You could almost set your watch by it: Every 10 years, like clockwork, Versailles re-establishes its relationship with China. In 2004, the château explored the links between Louis XIV (1638-1715) and his contemporary, the emperor Kangxi (1654-1722), as part of the France-China Year of Relations. In 2014, the exhibition "China at Versailles, Art and Diplomacy in the 18th Century" marked the fiftieth anniversary of diplomatic relations between the two countries. And now, from April 1 to June 30, the public institution is exporting an exhibit with the title "The Palace of Versailles and the Forbidden City: French-Chinese relations in the 18th Century" to Beijing's Forbidden City.

The institution's president, Catherine Pégard, makes no secret of the fact that she would like to win back Chinese tourists, who accounted for 13% of her visitors before the Covid-19 pandemic, compared with 4% today. This exhibition, financed by patronage from the Cartier brand, ticks all the boxes for diplomacy, symbolism, and aesthetics. "Versailles is a common name in China, a symbol of elegance, chic, and style, and a place of power on a par with the Forbidden City," she said.

Louis XIV, who tolerated no rivalry, was fascinated by the Manchu emperor, who was 16 years his junior. To establish a relationship with him, he sent Jesuit missionaries in 1685. Fascinated by their scientific knowledge, the Son of Heaven welcomed them. The two monarchs forged long-distance ties, and 18th-century exegetes emphasized the parallelism of their destinies: the same youthful accession to the throne, equal longevity, and a shared curiosity for the arts. The Franco-Chinese friendship lasted until the French Revolution.

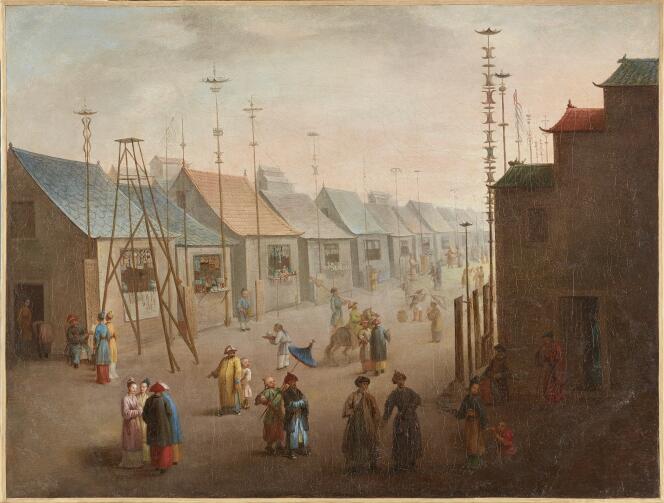

Political exchanges influenced the taste of the time. The court of Versailles was enamored with the celadon ceramics and goblets that flooded into France. Taking advantage of the taste for "Chinoiseries," cabinetmakers incorporated lacquer panels into their furniture. Bronze workers fashioned gilded mounts to magnify porcelain, while ceramics makers desperately sought to unlock the secret of its manufacture. The fascination was not one-sided. The Chinese emperor, in turn, was fascinated by the scientific instruments, sextants, goniometers (used to measure angles), and armillary spheres (used in astronomy) that the Jesuits brought with them in their luggage.

For a long time, the gifts of the kings of France slumbered in the basements of the Forbidden City (1.6 million works are kept in the Chinese palace's reserves, off-limits to foreign curators). When Catherine Pégard first made contact with the Beijing authorities in 2014, she received a reserved welcome. "At the time, Chinese curators were just beginning to take a renewed interest in a period that was considered to be decadent for political reasons, just 25 years ago," explained curator Marie-Laure de Rochebrune, co-curator of the exhibition at the Forbidden City.

You have 35% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.