Mark Rothko was the antithesis of pop art – he witnessed its birth and had little appreciation for it – and the immediate imprint left by a painting that has more in common with the effectiveness of a poster than with the spirituality of an icon. Whereas a work by Andy Warhol is something you must submit to, a Rothko is something you immerse yourself in. You question it. And sometimes, in a sign that you've gone mad, it answers back... His paintings, especially those from his so-called "classical" period, are dangerous: They have the seductive power and beauty of the devil. When looking at his works, it's important to remember the words of Friedrich Nietzsche, of whom he was an avid reader: "If you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you."

With very few exceptions, such as his 1954 tribute to Henri Matisse – L’'telier Rouge ("The Red Studio") by the French painter, acquired by MoMA in 1949, was one of his favorite works – Rothko never titled his post-war paintings. The best he did was give them numbers, albeit in rarely coherent series. Nor did he define the periods of his work: His"multiforms," the first abstractions he created in 1946, and the last phase of his oeuvre (in the 1950s and 1960s), referred to by art historians under the surprisingly revolutionary term "classic," were conventions created after the fact.

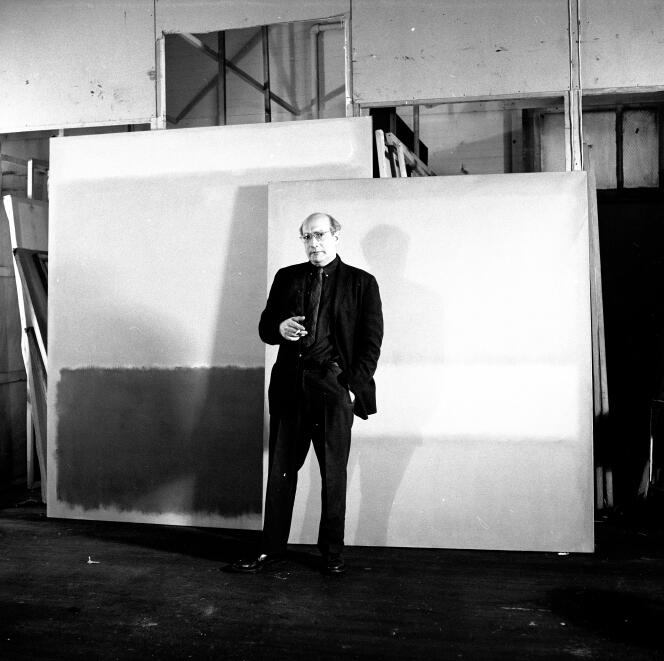

Some also sought to classify him as one of the abstract expressionists who made the New York School of the 1950s such a phenomenon: A famous 1950 photograph by Nina Leen shows him sitting with them. They called themselves the "irascible" because they were protesting against what they saw as the disastrous choice of artists to represent modern American art in an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. All 15 of them stare scornfully into the lens, except for two: Hedda Sterne, the only woman in the group, who has a rather affectionate gaze, and Rothko, seen from three-quarters up, who seems to be elsewhere, as if detached. He felt that his would be a different destiny.

As a matter of fact, he soon became detached, particularly from abstract expressionism, a term he violently rejected. Some painters also rejected him despite having been close friends: In 1955, for example, Barnett Newman (1905-1970) and Clyfford Still (1904-1980) went so far as to write to their shared art dealer, the gallery owner Sidney Janis, to criticize Rothko's work. The wound must have been especially deep as Rothko had worked hard to help Still, who had come from California, emerge on the New York scene, and because Rothko's transition to abstraction owes much to the example set by Still. "The progression of a painter's work…will be toward clarity; toward the elimination of all obstacles between the painter and the idea, and between the idea and the observer," he said in The Tiger's Eye magazine in 1949. "To achieve this clarity is, inevitably, to be understood."

You have 65% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.