In February of last year, at an official lunch in Kyiv held for the ministers of culture of both Ukraine and France, the topic of Bulgakov's house, now a well-known museum, came up for discussion. Several of the Ukrainian artists present thought it should be shut down, a position that had already taken on momentum in Ukrainian society. Mikhail Bulgakov (1891-1940), the great author of The Master and Margarita, was born in this house (to an ethnically Russian family) and grew up there, attending an elite Kyiv gymnasium throughout his adolescence. He wrote about Kyiv. But he could not accept the idea of Ukrainian independence, and in his play The Days of the Turbins, referring to the Hetman Symon Petliura's attempts to impose the Ukrainian language, he wrote: "Who terrorized the Russian population with this vile language, which does not even exist in the world?"

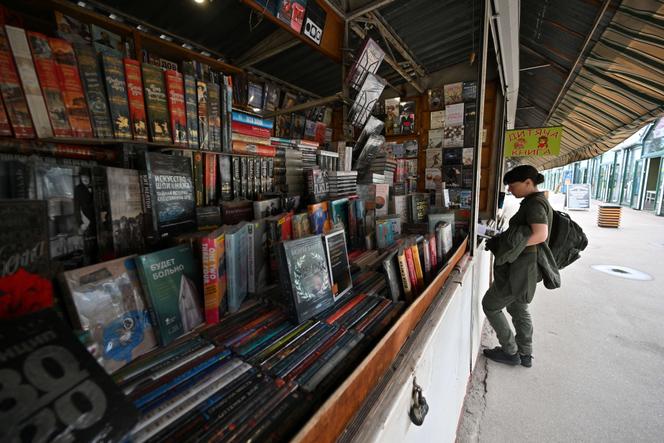

The question of who to consider an Ukrainian writer had imposed itself upon me some months earlier, after the start of the war, when I found myself gazing at my shelves of

"Russian" literature and wondering if I should perhaps separate out the Ukrainians. But who exactly should I consider as an "Ukrainian" writer? What would the criteria be? Language alone would not suffice, nor pure geography, nor even the writer's own opinion. Separating the Ukrainians from the Russians might not only prove a rather tricky process, I realized as I studied various biographies, but also a singularly political one. For the quest to untangle who might be considered an Ukrainian author quickly led me into a rabbit warren of personal histories that reveal much about the nature of empires and their multilingual denizens, of wars and shifting borders, of nation-building and its repression.

But you have to start somewhere, and I started sitting, staring at the spines of books. Novels and poems written in the Ukrainian language would have been the obvious place to begin. But to my great shame I realized I only owned one, a translated volume of collected poetry by Taras Shevchenko (1814-1861), the founder of the modern Ukrainian literary language. There are so many more I have not yet read. Independent Ukraine has produced dozens of marvelous writers, such as Yurii Andrukhovych (b. 1960), whom my late Catalan-language publisher, Jaume Vallcorba, had known well and told me a great deal about; Serhii Zhadan (b. 1974), whose poetry reading I attended in Kharkiv in May of 2022, while the Russians were bombing the city; or Victoria Amelina (1986-2023), murdered last year by a targeted Russian missile strike in Kramatorsk a few days after I shared a stage with her at a literary festival in Kyiv.

You have 77.67% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.