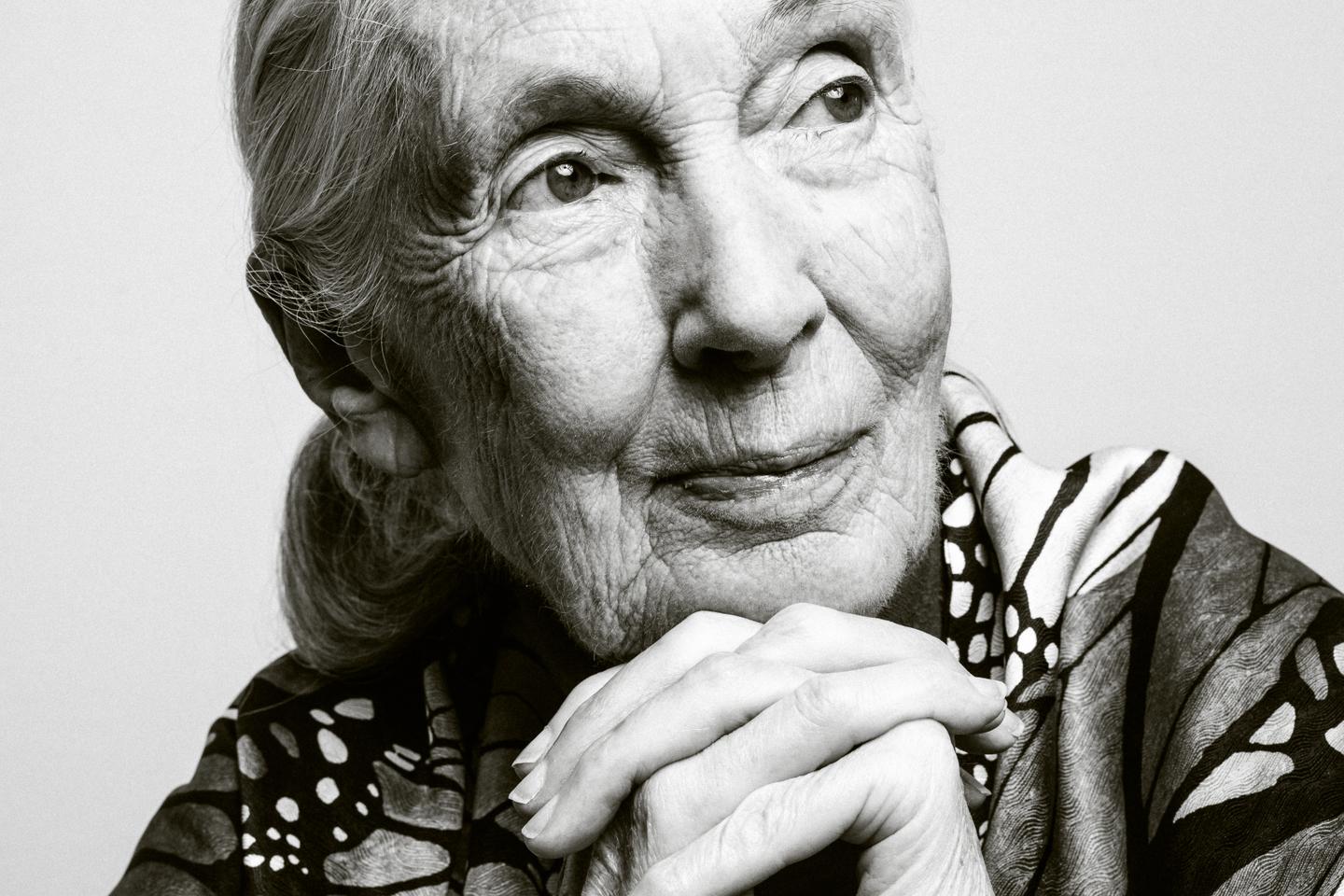

A pioneer of modern ethology and a tireless ambassador for wildlife protection, British researcher Jane Goodall died in Los Angeles on October 1, 2025 at the age of 91. As a little girl, she saw herself as a man in her dreams. The child who aspired to work with animals in a distant country had already understood that this type of freedom was not a woman's business. How could she have guessed that primatology, thanks to her, would become just that? That her observations in Tanzania would revolutionize the way we look at chimpanzees, and consequently, at our humanity?

Her first good fortune was undoubtedly her mother, a woman who never got "angry" and who did not tell her that she was "just a girl" when Goodall confided her ambitions to her. The second was that she did not go to university after high school. Born in London on April 3, 1934, the daughter of an engineer and a housewife (and later a novelist), she could not afford a lengthy education. After completing a secretarial diploma, she worked a series of odd jobs. In 1957, a friend invited her to Kenya, where she met the Kenyan and British paleontologist Louis Leakey, a renowned researcher who was conducting excavations in the Horn of Africa. He hired her as a secretary and, as a result, changed the course of her life.

Leakey, who had not yet discovered our prehuman ancestor Homo habilis, was trying to obtain a grant to study wild chimpanzees. Convinced that wild chimpanzees could shed light on the behavior of early humans, he was wary of conventional wisdom and wanted to send into the field a mind untouched by scientific theory – preferably a woman, who he thought would be more attentive to detail and more empathetic. Impressed by the observational skills of his assistant, whose passion for animals he knew, he offered her this unprecedented mission. In July 1960, Jane arrived with her mother at the Tanzanian site of Gombe, on the shores of Lake Tanganyika. She was 26 years old.

You have 79.55% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.