Robert Badinter, who abolished the death penalty in France, has died

ObituaryThe intangible, universal vision of human rights held by the former justice minister of justice permeated his writings and opinions until the end of his life. He died on February 9 at 95 years of age.

The commander is dead. The thin old gentleman, whose time-worn figure could have been blown away by a gust of wind, for many years walked slowly, between two conferences, down the paths of his beloved Luxembourg garden, which unfolded beneath the windows of his beautiful Paris apartment. He used to take a short break there to buy a piece of licorice, of which he was very fond of and which was served to him with respect.

The austere Robert Badinter, wearing the armor of the law and a high idea of his mission, softened with age, submerged in memories and countless readings, and walked in the footsteps of his familiar shadows, Condorcet and Fabre d'Eglantine, a stone's throw from the Sénat where he held a seat and whose intricacies he knew very well. Badinter, who will always be remembered as the man who abolished the death penalty in France, died in the night of February 9, at 95 years of age.

'An intellectual in politics'

Badinter, born on March 30, 1928, in Paris, was a Jansenist from the upper bourgeoisie; he was also "republican, secular and Jewish" and not always easy to get along with, and one of the most hated ministers of his generation. With the dust of time settled, he remains the incarnation of a kind of integrity that belonged to the left that the test of power could not divert from its ideals. He spent 30 years as a lawyer, almost five years as justice minister, nine years as president of the Constitutional Council, and 16 years as a senator. He was criticized, not without reason, for having worked for a long time at sculpting his own statue, but he never stopped serving as a conscience. He was "an intellectual in politics," walking in the footsteps of Nicolas de Condorcet, whose fervent biographer he was with his wife, Elisabeth (Condorcet, 1989).

On the evening of February 9, 1943, young Robert entered the building in Lyon where his parents, Charlotte and Simon, had gone to flee the German occupation of the northern half of France. But the Germans were already there. Klaus Barbie, the head of the Gestapo in Lyon, had signed the family's deportation order a few hours earlier. The young man understood immediately, ran down the stairs and melted into the night. Simon, his father, was deported and would never return from the Sobibor extermination camp. Born in Bessarabia, in present-day Moldova, which was then under the Tsarist boot, he had fled the pogroms and then the Bolsheviks in 1919. For him, "a poor, Jewish, revolutionary student," his son wrote in 2007, "France and the Republic were one and the same, mingling the Revolution, the emancipation of the Jews, human rights, Victor Hugo and Zola.

Until 1940, the Badinter family marveled at the extent of the freedom that was offered France, the first country to recognize the equal rights and conditions of Jews in 1791. "You could be a civil servant, an officer, a judge, when it was inconceivable elsewhere," Badinter pointed out. Louis XVI's sister expressed this in a sublime manner when she said, "The Assembly has put the last nail in the coffin of its follies, it has made citizens of the Jews." Badinter often repeated the words of Emmanuel Levinas' father, a Lithuanian rabbi, who, at the time of the Dreyfus affair said, "A country where they tear each other to shreds over a little Jewish captain is a country where one must go." The lawyer judged that "this was a great way of seeing the Dreyfus affair: looking at the bright side, while half the population was devouring the Jews. Levinas always laughed when he said that, but it is profoundly true and, for men like my father, the French Republic was sacred."

The family was viscerally French and patriotic. They talked politics at home. Simon Badinter was a socialist, he took his son 8-year-old son Robert – sitting on his shoulders – to listen to Léon Blum during the Popular Front left-wing coalition that governed France between 1936 and 1938. Simon "spoke French perfectly," said his son, but it was a very literary French, very imbued with old turns of phrase, he spoke a language of the 18th century, which was very chastened, very polite." Robert's mother, "a very beautiful woman," came from Bessarabia, like his father. The two met in 1920 in an unlikely "dance for the Bessarabians in Paris," which always stunned their son: "It's incredible that they met there, when they were born 60 kilometers away from each other in a corner of tsarist Russia!"

In 1943, the boy was not yet 15 years old. His other grandmother was deported to Auschwitz, then his uncle, his father, "and I don't know the number of my cousins," said the old man gravely. "You know, many of my people are on the wall of the Holocaust Memorial." As a young man, he "did not even understand what it meant" to be Jewish, he said in 2018. "It's part of my being. I am French, French Jewish, it is inseparable. It's not a word, it's a lived reality, I lived through the entire Occupation."

A police commissioner gave false identity cards to Robert, his brother and his mother, and the three of them hid in Cognin, an Alpine village that welcomed and protected them. "In those terrible hours, that village was for me France," he later said. "I am convinced everyone knew. Nobody ever said anything. All it took was for one word to get to Touvier and we were dead. Paul Touvier and his militia were in Chambéry, 4 kilometers from us." After the Touvier trial, in 1994, Badinter, who was then president of the Conseil Constitutionnel, called the mayor of Cognin to tell him that he wished to return to the village. "To tell the story. Because I always thought it was very important for children to know that their parents are good people. With such a conviction, a child is better equipped in life." Badinter bought them a Directoire-style "Declaration of the Rights of Man" and signed the back with all his titles. "The mayor was there and I found girlfriends, buddies, who were all, unfortunately, old like me, we fell into each other's arms. 'Ah, Yvette! Ah, Robert!' It was divine, we had dinner, it was June, the weather was so nice." He was made an honorary Cogneraud, a citizen of Cognin, and he was more than a little proud of this.

