It was a historic, landslide victory for Claudia Sheinbaum. On Sunday, June 2, according to preliminary figures, the presidential candidate for the left-wing Morena party, won almost 60% of the vote – against almost 30% for her right-wing opponent, Xochitl Galvez. Sheinbaum's triumph is even more clear-cut than that of 2018 by the man she has pledged allegiance to and will succeed, the current Mexican president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (known as "AMLO").

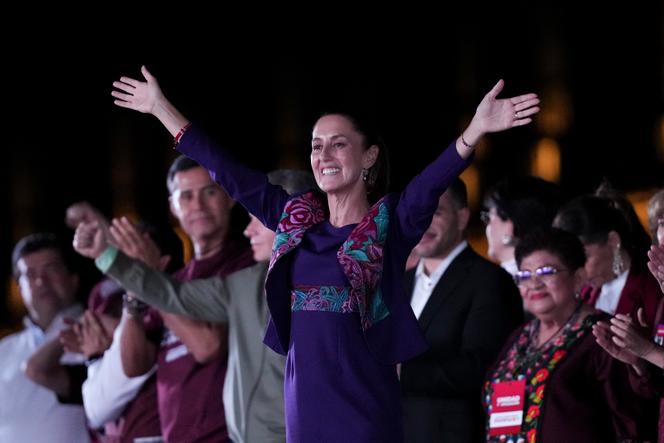

Standing in front of a Mexican flag, the politician who will become the first woman to govern Mexico repeated on Sunday night somehting she has said often: "I'm not coming here alone, but with all Mexican women." In the Zocalo, the country's largest public square, her supporters, who had been gathered for hours, were joyful. During her campaign, Sheinbaum showed a more relaxed side than the rigidity she had previously displayed in public. But, according to her aides, she will run the country in the manner in which she has always worked: hard-working, rigorous, dedicated to her mandate.

When Le Monde asked her in April how she felt after months of campaigning, rally after rally, she replied after a moment's reflection: "I've learned a lot, seeing the enthusiasm of the people for our transformation. I realized that people everywhere believe in us." Sheinbaum differs little from her predecessor, almost always using "we" to talk about their movement, "this principle of humanism that guides us: for the good of all, the poor first."

There has never been a divide between AMLO and the woman he first met in early 2000, when he had just become mayor of Mexico City (a position he held until 2006), and needed someone with a technical profile for the role of environment secretariat. The name of a scientist whose heart was on the left was mentioned to him. Their meeting in a café was quick and the new mayor got straight to the point: "I want to improve air quality, but I don't know anything about it, can you do that?"

Sheinbaum was 38 at the time and a professor and researcher at the Institute of Energy Engineering at the University of Mexico (UNAM). She and her family had spent four years in the US, where her husband, Carlos Imaz, had begun a doctorate in political science at Stanford, and she was writing her dissertation, joining the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, where she specialized in energy.

When they returned to Mexico in 1994, they settled south of the capital, in Tlalpan, a village that was swallowed up by the megalopolis, where the president grew up as a child. "My life began with taking the two children to school in my Volkswagon Beetle and the stress of arriving late to pick them up. Then classes, writing articles, academic life and very little politics," she recounted in the documentary Claudia, directed by her son. Social commitment, however, has always been a part of her life.

You have 66.52% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.