Looking for the mysterious photographer who snapped occupied Paris and mocked the Nazis

Investigation'Photographer Unknown. Paris, 1940-1942' (Part 1/5). In 2020, Le Monde learned about the discovery of an album containing 377 photos of Paris during the Occupation by Nazi Germany. Who braved the occupiers' ban on outdoor photography to take these unapproved pictures? For four years, we investigated.

It all began quite simply, one morning in August 2020. On that day, at the flea market in Barjac, a town of 1,600 in southern France, a vintage photo enthusiast was browsing from stall to stall, looking for rare finds. Every year, Stéphanie Colaux visits the market to scavenge for albums like the ones they used to make, the ones bound in thick covers, containing black-and-white images with pretty scalloped edges. Weddings, birthdays, holidays at the seaside... these snapshots, rescued from oblivion, sometimes from the dumpster, exude the smell of attics and nostalgia, evoking distant intimacies and anonymous emotions. Colaux, co-founder of an audiovisual production company, enjoys imagining the stories and destinies behind each of them.

Strolling past one of the stands, she spotted a seemingly unremarkable album in a particularly poor condition. The laminated cover – very 1970s – showed two children playing with a model boat. Out of curiosity, Colaux decided to open it, and, to her astonishment, discovered a treasure trove.

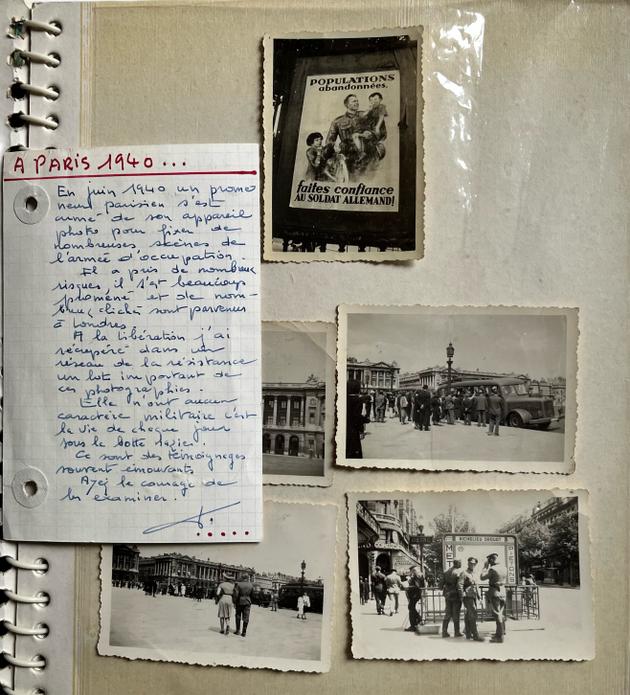

The pictures are of Paris, between June 1940 and March 1942, at the start of the Occupation of France by Nazi Germany. A time when taking photographs outdoors was prohibited, except for those accredited by the occupier. And yet, in this album, there are hundreds of them, 377 to be precise. Most of them are numbered and dated, offering a glimpse into the subjugated capital, gripped by a form of lethargy. The first photo, dated June 30, 1940, sets the tone by showing a propaganda poster, a drawing of a man in uniform with two toddlers, accompanied by a reassuring message: "Abandoned populations, trust the German soldier."

