The contrasting fates of Japan's migrant workers

FeatureThe number of foreign workers is constantly increasing in the archipelago, which has a growing need for labor. The satisfaction of those who are better integrated does not disguise many workers' dashed hopes.

Ngo Gia Khanh is a well-built 22-year-old with closely cropped hair. His slightly concerned expression seems to bear witness to the rollercoaster ride he's been on since leaving Vietnam a year ago. When he joined the technical trainee program, allowing Japanese companies to hire unskilled foreign workers, he certainly hadn't anticipated what was in store for him.

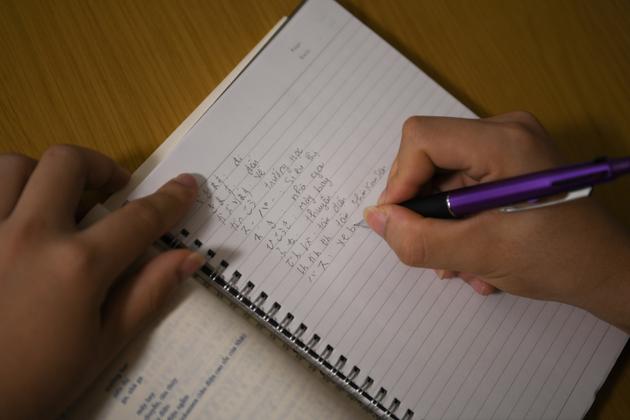

Born in the northern Vietnamese province of Quang Ninh, he had two closely connected goals: "To learn Japanese and forge a career here in Japan." So off he went to Hanoi, the capital, where he set about learning the rudiments of Japanese. Then local intermediaries put him in touch with the Japanese organizations responsible for organizing stays for trainees in Japan, as well as finding them work. In the spring of 2022, he finally arrived in Tokyo.

Khanh quickly became disillusioned: "I'd been promised a job as a bricklayer and ended up scraping cement. I'd been told I'd earn 180,000 yen [€1,144], but I only got 124,000," he said in the office of a support NGO based in a residential area of Tokyo. "With my level of Japanese, I couldn't communicate with my colleagues. I was shouted at by the foreman, and once he even hit me with a metal grater. Another time, a Japanese worker grabbed me by the collar and spat: 'Go back to your shitty country!' I was completely lost..."

Japan's demographic decline is forcing local companies to depend increasingly on foreign labor, particularly in the construction, shipyard and hospitality sectors. At the end of the last century, almost 90 million Japanese were aged between 15 and 65. By 2040, the same age group is projected to decrease to 60 million. As a result, according to a report published by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the archipelago will need 4.2 million foreign workers by 2030. This year, the private institute Recruit Works estimated that the archipelago will face a shortfall of 11 million workers by 2040.

Employers abuse their power

The image of Japan symbolizes dreams of far-off lands and promises of brighter tomorrows for unemployed young people from poor backgrounds in countries across South and Southeast Asia. But this so-called trainee pathway – a reservoir of cheap labor for companies that Khanh has ventured into – is increasingly controversial. It promotes the abuse of power by employers toward foreign workers who face (along with other challenges) the complex cultural codes of a Japanese society that tends to be insular and, for the most part, has remained ethnically homogeneous: The number of foreign residents barely exceeds 2% of a population of 125 million inhabitants.

You have 70.66% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.