With each crisis, Europe shows its faults, and the war in Ukraine is no exception. Two years after Russia invaded the country, European states managed to stay united in sanctioning Moscow and supporting Kyiv on military, humanitarian, economic and political levels. However, this cohesive action could be severely tested if Donald Trump returns to the White House following the November presidential election, which would mean the US's level of solidarity is reduced. A discreet but very real divide has opened up over the months: The northeastern part of the continent is on a war footing, on the front lines against the Russian threat, while further west and south other countries have taken a less existential view of the conflict.

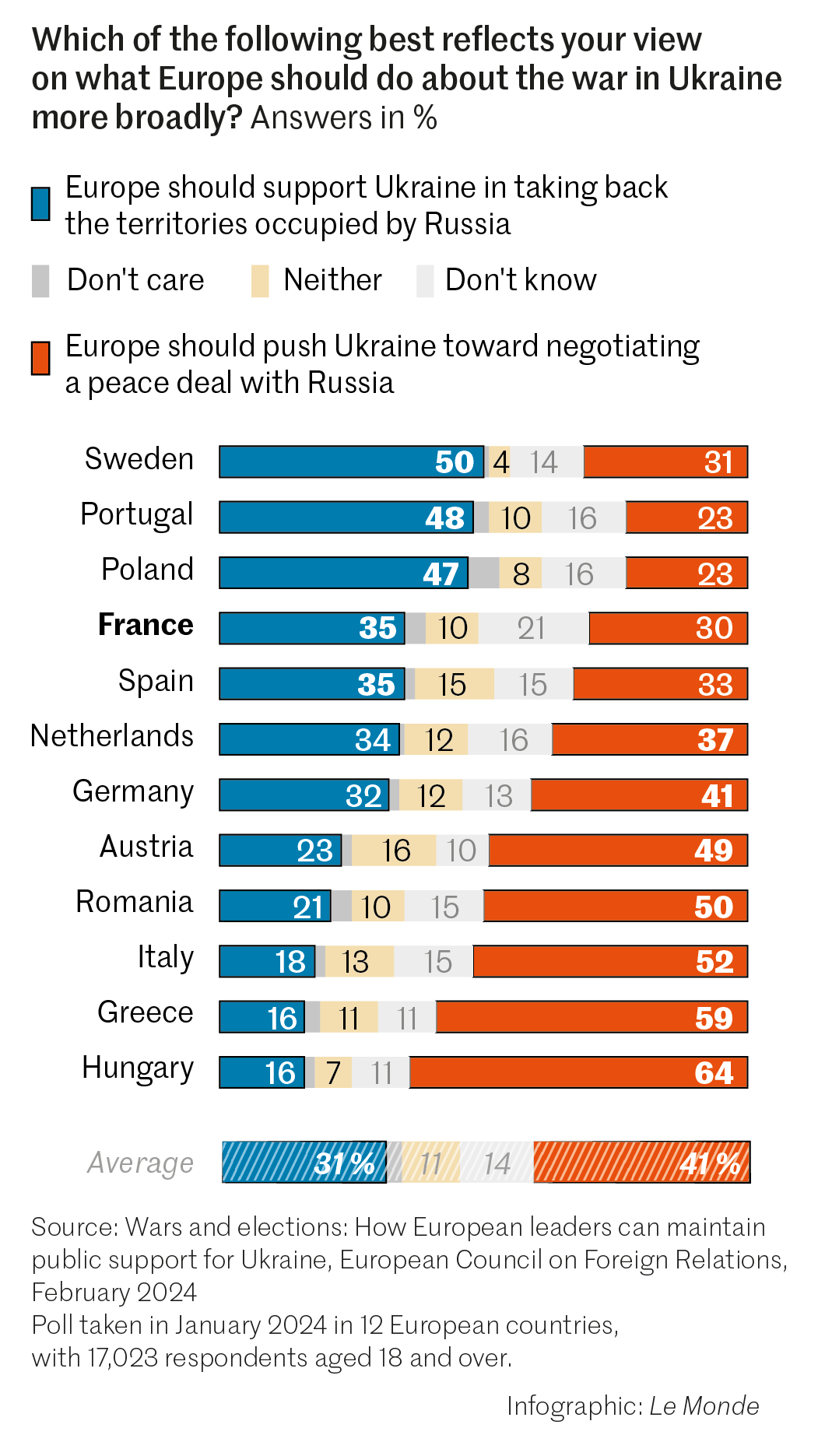

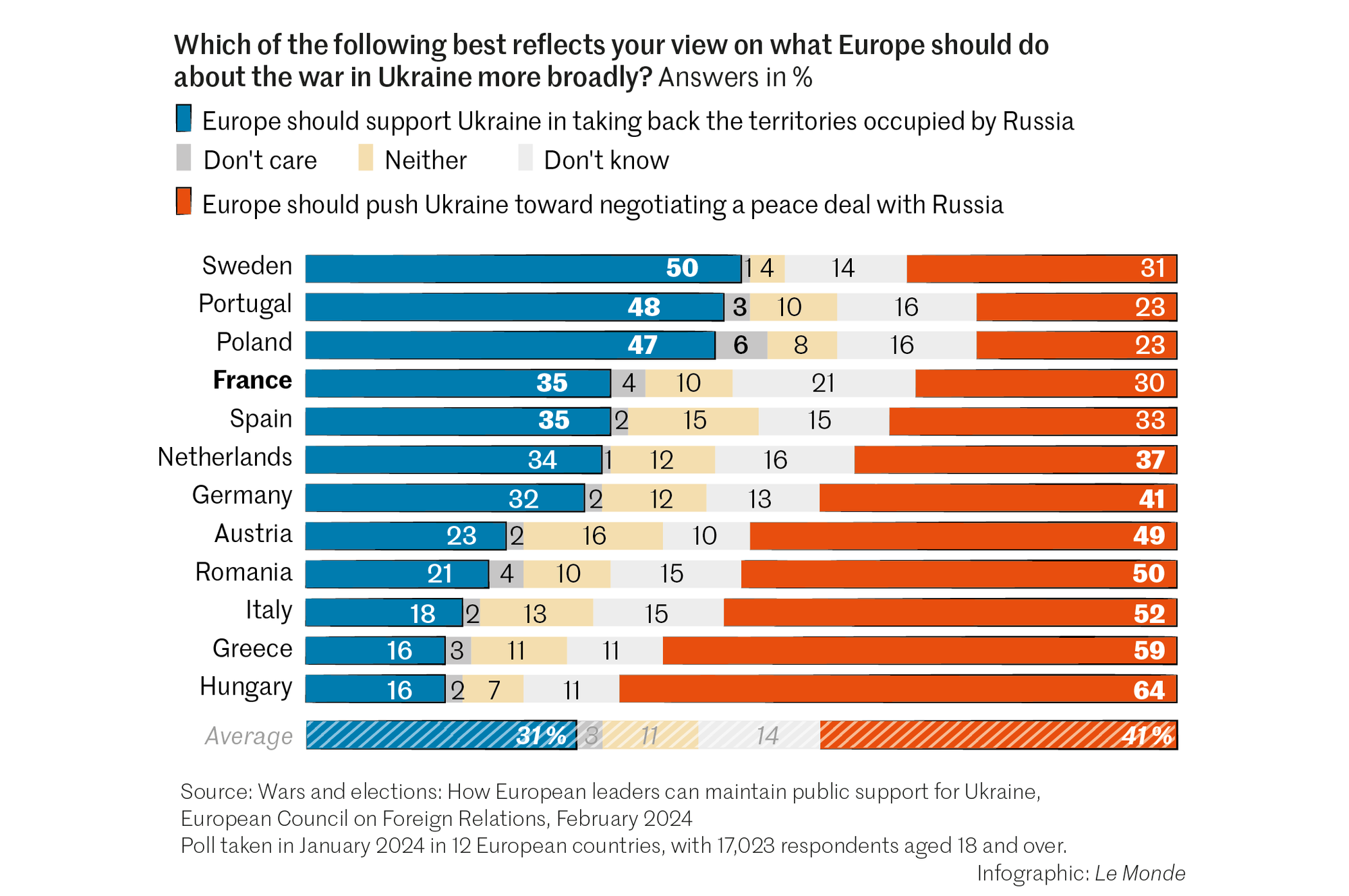

A poll carried out in 12 EU countries by the think tank European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), published on Wednesday, February 21, shows that the differences are not due to predictions about the conflict's outcome. On average, only 10% of Europeans believe in a victory for Kyiv, compared with 20% for Moscow (a relative majority anticipate some form of compromise), with little variation between countries. However, this does not prevent half of the people in Sweden, Poland and Portugal from advocating support for Ukraine in reclaiming its territories currently under Russian occupation. Conversely, half or more of Hungarians, Greeks, Italians, Romanians and Austrians want to push Kyiv to negotiate with Moscow. The French, Spanish, Dutch and Germans are more divided.

The various governments' policies have reflected these nuances. In the Baltic States particularly, mobilization remains strong. "We've been saying Russia is a threat for decades," explained Estonian Defense Minister Hanno Pevkur. On January 19, his country, along with Latvia and Lithuania, signed an agreement outlining the establishment of a defense line along their eastern border. It will be constructed starting from 2025 and will consist of 600 underground bunkers, barbed wire and other "anti-mobility" installations intended to slow the advance of Russian troops in the event of an offensive. "It's not a Maginot Line, but facilities that will be placed near the border in peacetime, and will allow us to gain time if we ever have to face the worst," explained Pevkur.

This initiative is just one of many adopted over the past two years by the Baltic states, which harbor no illusions about their security in the "medium and long term." In mid-January, Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas estimated that the European Union and NATO had "between three and five years" to prepare.

You have 78.34% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.