Short, punchy remarks

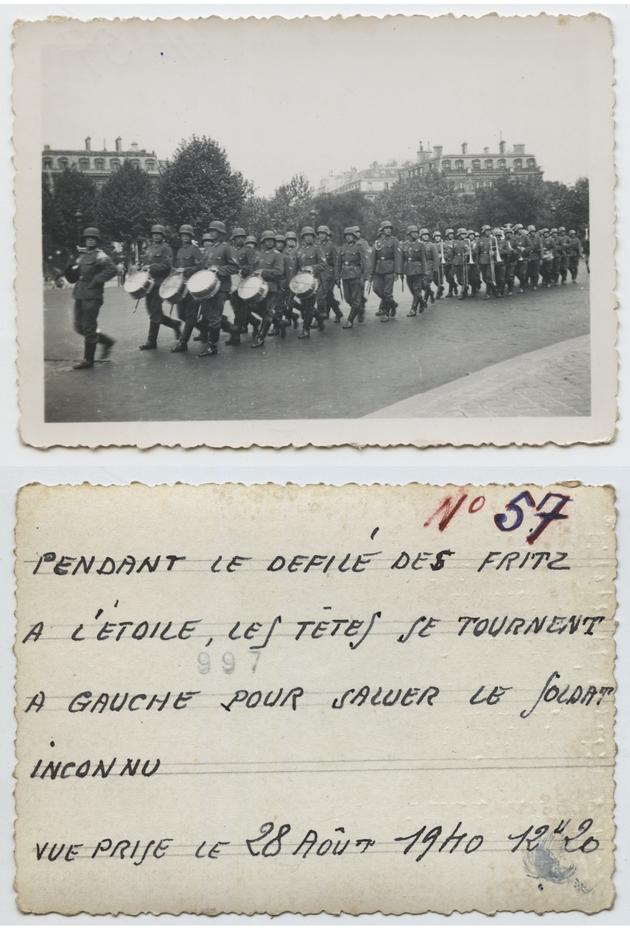

What follows is more of the same, with pages and pages of small-format images (8 × 6 centimeters) showing officers strolling on boulevards or the quays of the Seine in the company of young French women, others parading around the Arc de Triomphe or crowding the flea market. None of the people in the photos are posing; they are clearly unaware that they are being photographed. Some of the images have handwritten notes on the back, indicating the date, time and place of the shot, along with short, punchy remarks filled with a saucy, very Parisian sarcasm. All are written in capital letters, which would have been unusual at the time, making it seem the like author didn't want to be identified.

It's clear from reading these texts that the photographer had little love for the Germans – the "Fritzes" or "our protectors," as they are called. For example, Rue de Rivoli, June 30, 1940, 4:30 pm: "The German flag is flying, the street is deserted. Only our protectors are out and about."

In front of the Palais de Chaillot, August 4, 1940, 6:15 pm: "The Fritzes visit Paris while the French troops are doing winter sports in the Pyrénées."

At Saint-Cloud, on September 29, 1940, 3:20 pm: "Look at the friendly face of the gentleman on the left. Monsieur doesn't want to be photographed."

Place de la Nation, June 8, 1941, 4 pm: "At the Fête de la Nation, the Fritzes are astonished that the 'vanquished' are enjoying themselves while the 'victors' are bored..."

When Colaux asked to buy the album, the dealer hesitated, arguing that it wasn't really for sale, or that she'd have to pay a hefty price. He knew how fond collectors are of unearthing rare treasures, and this certainly was one. Colaux, being a well-informed bargain hunter, didn't give up. After some haggling, she walked away with the prize, aware that she had discovered an exceptional piece.

Photographs of occupied Paris do exist, of course, but most of the ones we usually see were taken by either German soldiers or French professionals with ties to the collaborationist press. The photos in this album have a very different, more natural tone. They document a moment in history, day by day, with commentary. The images and words were challenges to the occupier. And they were a mystery: At this stage, it was impossible to identify the photographer.

'Everyday life under the Nazi boot'

Colaux found another surprise on the first page of the album: a general note, a sort of introduction written by the person – also unidentified – who put together the album. The handwriting is clearly different from that of the notes on the backs of the photos.

This unknown hand wrote: "In June 1940, a Parisian stroller armed himself with his camera to capture many scenes of the occupying army. He took a lot of risks, walked around a lot, and many of the pictures reached London. At the Liberation, I recovered a large batch of these photographs from a Resistance network. They're not of a military nature, they're of everyday life under the Nazi boot. They are often moving testimonies. Have the courage to examine them." The message is signed only with indecipherable initials.

"Have the courage to examine them." Who was behind this intriguing message? And how could we find the photographer, this mysterious "Parisian stroller"? Colaux informed Le Monde of this baffling enigma, and so, in the fall of 2020, the investigation began. It would last four years.

The first thing to do, of course, was to consult historians to find out if they had ever heard of such a collection and if it might bear the mark of some network in the Resistance. On closer inspection, the chronology of the shots clearly narrows the field of possibilities. The first, as we said, is dated June 30, 1940; dozens of others followed throughout the summer of 1940. At the time, the ranks of the Resistance were very small in Paris. The capital was emptied of a large proportion of its inhabitants and reeling under the shock of the debacle. The June 18 call to resist issued from London by Charles de Gaulle, a general then unknown to the public, was little heeded.

