Renault is one of the few French companies that has shaped French people's idea of their country. The connection between the brand and the "national narrative," as essayist Raphaël Llorca called it, is what is fueling the protest against an auction due to be held on June 6 at Christie's in Paris of 33 works from the Renault collection, complemented by an online sale of drawings by Henri Michaux.

"This sale betrays the spirit of the collection; it distorts and disfigures a unique ensemble," railed Delphine Renard after first speaking out in Le Figaro. The psychoanalyst is taking a stand because this collection was created in 1967 by her father, Claude Renard, a senior executive at the then state-owned carmaker. He wanted to bring the world of industry and contemporary art closer together at a time when art was not the tool of distinction and speculation that it has since become.

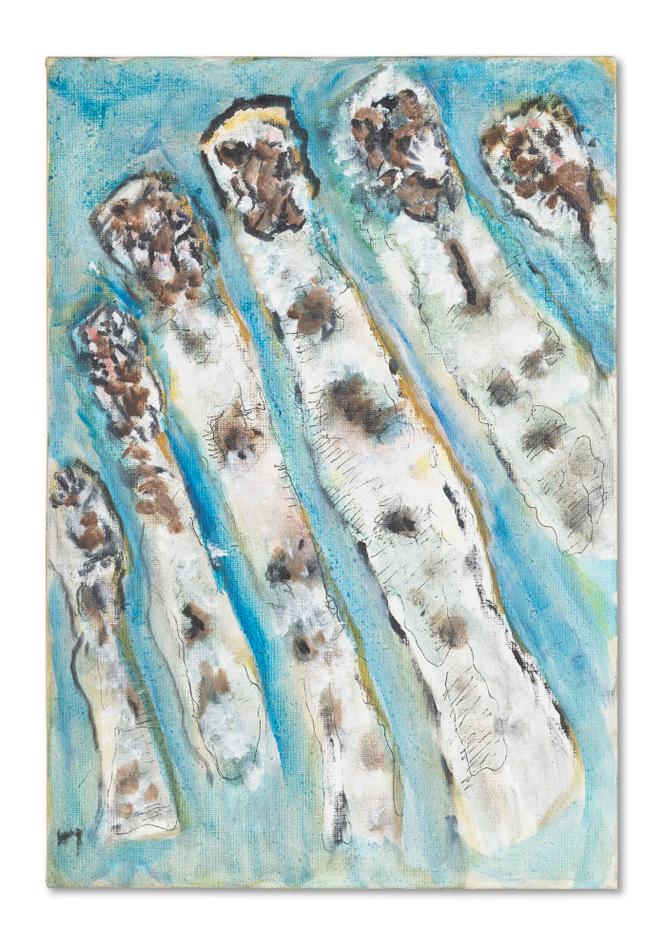

The estates of Jean Degottex, Simon Hantaï and Jesus-Rafael Soto, as well as that of former Centre Pompidou curator Margit Rowell, the legal successor to painter Georges Noël, have joined her fight. "The spirit of this patronage was to form an indivisible collection, which was never to be resold," they protested in an open letter published by Le Monde. Ramuntcho Matta, the son of painter Roberto Matta, five of whose works feature in the Christie's sale, was also outraged "that a flagship of the French economy should sacrifice part of its cultural heritage that was purchased for social purposes."

"For my father, who took me on his shoulders to the Peugeot workers' picket line, Renault was a different kind of company, which treated its employees better," he added. "For him, this collection had a social and political value."

Although they don't have the power to contest the sale's legality, those who saw the collection grow over the years, sometimes with no connection to its core business, deplore the way it's being auctioned off. "It's not very smart to put on the market 30 drawings by Michaux with very low estimates all at once and without a reserve price. It sends a clear message: 'We want to get rid of them; you just need to bend down to claim them,'" lamented Jean Frémon, co-director of Galerie Lelong in Paris, which sold many works to the company. "We sold the works at prices that took into account the fact that this was a public collection and that it wasn't going to be resold."

Bernard Ceysson, the former director of Saint-Etienne's Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art and who now works in the art trade, believes the problem is one of ethics and exemplarity. She regretted "that Renault has completely switched to a private company mindset." The company's capital, which was opened up to the private sector in the 1990s, is now only 15% state-owned.

You have 72.93% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.