A deep-rooted sense of injustice

He never wore the yellow star; the family had already left when the order to wear the star was published in the occupied zone. In Lyon, it was not enforced and the Badinter family subsequently changed their identity. He first encountered the judicial system at the Lycée Vaugelas in Chambéry. One of his teachers, a member of the militia, was sentenced to death in 1944 (he was eventually pardoned). Badinter hated the man who had been in the militia, but he admired the teacher and discovered that, during the Liberation, justice, first and foremost resembled revenge. The episode anchored the feeling of injustice in him very deeply.

At the end of the war, as he watched the news and saw the state of those leaving the camps, understood that his father would not return. "I said to my brother: 'Above all, don't let mom go to the movies, try to make sure...' (she went, of course, with a cousin), because I immediately said to myself 'My father is not an athlete, he could never have held on for two years,' it was just impossible. "

In spite of everything, he and his brother went to the Lutetia, the Parisian hotel where the deportees were gathered. "Absence is so obsessive," Badinter explained. "It's a very strange thing, it's a constant fact of being human, as long as you haven't seen your parent dead, it remains an idea, a concept, a pain. But mourning is impossible. For a long time, I dreamed that my father would turn up." Back in Paris, the Badinter apartment was occupied by a collaborator, who refused to give up the place. The trial lasted a year, the young man heard "despicable remarks" about his family and did not get the place back until 1947.

A brilliant student, a hard worker (and an unapologetic ladies' man), Badinter studied sociology and obtained a one-year scholarship to Columbia University, where he met Dwight D. Eisenhower, the future president of the United States. He did voiceover work for actors who were supposed to have a French accent in order to earn a few bucks, and discovered the weight of the law in American society and the firm shield it offers against the excesses of power.

In Paris, he enrolled in law school, and obtained his doctorate in 1952. The young man never forgot his father's orders. "Real life, the only life, was the life of the mind, which is so profound in Judaism, it is the preeminence given to study, to intellectual rewards. The real revenge on prejudice and ignorance was knowledge. It is the only thing that liberates. For men like my father, knowledge and understanding were essential." Moreover, the young Badinter easily pictured himself as a university professor. Teaching for him was "an eternal pleasure," he would do it all his life.

His most vivid memory went back to 1977, the day after the Troyes verdict, where he had saved the skin of Patrick Henry, who was guilty of kidnapping and killing a 7-year-old boy. As he had for the last three years, Badinter entered the amphitheater at the Sorbonne. All the students were standing and they applauded him for a long time. On the blackboard, someone had written, "Thank you, Mr. Badinter." The professor opened his briefcase and said: "Thank you. He was lucky. So am I." And he calmly began his lecture.

A chance entrance to the world of law

In 1950, at 22 years old, he passed the certificate of aptitude for the profession of lawyer and entered the world of law, "by chance, not by vocation." He started out modestly in a lawyer's office, where his job was writing false letters containing break-ups or insults, intended to be used in divorce cases. This was his initiation into what he called "the judicial comedy" and he took a certain pleasure in his role as "a lawyer's assistant." This was when he met Henry Torrès, a formidable baron of the criminal bar, whose voice was "bronze," whose stature was "powerful" stature and whose eloquence was "sublime." Torrès later said that he had never met such an insolent young man, but Badinter was under the spell and very quickly came to call him "my master." "He's in his element in a storm," said Senator Gaston Monnerville about the master. "When Henry Torrès argues, he's like a gigantic lumberjack cutting down the forest."

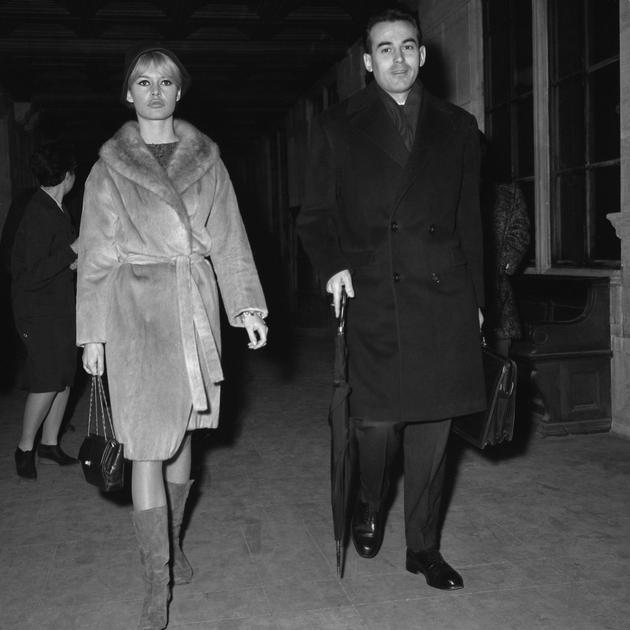

A writer, journalist and lawmaker, Torrès was an old-fashioned lawyer, who both fascinated and irritated Badinter; the young disciple was wary of his conventional eloquence, which sometimes seemed "heavy, old-fashioned, almost old-fashioned" to him. His style was assertive, it belonged to a new generation that used sober, effective rhetoric, and was supported by an in-depth understanding of the files. Georges Kiejman was of the same caliber, as was Jean-Denis Bredin. And when Torrès gave up the job in 1956, Badinter had to find clients. His colleagues, who found him cold and distant, do not care for him very much. (Tt was true that he didn't often say hello to them.) But he had the good fortune to meet Jules Dassin, an American filmmaker who had fled McCarthyism. The director had a problem, but no money, Badinter had talent, but no clients: They immediately came to an agreement. And the lawyer soon prospered in copyright law, then found partners and set up an up-to-date firm where he defended the interests of Charlie Chaplin, Brigitte Bardot, Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, Sylvie Vartan, Coco Chanel, and Raquel Welch who were followed by the magazine L'Express and the publisher Fayard.

