One Beninese and one Angolan: These were the only African artists represented – among the 156 men and women – at the Grand Palais in Paris for the exhibition "Art brut. The Decharme donation to the Centre Pompidou". Eight works (four by each artist) out of the 402 on display through September 21.

"Outsider art is outsider art and everyone understands that perfectly well," said painter Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985) in 1947, who coined the term and amassed a significant collection. This movement does not belong to the fine arts, nor is it necessarily shown in the usual venues dedicated to artistic creation, such as art schools or studios. It escapes artistic movements and stylistic influences. It refuses to be boxed into any category and resists all attempts at definition. It exists "elsewhere."

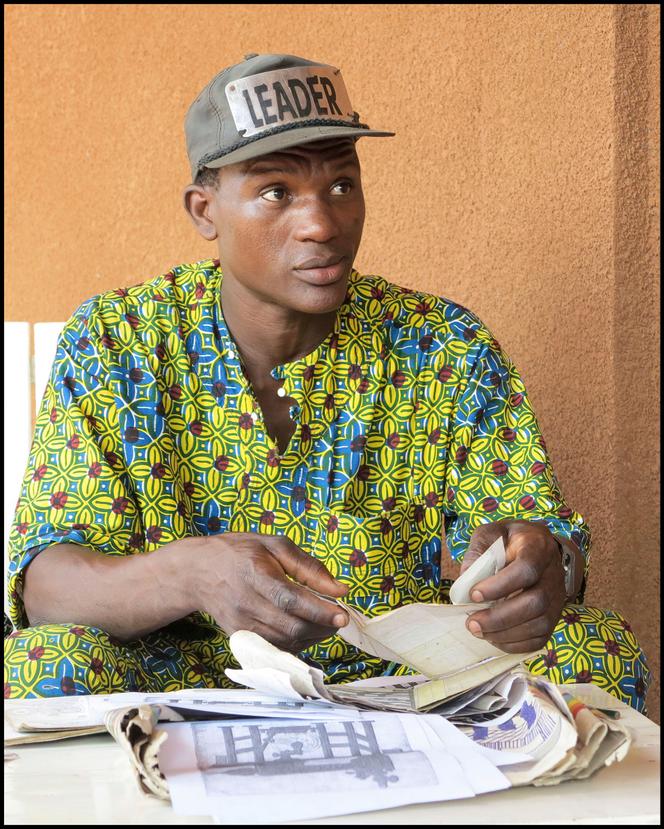

Ezekiel Messou was born in Benin in 1971. A less-than-diligent student, he fled an authoritarian father – a significant religious figure in his village – and settled in Nigeria at age 16. From 1990 to 1995 in Lagos, he learned to repair sewing machines. Upon returning to Benin, he continued to live and work in Abomey, a city in the south of the country, where he opened his own sewing machine repair shop.

In the back room, on school notebooks and A4 sheets of paper, he cataloged models of sewing machines. His early drawings took on the rigid style of technical diagrams. Gradually, Ezekiel Messou adopted representations reminiscent of a bestiary with plant-like curves. Once the drawing was finished, he stamped it with his workshop seal, "Ets qui sait l'avenir. Le Machinistre" ("Est. who knows the future. The Machinistre"), which, according to him, certified his authorship. A form of copyright: "No one can steal my drawings."

