Why do some nations experience stronger economic growth than others? It's a question that has dogged economists − and not only them − since the birth of this field, not least its founding father, Adam Smith, with his famous foundational work, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776).

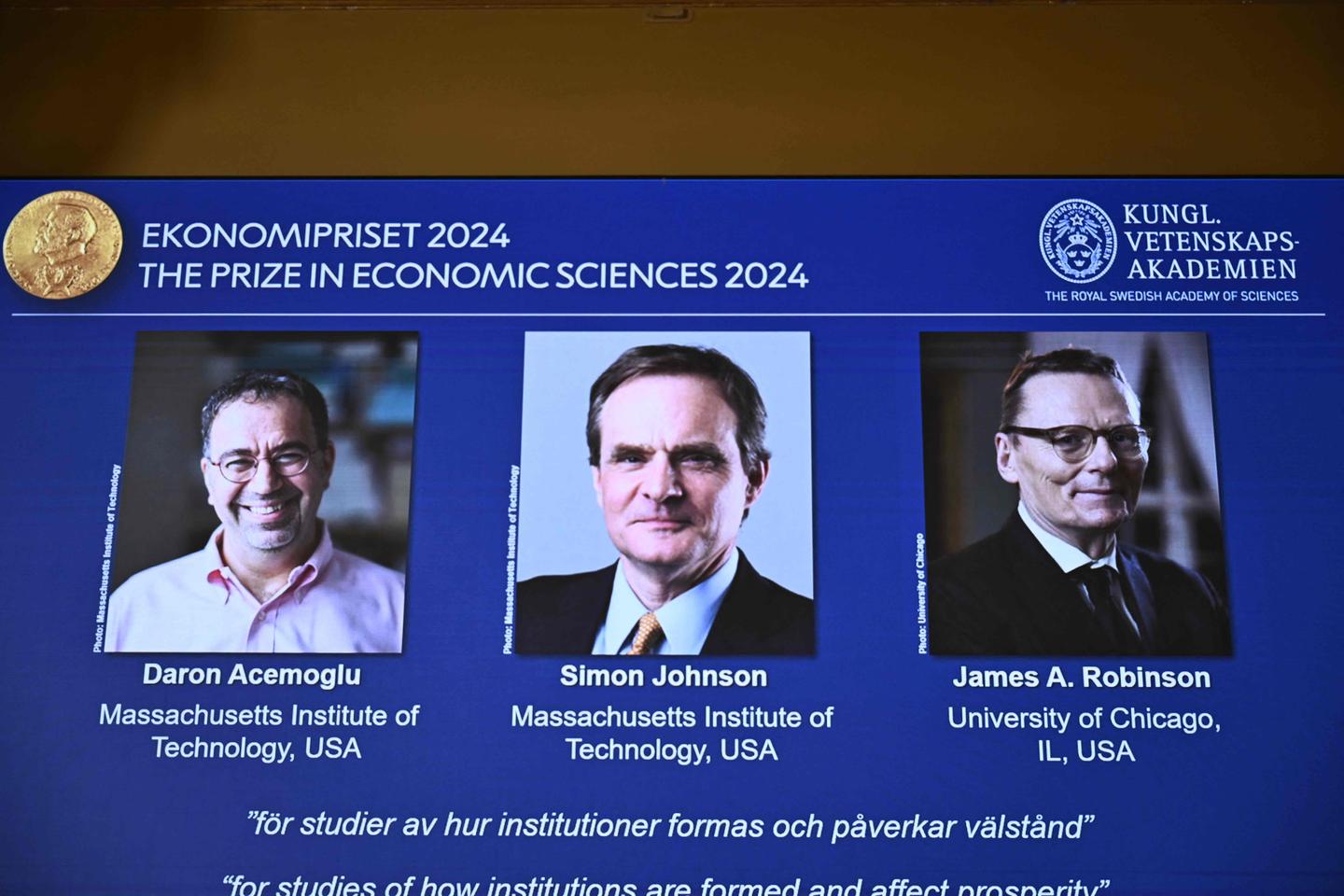

Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson were awarded the 2024 Bank of Sweden Jury Prize in honor of Alfred Nobel (known as the Nobel Prize in Economics) for their own answers to this question, 23 years ago, in an article that became one of the most cited studies in economics: "The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development" (American Economic Review no. 91, 2001).

The three authors − who, although of Turkish and American nationality in the case of the first, and of British origin in the case of the other two, have all spent their entire careers in the US − compared the mortality rates of White settlers in different colonies with the current growth rates of the nations that derived from these colonies. "They concluded that wherever settlers were able to populate − thanks to a less harsh disease environment − large territories, they were able to create institutions capable of guaranteeing rights − particularly property rights − and stimulating technological and economic progress. Whereas wherever this environment was unhealthy, they made do with enslaving the local workforce or importing them to exploit local resources, whether agricultural or mining, in order to extract income," said Philippe Aghion, professor at the Collège de France, by way of explanation.

But in other cases, as the same authors showed in an article published the following year, notably about the southern US in the mid-19th century ("Reversal of Fortune," Quarterly Journal of Economics no. 117, 2002), the institutions that had ensured development became a liability when the economic environment changed − as when the plantation economy came face to face with the Industrial Revolution.

Taking institutional realities into account

Subsequently, the authors applied this approach to other fields. In particular, Acemoglu showed how technological innovation can either redound to the benefit of a dominant elite, or be put into the service of the greatest number of people, depending on the nature of the institutions in place. Johnson used the same approach to analyze the overtaking of the American financial system by a narrow banking elite, and the financial crises this triggered.

The first two winners popularized this approach in the widely read book Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (2012). But above all, the method ushered in a spectacular flowering, in mainstream academic journals, of articles concerning so-called "persistence studies," economic studies that take into account the history and institutional realities of the economies under examination. This has presented a stark contrast to the near-exclusive domination of papers explaining growth through the application of mathematical models.

You have 40.2% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.