In 1955 the young litigator married a pretty actress, known as Anne Vernon, but whose real name was Edith Vignaud. She played the role of the mother of Geneviève (Catherine Deneuve) in Les parapluies de Cherbourg (The Umbrellas of Cherbourg). He divorced her and in 1966 remarried the writer Elisabeth Bleustein-Blanchet. They had three children – including one named Simon.

Bredin, a young man who was 'too well brought up'

In 1966, Badinter joined forces with Jean-Denis Bredin, the first secretary of the Conférence du Stage (a highly respected prize for eloquence at the bar). They both founded a very successful business law firm, with Badinter taking charge of press law, copyright law and corporate law, and Bredin of inheritance and arbitration cases. The firm did not practice criminal law. The two men, both university professors, got along very well and had little in common. Badinter, always filled with a holy passion, was seen as a competitive adventure in the halls of justice, while Bredin was a young man who was "too well brought up," as he titled his memoir, in which he portrays himself as an exquisitely courteous, refined dilettante. On the day the luscious Raquel Welch came to the firm, Bredin did not dare to talk about money, but Badinter took care of it without beating about the bush, not yet having the image of being a frugal Jansenist as he does today.

Along with Bernard Jouanneau, he was also brought in to defend François Mitterrand, leader of the Parti Socialiste (PS), who was being sued for defamation by Charles de Gaulle's nephew, who reproached him for somewhat sharp comments on the Resistance in L'Expansion. Pierre Lazareff, the omnipotent boss of the newspaper France-Soir, introduced them to each other. The hearing took place on February 19, 1973, in other words, before the first round of the legislative elections on March 4. Mitterrand risked being stripped of his civil rights for one to three years. Badinter played for time and spent hours developing a treasure trove of legal arguments. "You won't wear us down," the judge warned him, but he managed to get the trial postponed. "A scoundrel's tactics," complained the judge. Although Mitterrand was ultimately found guilty, it was after the elections. Required to pay damages, he congratulated the young man on having "stopped the judicial machine."

Badinter became close to former prime minister Pierre Mendès France, a photo of whom was still watching over him 30 years later in his office as minister of justice. But he was not a member of the circle of close friends with whom Mitterrand launched the renewal of the left. More personal than political, their relationship became closer later. In 1984, the Mitterrand, then president, asked Badinter to countersign, in the greatest secrecy, the act by which he recognized his illegitimate daughter, Mazarine Pingeot.

Amnesty International and the League of Human Rights

The lawyer was not interested in political games and apparatus maneuvers, even if it was sometimes necessary to bow to them. He was an unsuccessful candidate in the 1967 legislative elections in Paris, and he didn't run again. The years that followed saw the founding of the Parti Socialiste, which would obtain a resounding electoral victory in 1981. Badinter was more at ease in the ranks of Amnesty International and the League of Human Rights. This did not make his link to Mitterrand any weaker. He had the ear of the first secretary of the PS as he would have that of the president, to whom he recommended, in the 1970s, a promising young man named Laurent Fabius, who would become prime minister.

At that time, Robert Badinter, a lawyer, had two faces. The first was the discreet face of a specialist in business law, the second was the flamboyant face of a defender of famous cases. He assisted the families of Judge François Renaud, who was assassinated in Lyon in 1975, and Jean de Broglie, former minister under de Gaulle, who was assassinated under mysterious conditions in Paris in 1976. He also defended André Resampa, former vice-president of the government of Madagascar, who was prosecuted in his country for treason; Klaus Croissant, the lawyer of the Baader gang; Ali Bhutto, the former Pakistani prime minister, who was hanged in 1979; and the socialist trade unionist Edmond Maire, who was accused by the Communist Party of having "pacified Algeria with a flamethrower." The lawyer of politicians was also, on occasion, the lawyer of great criminals. He gained a reputation as the official defender of thugs and his most bitter opponents would shamelessly bring this up when he was appointed minister of justice.

However, Badinter was first and foremost a business lawyer. In his entire career, he only argued in court 20 times, seven times in capital punishment cases in France, and two abroad. But he had a certain understanding of justice, and refined his criticism of the judicial institution following the Algerian war; he was also a determined opponent of the death penalty, having made the fight a personal matter. But this came with risks – 1976 a bomb exploded on the doorstep of his apartment – and even in his own office, some found it difficult to understand why he defended murderers. "Defending," said Badinter, "means loving to defend, not loving those we defend."

