The bloody attack on Moscow on Friday, March 22, which the Afghan branch of the Islamic State organization claimed responsibility for, reminds us of the terrorist threat that the influence of external conflicts can bring to bear on our soil. These conflicts – whether in the Sahel, the Middle East or Central Asia – serve as not only military but also ideological training grounds, and it's this combination that makes them particularly effective and dangerous. This phenomenon is not new. In a completely different historical context, it influenced the French Revolution; yet, in complete contrast to what is happening today, it enabled freedom and democracy to spread from the United States to France, according to a research paper entitled Revolutionary Contagion, authored by Saumitra Jha and Steven Wilkinson and published by Stanford University Graduate School of Business.

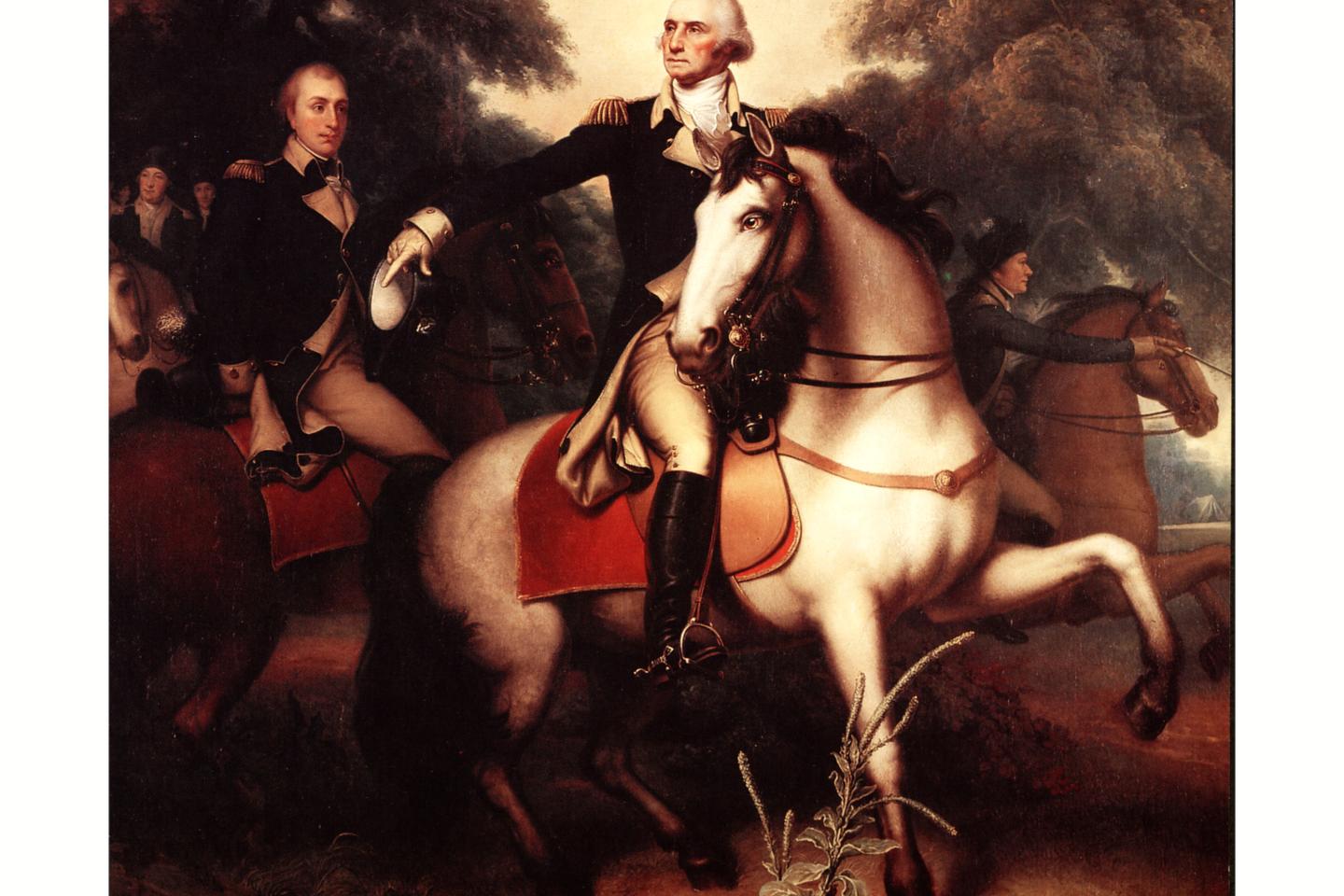

As Jha, an economist at Stanford, and Wilkinson, a University political scientist at Yale University, demonstrate in the study, the royal soldiers sent by French king Louis XVI to fight alongside the American revolutionaries against Great Britain from 1781-83 adopted the democratic cause, and afterward played a decisive political and military role in the French Revolution. In addition to the few French volunteers who were already committed to the cause of liberty and who therefore naturally became revolutionaries – Lafayette being the most emblematic representative of such – the February 6, 1778, Treaty of Alliance between France and the US called for regular troops to be dispatched, under the command of the Comte de Rochambeau. Of the 7,683 soldiers who were ready for departure from the port of the western French city of Brest in April 1780, only 5,028 actually embarked, due to bad weather and a shortage of ships. The soldiers who remained in port had been expected to join them as soon as possible, but the British naval blockade of Brest prevented them from doing so.

There was nothing that differentiated the troops who left to fight from those who remained in port, neither in terms of social and economic background, nor even – as the authors show by combing through the military records of over 51,000 soldiers – in terms of height, a criterion the researchers considered to be an indicator of the health and poverty of the soldiers as children. Yet the revolutionary destinies of these soldiers and that of the communities they came from (analyzed at the level of pre-Revolutionary administrative districts known as bailliages) were profoundly different.

You have 34.09% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.