelligence and rapid advancements in human knowledge. The Passenger places Bobby Western in a comparable but less wicked position. As Western drifts from state to state, much of the novel consists of conversations between him and his acquaintances, who each seem to possess some distinct struggle tied to America’s shifting culture. These range from a Vietnam veteran wrestling with trauma to a transgender woman searching for love in a moment of ascendant social conservatism.

Western himself, meanwhile, is as riddled with contradictions as the land he inhabits, embodying the disparate tastes and experiences of the American people. He’s a genius without goals or ambitions. An appreciator of fine dining who enjoys gorging on cheeseburgers at dilapidated bars. Capitalism brings him great wealth — he earns a fortune selling a collection of antique coins buried beneath his grandmother’s house — but he resides in meager surroundings and seems unconcerned with possessions.

McCarthy’s language brings both Western’s friendships and internal pain to life with brio, preventing the symbolism from feeling labored. His descriptions can be stunning in their power, such as when the Vietnam veteran recalls that, in war,

somebody next to you takes a round and it sounds like it’s hitting mud. Well. It is. You could have gone your whole life without knowing that. But there you are. You know every day that you’re someplace that you aint supposed to be.

His observations on humanity, moreover, are often as penetrating as they are sharply expressed. In one instance, one of Western’s companions predicts that extremism and moral decay will infect American society as it becomes increasingly prosperous and self-sufficient. “Real trouble doesnt [sic] begin in a society until boredom has become its most general feature. Boredom will drive even quietminded people down paths they’d never imagined.”

At times, the prose can sag under the weight of McCarthy’s scholarly ambitions. When Bobby and Alicia reflect on their father’s role in the Manhattan Project, the reader is bombarded with mathematical and scientific jargon. These sections are dense to the point of obnoxiousness, and those with no understanding of science will find them tedious at best and impenetrable at worst. The dialogue in both novels is usually captivating, but it can sometimes seem aimless as conversations extend for pages without offering new insights.

But there’s a subtle streak of wry humor to McCarthy’s voice that enlivens things when the pacing falters, and the playful references to his past work scattered throughout will delight loyal fans. Leaving aside the allusions to Blood Meridian, the carnivalesque creatures who torment Alicia evoke the overlooked Child of God (1973) and Suttree (1979), the latter of which also follows an alienated character through a series of strange encounters. McCarthy’s intent is seemingly to distill his oeuvre into a handful of pivotal themes and ideas while teasing the expectations of his devotees. In The Passenger, Bobby Western is referred to almost exclusively by his surname, its frequent use mocking anyone who may have hoped for a more straightforward tale in that genre.

Like No Country for Old Men (2005), The Passenger features a protagonist on the run from a sinister and unyielding force, raising questions of destiny and purpose. Bobby Western’s isolation is profound, and his fear that life is ultimately meaningless pervades the novel. Alicia is equally alone in Stella Maris, and she faces similar anxieties, which manifest in her delusions. “The passing of time is irrevocably the passing of you,” remarks one of Western’s peers. “And then nothing. I suppose it should be a comfort to understand that one cannot be dead forever when there’s no forever to be dead in.” For McCarthy’s characters, life is arbitrary and chaotic; it has no fairness or karmic balance. But despite that reality, the novels seem to affirm that embracing life is still ultimately a good in itself, whatever anguish and joy it may bring. “I don’t care how it will end,” Western proclaims as he recalls his sister’s love. “I only care about now.” Though The Passenger and Stella Maris may be grim, they offer an optimistic glimmer amid the darkness. If life ends in nothingness and is largely unjust, then there’s an enormous beauty to even the minor acts of kindness that Western regularly commits.

It’s appropriate that The Passenger and Stella Maris are preoccupied with how to live when McCarthy has made life so thoroughly his own. If these are indeed his final novels, then his career will end as independently as it began, untethered to the preferences or expectations of critics and readers alike. The Passenger and Stella Maris can be frustrating, baffling, and exhausting, but they are equally beautiful, engrossing, and thought-provoking. Much like life, they deserve to be experienced in all their complexity.