In L'Exécution ("The Execution," 1973), a terrible account and a bedside book for generations of lawyers, he told what it was like to defend Roger Bontems, who was sentenced to death in June 1972 in Troyes by a criminal court for complicity in the murders of a guard and a nurse after a hostage-taking at the Clairvaux prison. He had promised his client: "You will get out of this, Bontems." "Are you sure?" "Absolutely." He swore to him that the president would pardon him. Bontems was not the one who had killed, it was Claude Buffet, the other hostage taker. But President Georges Pompidou refused to be swayed and grant a pardon. One early morning in November 1972, Bontems was taken to the guillotine after a last glass of cognac. Badinter was there, in the cold courtyard of the Santé prison. He never forgot "the sharp slap of the blade against the buffer." Neither would his readers. On the other hand, he did somewhat forget his co-defender, the excellent Philippe Lemaire, who is reduced in the book to the simple role of co-worker and who held a grudge for a long time. Badinter wanted people to know that the fight to abolish the death penalty was personal.

This failure made him the man who went on a crusade. The preface he wrote in 1989 to Victor Hugo's Dernier Jour d'un Condamné (Last Day of a Condemned Man) showed to what extent he mixed the fight of those years with that of the writer. "A tireless fighter, he fought against the death penalty in Parliament as well as in the trial courts, in writing as well as orally," an exact portrait. In 1977, in the same courtroom in Troyes, Badinter saved Patrick Henry's head, when he was on trial for the kidnapping and murder of a child. The man, who, in front of the Parisian civil courts, displayed the cold eloquence of a jurist who was sure of his art, became a passionate spokesperson in the criminal courts, making the court and the jurors tremble. On that day, he delivered a defense speech that the day's witnesses would not soon forget – and of which no written record remains, given that Badinter did not write down his speeches. He defended and saved the heads of six convicts. "They will be my witnesses when I appear before the Lord," smiled the old man. "I am a modest sinner, like everyone else, but I have witnesses for the defense, although, for the most part, they are murderers."

The end of the death penalty

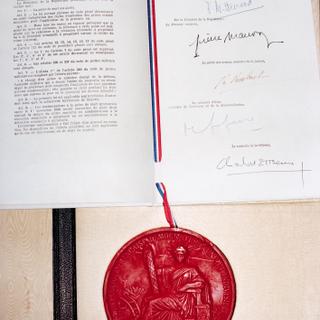

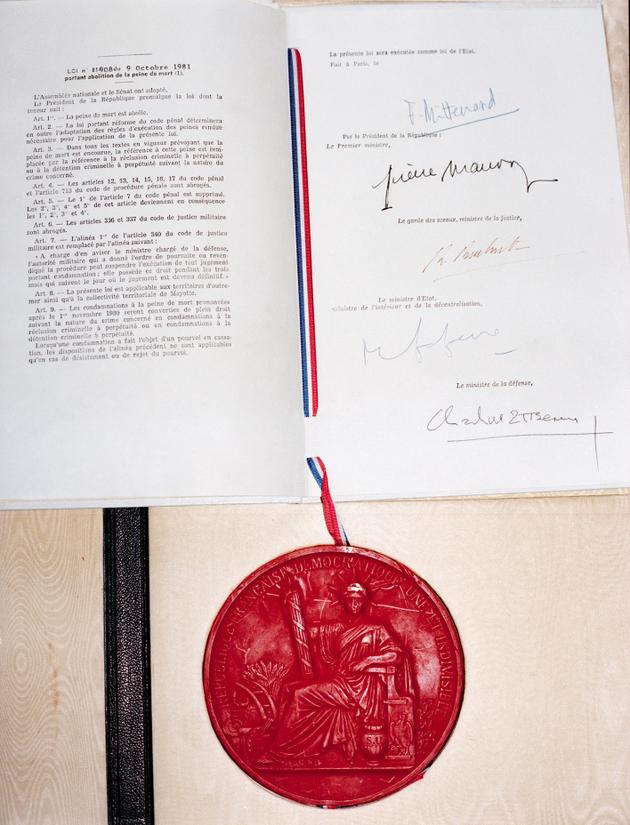

Henry's life sentence did not make up for Bontems' execution. The road was still long until that day in the fall of 1981 when Badinter finally spoke the words of deliverance from the podium of the Assemblée Nationale before a sparse audience: "I have the honor, on behalf of the government of the Republic, to ask the Assemblée Nationale to abolish the death penalty in France." On October 10, 1981, law no 81-908, appeared in the Official Journal. Dated the day before, its first article soberly declared, "The death penalty is abolished." At the time, there were seven death row inmates in French prisons, whose lives were saved.

The old man kept a large black leather notebook, the original text of the law, flanked by a huge seal and hanging from a thin tricolor ribbon. "I wrote the first article, 'the death penalty is abolished,' with my own hand, with so much satisfaction," Badinter said, at 88 years old. We could stop there. All the rest is uninteresting. The following articles serve to remove from the penal code the reference to a punishment that no longer exists. The text is short and the signatures take a whole page. "You will notice, unfortunately, that there is only one survivor left," said Badinter, in 2016, referring to the artisans of the abolition. "All the others are gone. I am the only one left." President Mitterrand, Interior Minister Gaston Defferre, and Defense Minister Charles Hernu all died before him.

