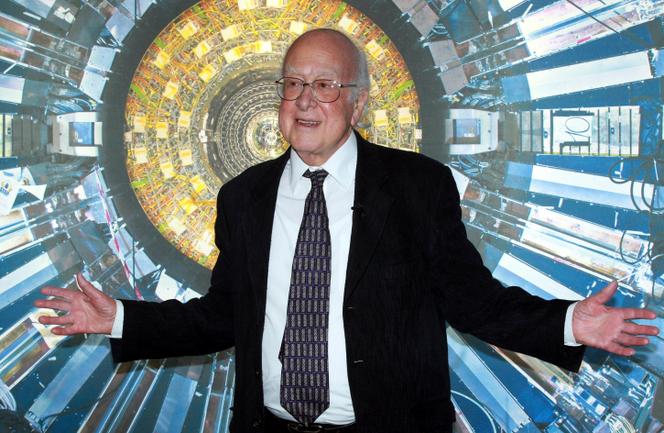

Why do objects have mass? British physicist Peter Higgs, who died on April 8, 2024, in Edinburgh (Scotland) at the age of 94, following "a short illness," according to the University of Edinburgh, will go down in scientific history for having helped answer this question.

In 1964, he postulated the existence of an elementary particle, the boson − a sort of missing piece in the "Standard model" that explains the laws of the universe. He had to wait almost half a century for the construction of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, based in Geneva, to see his intuition confirmed with the discovery of the famous boson, announced on July 4, 2012. The very next year, he was awarded the most eagerly anticipated and fastest-awarded Nobel Prize in Physics, along with Belgian François Englert, in Stockholm.

"If this particle didn't exist, I wouldn't understand a thing!" he said in an interview with Le Monde in 2008, just as CERN's experiments were ramping up. Four years later after being invited to witness the announcement of the discovery, he expressed joy that it had taken place "in [his] lifetime." Englert mourned the death of his fellow countryman Robert Brout (1928-2011), with whom he also described the elementary particle in 1964, just a few months before Higgs. This particle would eventually bear the name of Higgs alone.

Discovered as the first elementary particle since 1994, the Brout-Englert-Higgs boson, observed with a 99.9999% certainty, filled the final gap in the Standard Model, completing the framework of the 16 particles and three forces that form ordinary matter. At around 125 GeV (gigaelectron volts), its mass is 133 times greater than that of the proton.

The Higgs boson is the "glue" that enables particles to interact with a field − one that was independently hypothesized by three theoretical physicists − to acquire mass. It appears fleetingly in proton collisions close to the speed of light, in the 27-kilometer-long particle acceleration tunnel at CERN.

Born on May 29, 1929, in Newcastle upon Tyne, Higgs, son of a BBC sound engineer, was raised primarily by his mother. At high school in Bristol, he became fascinated with the work of a former pupil, Paul Dirac (1902-1984), one of the founders of quantum mechanics. Accepted into King's College London, he excelled in physics, and in 1954 defended a thesis entitled "Some problems in the theory of molecular vibrations."

His first academic position took him to the University of Edinburgh, where he spent most of his career until his retirement in 1996. He once admitted to the Guardian that given his disputes with the institution's administration and his low scientific productivity, he felt he was only tolerated there for fear of ostracizing a potential Nobel Prize winner. He said he was convinced that he could never have made a career in today's hyper-productive world of science.

You have 53.23% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.