LETTER FROM ANTANANARIVO

As of Friday, February 23, Madagascar has become one of the world's most stringent countries in its approach to child rapists. In a ruling that cannot be appealed, the island country's High Constitutional Court (HCC) mandated the implementation of surgical castration for perpetrators of rape against minors. The court specified that this penalty must be applied "systematically" when the victim is under 10 years old, while its imposition for older victims will be left to the discretion of judges.

When tasked with assessing the legality of the bill passed by Parliament in early February, the magistrates exceeded the severity initially proposed by President Andry Rajoelina. The text submitted provided for the introduction into the penal code of a penalty of chemical or surgical castration. Prior to this, the penalty for raping a minor under the age of 15 was imprisonment, with a maximum sentence of life, albeit rarely imposed.

But the HCC deemed it contrary to the law's objective to retain the gradation of penalties according to the age of the victims. "Because chemical castration is temporary and reversible," it contradicts the aim of "permanently neutralizing sexual predators and reducing the risk of recidivism." Justice Minister Landy Randriamanantenasoa, who had justified the government's initiative by the need to combat the resurgence of rape, did not react to the HCC's decision.

The government's decision to focus on a penalty that is supposed to deter potential aggressors is far from enjoying unanimous support among victims' aid associations, who were not consulted on this revision of the penal code. "This response is not appropriate. It trivializes the stereotypical image of the isolated rapist, unable to control his sexual urges. But that's not the reality. In Madagascar, there is a culture of rape thriving within the confines of households, particularly among children and teenagers. This disconcerting phenomenon underscores prevailing power imbalances within relationships, ones that society tends to hush up in the pursuit of a dubious notion of cohesion within Madagascan social structures," lamented Marie-Christina Kolo, who founded the Women Break the Silence movement. "Victims, especially young children, often hesitate to report their aggressors, and families frequently opt for settlements involving financial compensation instead of pursuing legal action, as they lack trust in the judicial system."

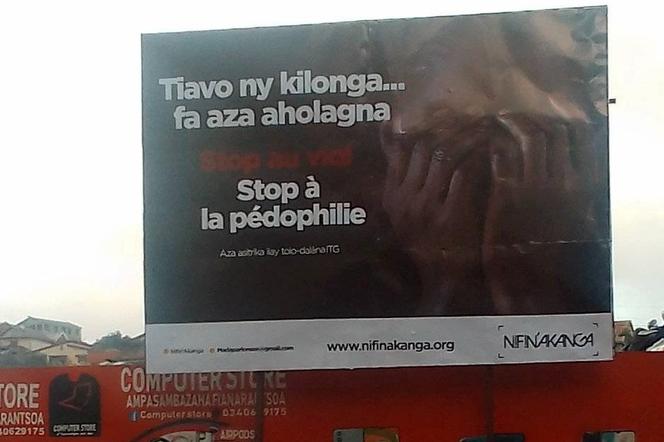

Like her, Mbolatiana Raveloarimisa, founder of the feminist association Nifin'Akanga, regrets that the government's plan fails to address protections for abused children: "Girls under 10 get pregnant and they don't have access to therapeutic pregnancy termination, which, regardless of the circumstances, remains forbidden in Madagascar."

You have 43.88% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.