After the vote in Parliament, copies of the law – four or five, for the archives – went around the table at the council of ministers, for signature, by the order of protocol. Badinter borrowed a black ball-point pen from his chief of staff, and the signature has now turned a little red with age. When the meeting was over, Mitterrand signaled his minister of justice. "He said to me, 'I wanted to give you something,'" Badinter remembered. "And he took the text out of a folder. I replied, 'Listen, Mr. President.' and he said: 'No, no, it's for you, I know that you worked a lot for it. I know how you love historical documents, as I do. It's for you." Badinter walked out, overcome with emotion, the precious document clutched to his heart. "I am very fond of it, because it is a historical document, but also because it shows the sensitivity of friendship."

There is a curiosity in the law's Article 2. "'The law reforming the penal code will also determine the adaptation of the rules of execution of sentences made necessary for the application of the present law,'" read Badinter. "This means absolutely nothing." They had to slip something in because the socialist lawmakers wanted an alternative sentence no matter what. "I replied: 'Today, we are abolishing, period. We are not putting the penal code in order here, this is the big day, it's the pure, simple abolition, and for me it is definitive. We are not substituting a punishment for a punishment." Badinter added Article 2, whose obscurity charmed him. "I said that I wanted a text, provided that it said nothing. And it doesn't say anything."(Laughter.) I marvel at that article."

In 1981 however, Badinter's important work was not yet recognized. Elected president, Mitterrand wronged him by choosing Maurice Faure, an important figure of the 4th Republic, as his justice minister. The penance lasted only 31 days, the time it took for the socialists to win the legislative elections in June 1981. Badinter was then appointed to the position, and remained there for 56 months, a record only beaten under the Fifth Republic by Jean Foyer, who served for 60 months under de Gaulle. Badinter was dining at the Drugstore Publicis Saint-Germain when an emissary from the prime minister came to bring him the news. In the room where he went to be alone, he paced in long strides, repeating to himself, "We're going to do great things."

Increase in legislative provisions

A task commensurate with his ambitions awaited the son of Simon Badinter, who was raised in the cult of human rights to become an academic nourished by humanist principles and a lawyer of perilous causes. He worked hard, pushed asceticism to the point of being proud that the Justice Ministry had "the worst table in Paris" and worked first to restore public freedoms abused by the 20th century's upheavals. Inherited from the Vichy regime, the offense of homosexuality was abolished. The State Security Court, whose creation dated back to the Algerian war, met the same fate, as did the antivandalism law, which was a disastrous legacy of May 1968. The object of a virulent polemic at the end of the 1970s, the Security and Freedom Law was repealed, after previous justice minister Alain Peyrefitte had asked to bring it in in response to the increase in delinquency.

Badinter may have increased the number of legislative or regulatory measures in favor of victims, but his alleged laxity was a boon for the opposition. The pardon Mitterrand granted on August 15, 1981 to Christina von Opel, a former client of Badinter, caused a scandal. Christian Bonnet, former minister of the interior under President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, said that he was the "reflection" of the "mold of a certain Parisian society." Letters of insults and threats arrive almost daily at the chancellery. One day, far right-wing police officers come to the Vendôme square to shout: "Badinter is a murderer!" Another day, cab drivers processed down the route to his home in the 6th arrondissement to protest in the middle of the night against the murder of one of their own. His police protection was reinforced. He had his gun permit renewed. A politician had been attacked in this way, since Mendès France.

After the exhilarating hours of the abolition of the death penalty and the abolition of the Stae Security Court, Badinter gave the impression that managing the judicial system was weighing on him. He reformed prison medicine, abolished the security wings and improved a lot of prisoners by allowing them to watch television in their cells. But the assessment he drew of his prison work, in a book he wrote in April 1992 on the history of prisons – La Prison Républicaine (Fayard, "Republican Prisons") – was rather gloom:. "Then (in 1983), I was aware of the resistance that met any improvement in prison conditions. (...) Prison thus seemed doomed to overcrowding and poverty, as if there were secret laws that condemned it to remain so." He saw in this an "iron law": in a given society, the living conditions of prisoners cannot improve faster than those of the most disadvantaged on the outside.

President of the Constitutional Council

The reformer that he had succeeded in being for months was nostalgic for teaching and writing. He hardly got heated up when discussing the reform of a penal code that dated from 1810, a long-term work that would be carried out by other guardians of justice, but which he got started. His preliminary draft was welcomed by Mitterrand as "a work of great value" and was adopted by the Council of Ministers on February 19, 1986, the last one Badinter would attend. The same day, he was appointed President of the Constitutional Council, one month before the return of the right-wing to government.

It is with a certain relief and a sense of duty accomplished that the former minister arrived at the Consitutional Council. Mitterrand appointed him to replace Daniel Mayer, who was a former Resistance fighter, former president of the League of Human Rights, who did not finish his mandate but who obligingly agreed to step aside. The cohabitation between the president and the new right-wing majority in Parliament looked thorny. The presence of a loyalist at the head of the institution is a tradition of the Fifth Republic from which Mitterrand did not intend to depart. "The socialists finding jobs for all their friends!" exclaimed Jacques Toubon. "Isn't this what rats do when the ship is sinking?"

Badinter, a passionate jurist, jubilantly squabbled with George Vedel, the Council's other heavyweight. He did not deny his convictions but obviously had to restrain them. He ratified some bills that he would have fought against in opposition. And he censored others that he would have approved in the majority. A card that is always present on his desk said, "An unconstitutional law is necessarily bad; a bad law is not necessarily unconstitutional."

