It's a geophysical phenomenon that has science-fiction writers dreaming, astrophysicists fretting and space agencies reeling. Some of the natural satellites of Jupiter and Saturn hold oceans under their icy surfaces, with volumes sometimes several times greater than all terrestrial waters combined.

It's enough to spur NASA on to ensure the launch of the Europa Clipper mission, scheduled for October 10, 2024, without major delay. That is the prerequisite for reaching Europa, the moons of Jupiter, in spring 2031, before the arrival of JUICE (the acronym for Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer), its competitor from the European Space Agency (ESA). It was launched in April 2023, from the Kourou base in French Guiana and is already on course. Taking a less direct route through the Solar System than the American spacecraft, it is not expected to reach the celestial body until July 2032. In principle, too late to win the long-distance duel.

The race is above all symbolic. Successfully negotiating Jupiter's dangerous radiation belts to fly over Europa is a technological feat that teams on both sides would rightly like to publicize. At the end of the day, they will be doing complementary work, and be required to collaborate in this adventure, entirely devoted to the study of those hidden oceans of the Solar System.

By aiming their arrays of instruments at the moons Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, the Europa Clipper and JUICE probes (which will also observe Jupiter) are to characterize two (or even three) of these liquid expanses and attempt to establish whether they could constitute environments conducive to support a form of life, which would draw its sustenance from the exploitation of mineral resources. It would have journeyed the entire evolutionary path without ever having been exposed to light, being limited in terms of horizon to the inner walls of a kind of giant aquarium formed by the ice shell encapsulating its world.

Potentially habitable oceans hidden in icy satellites with external temperatures approaching -150°C? It was time to put this old moon to the test. With so much talk but little evidence, it was in danger of drying out.

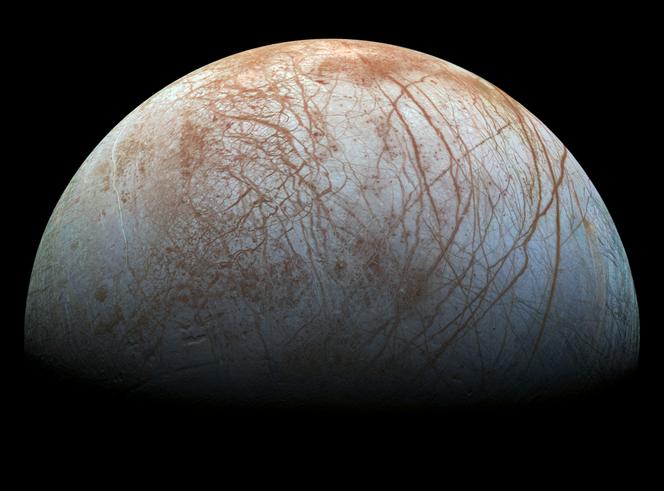

It all began in 1979 with the first hints of tectonic activity on Europa. That year, the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 probes sent back the first images of this large satellite. Astronomers were astounded by what they revealed about the surface. Almost devoid of relief, it is smooth like no other object in the Solar System. And, contrary to all expectations, it is made up of young terrains, sparsely cratered and only 40 to 90 million years old. Everywhere, cracks and stripes similar to those of terrestrial ice sheets crisscross the crust, indicating the renewal of its ice by internal movements initiated at the base of the cap.

You have 81.28% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.