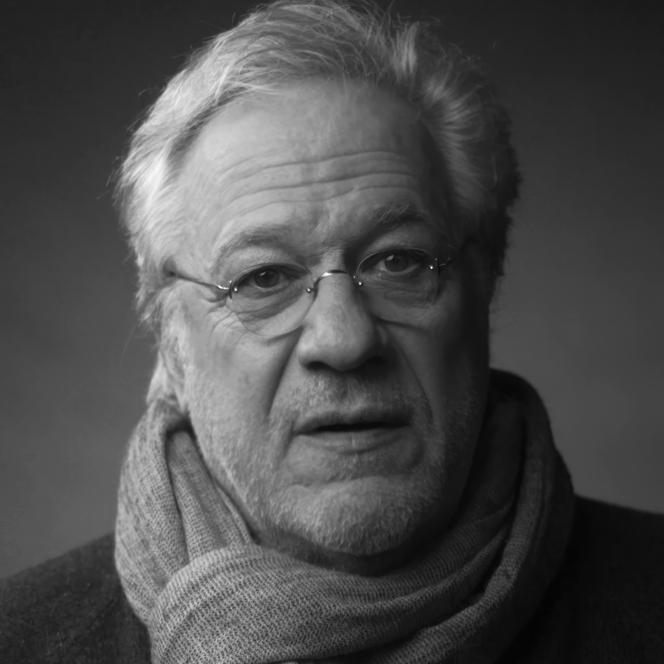

For Bruno Decharme, collector, filmmaker, and co-curator of the exhibition, "Many outsider artists are outcasts, exiled in a psychic reality splattered with stars, who feel invested with a secret mission. Solitary prophets, strangers to the art world and its teachings, outside the norm, they accumulate, decipher, draw, build, and organize a universe whose geography, structure, and forms they invent."

For him, outsider art is "a kind of toolbox, a useful notion for looking where art history has rarely chosen to look. Observing the ever-evolving margins from which the most inventive works of these uniquely styled artists emerge."

The defining moment came in 1976, with the discovery of the collection donated to the city of Lausanne by Dubuffet, who began his "prospecting" in Swiss psychiatric hospitals in 1945. At that time, Decharme was studying philosophy, with professors including Gilles Deleuze and Michel Foucault, as well as psychoanalysts Jacques Lacan and Félix Guattari, who "at that time, were deconstructing the structures of Western societies, decoding and challenging ideological norms."

He emphasized: "I found in the works of outsider art artistic answers to questions I had explored in philosophy – a relationship to otherness, but also to mystery and the unseen. These works, which bear witness to a savage freedom, profoundly changed my life."

So why are there so few works by African artists? Primarily present in Western societies, which have developed a reflection on the margins, and the concepts of dissent or even madness, outsider art in Africa "probably corresponds to different notions than those found in our ways of thinking," explained Decharme. "But that does not mean that these cultures lack artistic expressions bearing witness to otherness. To discover them, it seems to me that we would need to conduct explorations using a different interpretative framework. Research is therefore complex."

The second African artist represented at the Grand Palais comes from Angola: anonymous, nothing is known about his life. His four drawings were created on the back of medical forms and were discovered in a village in Angola before being acquired by the French gallerist, collector, and art dealer Charles Ratton (1895-1986). On December 10, 1944, Dubuffet visited him and was captivated by these delicate works. He acquired one, possibly two, for the outsider art collection he was just beginning to assemble.

The exhibition is designed as a gigantic kaleidoscope. From space to space – "Réparer le monde" ("Repairing the World"), "De l'ordre, nom de Dieu !" ("Order, for God's sake!") "Autour du monde" ("Around the world"), "Chimères, monstres et fantômes," ("Chimeras, monsters and ghosts"), "Danse avec les esprits" ("Dancing with spirits"), "Epopées célestes" ("Celestial epics") and more – visitors are invited to enter each artistic universe. A video feature in each section highlights the importance of these themes and recounts the meeting of the two curators (Decharme and Barbara Safarova, essayist, lecturer at the Ecole du Louvre, and researcher) with certain artists, like a travel diary.

In 2021, Decharme, whose collection numbers over 6,000 works, donated 1,000 of them – produced by 242 artists – to the Centre Pompidou, thus contributing to the creation of an outsider art department previously lacking at the Musée national d'art moderne.

"Art brut. The Decharme donation to the Centre Pompidou" at the Grand Palais, Avenue Winston-Churchill, 75008 Paris (the exhibition entrance is on the right when facing the building's main façade). Through September 21, 2025.

Art brut, exhibition catalog (304 pages and 650 illustrations + 2 inserts for chronology and biographies, co-published by Grand Palais RMN/Centre Pompidou, €45).

Translation of an original article published in French on lemonde.fr; the publisher may only be liable for the French version.