The bills that were both "bad" and unconstitutional delighted him. This was the case for the law which declared that the "Corsican people" are a "component of the French people." The bill came from Pierre Joxe, socialist minister of the interior. The ruling striking it down on May 9, 1991, was primarily prepared by Badinter. The grumbling Elysée and Interior Ministry did not doubt this for a moment. It was an abrupt reminder of the foundations of the Republic, as he was known to do. The Council wrote: "France is (...) an indivisible, secular, democratic and social Republic which ensures the equality of all citizens before the law, whatever their origin." Therefore; "the French people" in the singular, "composed of all French citizens without distinction of origin, race or religion" exists. End of the lesson.

At the head of the Constitutional Council, Badinter did not innovate much; the jurisprudence the Council relied on had already been established for a long time. However, the jurist dreamed of authorizing ordinary citizens to challenge the constitutionality of laws, but this would require constitutional reform, and Mitterrand, bogged down by the cohabitation, had other things to worry about. Badinter had been working on the project for a long time, but he had to wait for the constitutional revision of 2008, which was imposed by President Nicolas Sarkozy, to see the project carried out. Back in 1981, the minister of justice, in the name of the government, had recognized the right of individuals to call upon the Commission and then to the court in Strasbourg in case the European Convention on Human Rights was violated. Badinter wanted to arm individuals against the arbitrariness of the State, which caused some tense fights in 1993 with the majority on the right.

Painful episode

Discovered much later in 2019, a painful episode he never spoke about lingers from his time at the Council. It was examining a bill, during cohabitation, which touched the equality of citizens in regard to penal law and which seemed to him "point out an obvious unconstitutionality." However, on October 3, 1988, the high institution drew up an "unofficial and absolutely secret opinion" for the president, and the only copy was given to Jean-Louis Bianco, who was then secretary general of the Elysée Palace. "Spontaneously, we all tore up the paper that had been used for the session," said Robert Badinter, according to the council archives, "and we, all, kept silent." Secret notices to political friends are not really within the remit of a supreme court. In 1993, the Council also hesitated to censor a text on the control of foreigners that it considered odious, for fear of the reactions. "Or else we had better sharpen our pens to defend the decision by getting out of the duty of confidentiality," said its president. "If we do that, we will be saying what we really feel, namely that these controls are racist." The text was finally determined to be in constitutional, with "strict reservations of interpretation."

But, under his leadership, the council became the pivot of the European constitutional courts. "The Council was too small for him, he enlarged it to his size," said Professor Dominique Rousseau. He went to a greater number of colloquiums and traveled to the East – which was in the midst of a democratic revival – to export French constitutional know-how. He campaigned for the creation of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, and he was known as one of the spiritual fathers. In December 1992, he also initiated the European Court of Conciliation and Arbitration, whose mission, on a continental scale, was to prevent conflicts arising from the break-up of the former Soviet empire. He was the president of it, but the Court was never called upon.

In 1989, the president of the Conseil Constitutionnel was invited by the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to work with Russian jurists on a new constitution. Once the work was finished, he took advantage of the opportunity to go on a trip with his brother, Claude, to Bessarabia, his parents' native land. "I was very surprised," said Robert Badinter, "I thought that Bessarabia looked like Ukraine, a wheat plain. In fact, it looks like Burgundy, with valleys, hillsides and vineyards. Today, it has become Moldavia. A country in the most extreme misery." The two brothers pushed on to Kishinev, where their family fled the pogroms of the early 20th century. Robert Badinter had mixed feelings. "A dead world does not inspire melancholy. The cemetery was devastated, everything had been razed, destroyed, and covered with a new neo-Stalinist architecture of the post-war years, it was sad, uniform, and gray. It all smelled of a world gone by. It was over."

A bit of revenge

Robert Badinter, however, was ultimately satisfied, even thirty years later. The University of Chisinau, the capital, as Kishinev is now known, intends to make him an honorary doctor. "You better believe I accepted. I showed up at the university where the diploma was awarded (which I have somewhere), it was across the street from the imperial high school where my father had studied. An honorary doctorate is indecently flattering." The lawyer endured the avalanche of compliments without flinching and plotted a bit of revenge.

He thought of his father, Simon, who had a talent for studies, and of the rabbi who had said to the imperial teacher, "You should take him to the tsarist high school." Simon was then admitted to the University of Kishinev, still within the limits of the quota: 5% of students could be Jewish, no more. "My father always told my brother and I that story," Robert Badinter remembered. The decades had not soothed his bitterness or his wound. At the end of the year, at the awards ceremony, the principal of the Kishinev high school, a former officer in the Tsar's army, who was always in uniform, said to him: "You are first in Russian, first in French, etc., you should have the gold medal. But since you are a Jew, you won't get it. You can go." If that's what you experience when you're 15 or 16 years old, it's a good way of making a revolutionary!

The new doctor honoris causa made his little speech. "I told them how happy I was that my father had studied in Kishinev, where he had been very badly treated," Robert Badinter said joyfully, "and I explained why, I repeated what the principal said. I congratulated myself, as a French citizen for having been able to help create a satisfactory and more humane rule of law for the Moldavian Republic and I paid homage to my father, who had insisted on leaving in order to have freedom as a possibility, which belongs to all humanity. We cannot say that the applause was as warm as when we arrived." (Laughter.)