The only active network, still in its infancy, was the "Musée de l'Homme" group. But according to the historian Julien Blanc, an expert of said group, the photos couldn't be linked to these "pioneers." Vladimir Trouplin, the curator of the Museum of the Order of Liberation, was also at a loss to say where they could have come from. As was Sylvie Zaidman, director of the Museum of the Liberation of Paris.

Another historian, Sébastien Albertelli, said that in the summer of 1940, the only rebellious acts were carried out by individuals. The images in the album, even if they passed at some stage through a network, appear to fit this description, suggesting that they were the work of a single person or a very small group.

A cartography of power

However, one thing is certain: The locations photographed in the first few months were not chosen at random. They bear witness to the stranglehold exerted on the capital by the occupying troops. If these images were placed end to end, they would form a kind of cartography of power. For example, numbers two and nine were photographed in front of the Ministry of the Navy, which was under German control. Number five was taken in front of the Hôtel de Crillon, a luxury hotel that became the headquarters of the military governor. Moving along the Rue de Rivoli, there's a photo of the Nazi flag on another luxury hotel, the Meurice, which was also commandeered. Additionally, there are photos in front of Notre Dame, on the banks of the Seine, at the Neuilly Bridge, and further west, in the metro stations of Sèvres, Saint-Cloud and Bécon.

The variety of locations is all the more astounding considering how the Germans tightened their grip as the fall of 1940 approached. A decree issued on September 16 forbade "photography in the open air, or from the back of an enclosure or from inside a house."

Only the occupying troops were not required to follow this rule, as well as a handful of French individuals, but a limited number and under controlled circumstances. The decree laid out a Draconian framework: "The competent Feld-Kommandant may dispense with this prohibition, when there is a guarantee that the interests of the Reich, in particular the security of German forces, cannot be compromised or harmed. Such a permit will be granted in writing and for a short period and must contain a list of the objects to be photographed. The authorized person must carry the permit with him or her. At the end of the approved term, the photographs (plates and film for prints) must be submitted for inspection to the local Kommandantur, to whom the permit will be handed over at the same time."

The Germans didn't have a monopoly on repression. From Vichy, the capital of the collaborationist French regime where the republican motto "Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité" (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity) had been replaced by the martial "Travail, Famille, Patrie" (Work, Family, Homeland), the government orchestrated a hunt for anyone who resisted the new order. In Paris and its suburbs, any act of rebellion became dangerous. By December 30, 1940, there had already been 842 arrests of people caught in the act and 411 administrative internments. The priority targets were communists and Jews.

Despite the risks, our unknown photographer didn't give up. At times, their journey resembles a logbook, providing a day-by-day account of current events. In late December 1940, they photographed the poster announcing the execution of 28-year-old engineer Jacques Bonsergent, the first French civilian to face the occupying forces' firing squad. The Paris Police Prefecture warned that tearing posters was considered an act of sabotage punishable by the "most severe" penalties. The photographer didn't care and continued to move from sign to sign. On the back of another photo, number 127, it is written: "It takes a lot of patience to find three intact posters."

Presence on sensitive sites

The photographer's favorite game was tracking Germans. It seemed like he was always there, observing them at a reasonable distance behind their backs, even when he watched tanks leaving for Germany at the Gare de Sèvres (number 121, October 27, 1940). The album includes one sequence after another, indicating that he spent entire days out and about, with a penchant for Sundays. The captions on the back – at this stage of the investigation, it was still impossible to determine whether they were written by the photographer or someone else – exude a caustic sense of humor. For example, on March 24, 1941, at 10:30 am, in the Tuileries garden: "After 10 months of Occupation, there are still Fritzes who don't know Paris." Or one summer Sunday when he caught an officer with a pair of young women: "Mr. Fritz on the boulevards, will he go to the hotel with the two chicks... Mystery?..."

