The autumn line-up promises to be rich. The Centre Pompidou in Paris is celebrating the centenary of the publication of André Breton's first Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924, with a vast exhibition devoted to this intellectual and artistic movement. Other artistic movements in the spotlight include arte povera at the Bourse de Commerce and pop art at the Fondation Louis Vuitton.

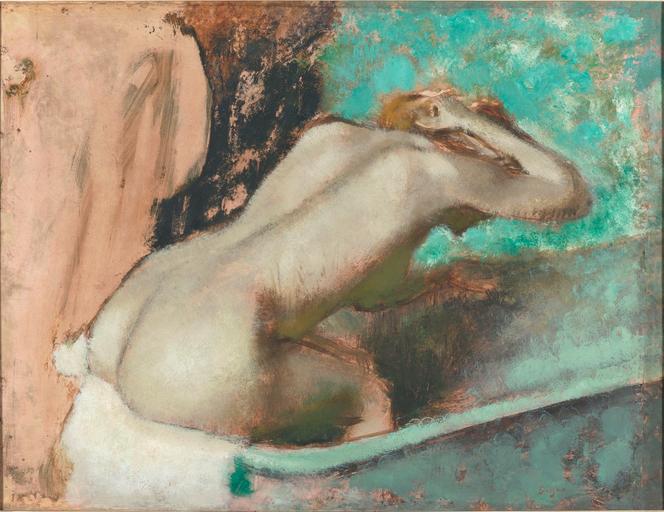

We think of intimacy as a secret garden, a room of one's own, protected from others. Yet moral conventions and social control have governed it for centuries, as illustrated by the dense exhibition "Private Lives: From the Bedroom to Social Media," organized at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs under the general curatorship of its director, Christine Macel and design and architecture historian Fulvio Irace. A rich cross-section of ages and genres, from objects of convenience to the cocoon sofas of the 1960s, from bath scenes by Edgar Degas (1834-1917) to photographs by Nan Goldin or Zanele Muholi.

The question of intimacy appeared in France in the 18th century, with its rosy-cheeked coquettes spied through keyholes. But it was in the following century that intimacy made its mark with the emergence of a middle class that separated family and professional life. During the 20th century, and even more so in the 21st, everything has been in flux: design reflects the tension between the desire for isolation and the need for promiscuity. Social media blurred the boundary between private and public spheres. Precariousness and exile remind us of the difficulty in preserving intimacy when one no longer has a space of one's own.

Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris. From October 15, to March 30, 2025.

In the Middle Ages, fools were everywhere. Not as defined by modern psychiatry, but as the manifestation of ordinary folly: that of all the men – and women – who, permanently or occasionally, in times of carnival, indulged their passions instead of caring for the salvation of their souls.

The Louvre revisits this forgotten excess through more than 300 works of art: a journey into folly as it was understood in Northern European art, revealing a fascinating period that culminated in a few seminal texts, such as Ship of Fools published by Sébastien Brant in 1494, followed, in ironic response, by Erasmus' In Praise of Folly in 1511. Brant opposed both measure and wisdom to the crises of his time. Erasmus, for his part, wondered whether it is not the wise, the reasoners, who are the real fools.

You have 87.39% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.