In Paris, Robert Badinter was not overburdened. The main mission of the high court was to determine if laws conformed and the work was fairly quiet – the council only rendered an average of eleven decisions per year from 1986 to 1990. Robert Badinter took up the piano again, which he played very badly, completed his superb collection of judicial documents, wrote his book on Condorcet with his wife, and prepared a play on Oscar Wilde, C.3.3. (Actes Sud) – C.3.3. being Wilde's prisoner number when he was convicted in 1895 for homosexuality. It was staged in October 1995 by Jorge Lavelli, at the Théâtre de la Colline, in Paris. "I'm making a late start," joked the lawyer, "I'm a young author on the comeback trail."

A reputation going beyond borders

When he left the Conseil Constitutionnel on March 3, 1995, to make way for another Mitterrandian, Roland Dumas, his reputation as a high-flying jurist spread beyond France's borders. His honors increased and his horizons broadened. He became president of the committee celebrating the 15th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1998). He was also appointed a member of the Ethics Committee of the International Olympic Committee (1999). At first, he thought of returning to his law firm, but to his great surprise, one of the partners was against it. He was 67 years old, too old to take up a job at a university – even though New York offered him one – but he wanted to stay close to his family. What could he do? François Mitterrand suggested the Sénat, mischievously reminding him that it is next door to his house, almost under his windows.

On September 24, 1995, Robert Badinter was elected senator of the Hauts-de-Seine, against a backdrop of conflict, having returned to the Parti Socialiste, which he had abandoned when he was at the Conseil Constitutionnel. He ran against the outgoing senator, Françoise Seligmann, an important figure in the Parti Socialiste, a member of the Resistance and former collaborator of Pierre Mendès France. The department militants voted for him (61%), but the party feminists were rebellious, and Françoise Gaspard, accused him of "everyday machismo." Nine years later, in 2004, Robert Badinter's term in the Sénat ended. Affected by a stroke that alters his vision, he considered retirement, but he recovered and was re-elected, at 76 years old.

In the Palais du Luxembourg, his stature as a man of justice, a master of law, gave him a special place. As a respected member of the law commission, he argued with exact rhetoric for the respect of fundamental liberties, even if, as a minority, he knew that he is unfortunately condemned to "perpetual sterility" and judged his overall balance sheet as "miserable." He was still thin, and his gaze was still as penetrating beneath his bushy eyebrows. His voice hadn't changed much either, sometimes persuasive, sometimes imperious. But he knew that the current winds were in favor of repression. Terrorism, delinquency, illegal immigration. With each project that hardens the penal law, the ministers of the interior and of justice of that time found the socialist senator of Hauts-de-Seine blocking their way: Jean-Louis Debré, Nicolas Sarkozy, Dominique de Villepin, Jacques Toubon, Dominique Perben.

A universal vision of human rights

In the Sénat and beyond, he came to embody the statue of the commander more than ever, with an intangible, universal vision of human rights. This was his mark, it permeated his writings and opinions until the end. In 2002, he came up against Ségolène Royal, who was then minister for the family and children, and wanted to increase the penalties for clients of underage prostitutes. "I find this excessive penalization of morals extravagant! Better to leave this reinforced police force, which would have made Michel Foucault sneer, to the American neoconservatives. His plumb line remained the same, was rarely "politically correct." He opposed the constitutional project on parity (1999), to the great dismay of his political friends, because his voice carried. He justified this stab at the Jospin government in terms that his philosopher wife, Elisabeth Badinter, did not disagree with. "This debate (...) concerns the concept of humanity. That it is composed of women and men does not mean that it is dual (...). Nothing is more precious than universality, which translates the unity of the human species, beyond differences, even sexual ones."

Once again swimming against the current, he argued for the release of 90-year-old Maurice Papon, who had helped out with the "final solution." He knew the horror of crimes against humanity, but he believed that at a certain age "humanity must prevail over crime." The articles he regularly wrote for Le Monde and Le Nouvel Observateur on issues close to his heart like international justice, prisons, the death penalty in the world showed him to be a determined European. He wrote his own draft European Constitution and argued for a yes vote in the referendum of May 29, 2005 (Une Constitution Européenne, Fayard, 2002, "A European Constitution"). He spoke out against Turkey's entry into the Union because he was convinced that it would harm the cohesion of the 25 members. He believed in the Europe of values as he has always believed in those of the Republic.

In the Sénat, Robert Badinter battled against the project to reform of the penal status of the head of state, as proposed in December 2002 by jurist Pierre Avril's commission of the jurist. Two members of the commission were there, the constitutionalist Guy Carcassonne and the lawyer Daniel Soulez Larivière. "But why is he against it?" asked Daniel Soulez. Robert is suffering from NIBM syndrome," Guy Carcassonne replied placidly. "In other words, 'not invented by me.'"

In September 2011, Robert Badinter did not run again, a bit moodily – his seat was reserved by the PS for an ecologist. He took the opportunity to get started on "a project he'd imagined a long time ago:" the Corpus Consultants firm, composed of 13 professors, high-level jurists consulted on the most advanced points of law. At the same time, he was working on an opera, inspired by an obscure novel by Victor Hugo, Claude Gueux, the story of a silk worker from Lyon, who was arrested in the 19th century on the barricades while protesting against the installation of English machines. Claude was locked up in Clairvaux, "a jail that crushed men, killed them, like a monster." He fell in love with another prisoner and this passion led him to the scaffold. Robert Badinter, always meticulous, consulted the archive file and realized that Hugo had taken some liberties with the historical character. He gave his own reading of it, with music by composer Thierry Escaich, and with a staging by Olivier Py, at the Lyon Opera in March 2013.

