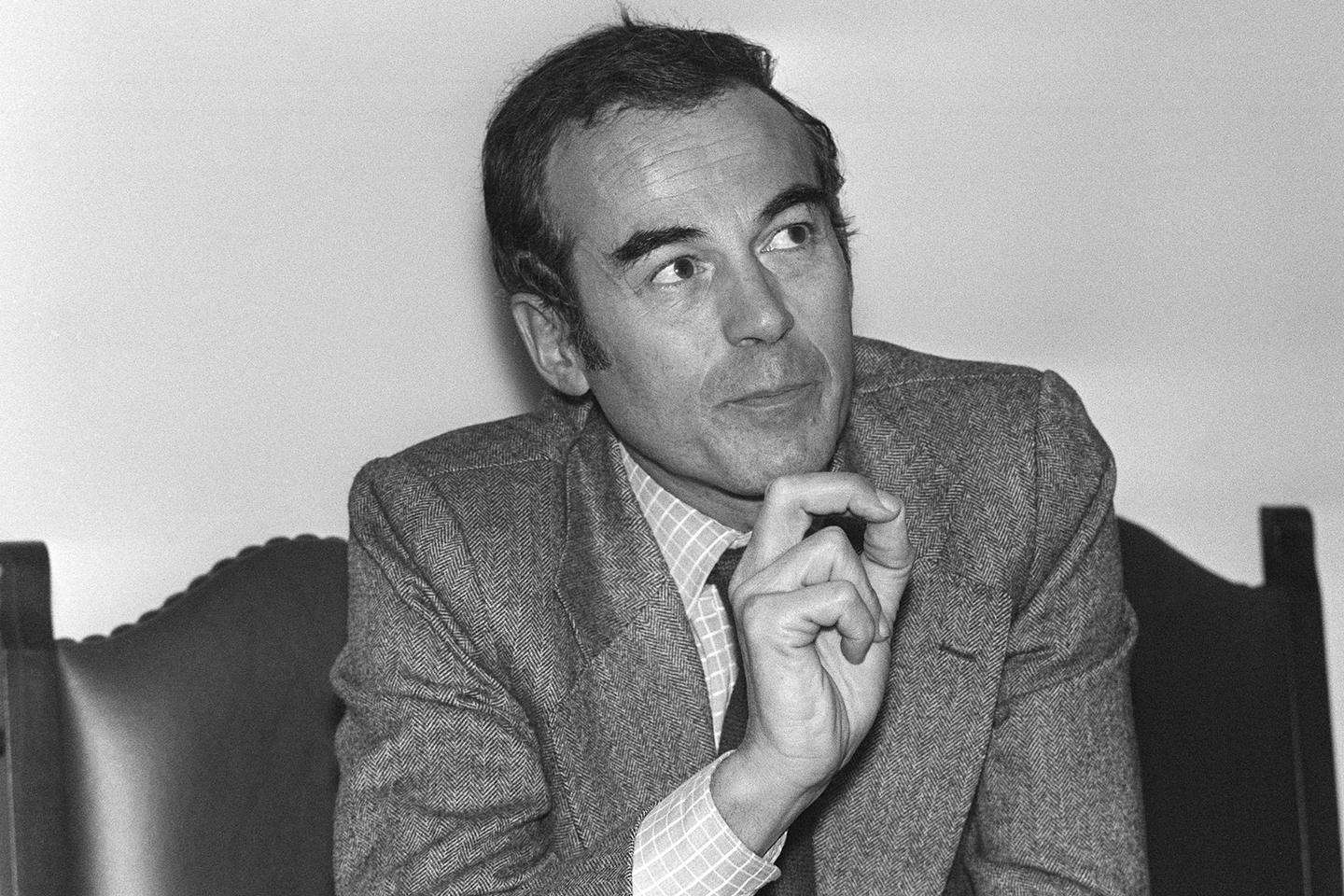

Few men embody the universality of human rights, the defense of civil liberties, and a certain idea of justice and the Republic as clearly during their lifetime as Robert Badinter, who died on the night of February 9, aged 95. If the abolition of the death penalty – the battle of his life, won in 1981 – will remain attached to his name in the history of France, it is because the idea was highly controversial at the time, and by no means a foregone conclusion, even after the election of President François Mitterrand.

A great figure and conscience of the progressive camp, the former lawyer turned justice minister – the most hated minister of the Fifth Republic – and later president of the Constitutional Council, also embodied the left's attempts to apply the human rights proclaimed in the Republic's founding texts to every citizen. "France," he often repeated, "is not the nation of human rights, it is the nation of the Declaration of Human Rights."

Badinter's belief in the need to constantly fight to bring reality closer to the universalist ideals he defended, but which were always under threat, was undoubtedly inherited from his father who fled the pogroms in Bessarabia, a man for whom France was synonymous with the Republic, the Republic that emancipated Jews through the Revolution, the Republic of human rights. Badinter probably also drew his strong beliefs from the shock of the persecution of Jews under Vichy, which led to the murder by the Nazis of part of his family, including his father.

The need for checks and balances

Long a lawyer for politicians and celebrities, the hard-working, ascetic, and self-confident middle-class man fortified his abolitionist beliefs by defending murderers. The horror of the "sharp slap of the blade of the guillotine" in 1972, at the execution of Roger Bontems, whose head he had failed to save, gave him the strength to confront the supporters of the death penalty and to have its outright abolition voted into law in 1981, shaping his stature as a just man for posterity.

But his time at the Ministry of Justice is also to be applauded for the adoption of a multitude of laws reinforcing the rights of many individuals, from the abolition of the "offense of homosexuality," in 1982, to the authorization granted to prisoners to watch television, to citizens' right to a direct referral to the European Court of Human Rights.

A reminder of Badinter's convictions on the need for independent checks and balances, his intransigence on the rule of law, and his anger at the way "man-grinding" prisons operate, seems salutary at a time when the current interior minister is pitting politics against law, the role of the Constitutional Council is being challenged, and prison overcrowding is reaching worrying records.

The righteousness of the former justice minister, his intransigence and stoicism in the face of attacks from the far right, his dogged defense of universalist and European values, his ability to choose the right battles and win them, can only inspire the left, which is still struggling to recover from the ordeal of governing. But it is undoubtedly the intense strength of conviction of a great man worthy of the Pantheon, the coherence of his battles with his personal, professional, political and intellectual itinerary, that everyone will retain as the legacy of the great French conscience that was Robert Badinter.