In June 2015, with his old friend the lawyer Antoine Lyon-Caen, the former keeper of the seals also published Le Travail et la Loi (Fayard, "Work and the Law"), a text which proposed to reform the labor code. The authors were particularly critical of "the increasing complexity of labor law." For them, "the labor code is meant to be protective and reassuring. Over the years, it has become obscure and worrying. This collective anxiety hinders hiring. The work was received coldly, perhaps because it favored employers.

'When you've seen the guillotine up close, your opinion on the death penalty changes'

However, the death penalty remained Robert Badinter's main concern. In March 2010, he mounted an incredible exhibition at the Musée d'Orsay, Crime et Châtiment ("Crime and Punishment"), which he had been working on for ten years and which presented, among a thousand other horrors, the last guillotine used in France, under the heading of a quote from his beloved Hugo: "When you have seen the guillotine up close, your opinion on the death penalty changes." Badinter has accumulated a gigantic collection of rare and precious documents at his home: small guillotines cobbled together by inmates as well as the original plans of the prison of La Santé, which he promised to bequeath to the Place Vendôme after his death. "I am unfortunately inexhaustible when it comes to history," admitted the former minister, pulling out a copy of the moving handwritten will of Louis XVI, written in the Temple prison. "I have always had a lot of tenderness for Louis XVI," said Robert Badinter. "He was not made to rule, but he was a good man. He had all the virtues of a good family man. Moreover, he was a cuckold."

He also has the decree condemning the king, on January 20, 1793, and the order of execution of the last keeper of the seals of the monarchy, Marguerite-Louis-François Duport-Dutertre, signed by the hand of Fouquier-Tinville. The unfortunate minister had protested against "the horrible spectacle of beheading with an axe" and he ended up on the scaffold on November 29, 1793. "One has less chance of being guillotined when one is a keeper of the seals," Robert Badinter rightly pointed out. The lawyer collected all this "interesting junk" by spending time in the old legal booksellers, near the parliaments of Douai or Rennes, which formerly rendered justice before becoming the seat of the courts of appeal. "There were old documents everywhere," the old man said, "I should have bought everything in bulk. It's all very rare now."

But he didn't have enough space. The books, souvenirs, framed manuscripts have taken over the large office, ahead of the heavy, slightly faded, purple curtains, the Empire carpet, the contemporary paintings, the antique furniture. In the salon, he had all the seals reproduced (at his own expense, he insisted), from the monarchy to the present day. Between a drawing by Plantu and the "one" by L'Aurore with Zola's "J'accuse" of Zola two spoons also sit on a shelf, rather modestly. Large, very simple metal spoons that are tired, worn by life. One comes from Auschwitz II-Birkenau. The other was given to him by the curator of the Rivesaltes camp, created in 1938 in the Pyrénées-Orientales for the administrative internment of "undesirable foreigners."

A Pilgrimage to the past

From the high windows of his office, Robert Badinter was catching a lingering whiff of summer wafting up from the Jardins du Luxembourg as he mechanically played with one of the spoons. "The Rivesaltes curator explained something I had never thought of," said Badinter, after a moment's reflection. "He said, 'You know, the spoon is the man. A spoon is what leaves a man with a remnant of humanity in a camp.'" Everything is liquid in a camp. They serve soup, a few vegetables, pieces of meat on good days. "To eat soup, you can only suck it up, like a dog," explained the former minister. "Whereas if you have a spoon, you can bring the soup to your mouth. You are still a man. That's what human dignity is all about. Since then, I've had a special regard for spoons."

At almost 93 years of age, in 2021, Robert Badinter published a new book, Théâtre I (Fayard "Theater I) – Théâtre II ("Theater II") is in the process of being written – and three plays that he would like to see performed. One is about Pierre Laval's dialogue with René Bousquet on the eve of his execution (Cellule 107, Cell 107), inspired by the two men's trials, which Badinter knows very well; the second is about the Warsaw ghetto (Les Briques rouges de Varsovie, "Warsaw's Red Bricks") – he has two of these bricks, brought back from the ghetto in 1956, on a shelf in his home. And the third is C.3.3. on Oscar Wilde, which he already published in 1995.

His perhaps most personal and touching book is Idiss (Fayard, 2018), the story of his immigrant and illiterate grandmother, whom he knew very well. The little book is indeed touching, and ultimately very dark, haunted by death. The Bessarabia of his parents and grandparents "is a dead world," acknowledged Robert Badinter. "The world evoked in these pages is a dead world, strictly speaking. There is nothing left of it. Dead, assassinated. Hitler wiped out Ashkenazi Judaism, whose sources were to be found throughout the Yiddish world, from the Baltic to the Black Sea."

But the pilgrimage into his grandmother's past did him good. "By going back to her, in a way, I was going back to my own lost childhood, which her memory helped me to revive," the old man. "I am what you call a worker, not at all inclined to idleness, and I said to myself, 'But what are you doing here? There are very important matters right now.' Well, no, and that's where I saw the effect of time passing. I wanted to. Finally, I said to myself, 'This is so stupid.' And I made this book, it was stolen time and, at the same time, it was delicious."