None of the captions mention the photographer's name, not even a pseudonym. To identify the photographer, we figured that the best place to start might be by going back to the source, in other words, to the album's owner, another unknown who claimed, in the introductory note, to have recovered this "important batch" at the time of Liberation, "from a Resistance network." If the owner or their family members are still alive and available, they might be able to provide information about the "Parisian stroller" mentioned in the introductory note.

The album in question doesn't have a name or address. We initially tried to question the flea market seller in Barjac, but he was reluctant to give us any information. He suggested that the unusual object came from a house in the south of France that had been emptied after the death of its owner. Pressing the matter further would have been futile, as the world of secondhand sellers and collectors is secretive concerning the origins of their knick-knacks.

But there was still one hope, thanks to the old press clippings we found tucked between the pages of the album. These articles, taken from daily newspapers in the eastern Lorraine region, could help track down the owner of this antique object or someone close to him. One of the clippings mentioned a renowned member of the Resistance, Gilbert Grandval (1904-1981), head of the French Forces of the Interior in eastern France. Could this be the unknown person in the album, the writer of the introductory note? Attempts to verify the theory with his loved ones proved fruitless. Gandval, a war hero, a Companion of the Liberation and minister of labor, had no connection to our case. It seemed we would have to search elsewhere, delving back into the photos.

What do these photos tell us about their author? Historian Bénédicte Vergez-Chaignon, a specialist in the Occupation, examined the photos at the request of Le Monde and attempted to establish the photographer's profile. She began with a common-sense observation: If the time indications are accurate, how could he have moved so easily from one place to another, from the Jardin du Luxembourg to the Place de l'Etoile, from the Concorde to the near western suburbs (Saint-Cloud, Courbevoie...)? Did he ride a motorcycle in the almost deserted, heavily deprived Paris of early summer 1940? "That would mean he had access to fuel, which required vouchers issued by an authority," Vergez-Chaignon observed.

A far cry from propaganda images

Likewise, his frequent presence at various sensitive locations such as railway stations, command centers, and arms convoys is intriguing. "How does he manage to get so close to German parades and take photos?" asked the historian. "For a normal citizen, it's impossible."

The mention of a "stroller" in the note therefore seems hardly credible. Besides, there weren't many "strollers" – especially French ones – in Paris in the summer of 1940. The Germans' rapid victory had driven around two million out of three million residents, especially in the wealthier western districts, to leave the city. There were also very few cars, due to fuel shortages, and bus services had been discontinued, leaving the avenues virtually deserted.

The photos bear witness to a unique moment, showing us a paralyzed capital trapped in oppression. From the Invalides to the Madeleine, even bicycles are scarce. In front of the Saint-Lazare train station, we see baggage handlers slumped over on old-fashioned carts, waiting for hypothetical passengers (August 4, 1940, 2:30 pm). It would take a few more weeks for the Parisians who had left in the spring to return.

There's no doubt about it: These photos are light-years away from the propaganda images portraying an eternal Paris, happy and relieved, where Germans sit outside cafés. Our photographer preserved the truth: a captive, mute city.

At the time, miniature cameras – at least, small enough to hide under a coat and go unnoticed – already existed, as did easy-to-use shutter release devices. But to take and develop photos, you needed film, paper and a dark room. In those times of scarcity, everything was limited and controlled. "Unless you had a supply, or had some means, legal or otherwise, of obtaining one," pointed one Vergez-Chaignon.

Could a professional such as a photojournalist, with the approval of the Germans and the necessary equipment, have developed the photos? We proposed this hypothesis to another historian, Françoise Denoyelle, author of La Photographie d'Actualité et de Propagande sous le Régime de Vichy, ("News and Propaganda Photography under the Vichy Regime," 2003). She was also taken aback by this iconographic collection, which was developed on four brands of paper (Dinox, Velox, Ardex-Crumière, Gevaert). "It's magnificent, fantastic, truly extraordinary," she said. "But I can't imagine who could have taken these photos, and I've never heard of this story."

The photographer covers his tracks

In her expert opinion, the framing is good, worthy of a "pro," but the prints – on paper with scalloped edges, not "straight" – would suggest the work of a skilled amateur. In either case, Denoyelle also wondered how the photographer could have had such massive quantities of film and paper at their disposal. Furthermore, she found many puzzling mysteries: "How could he get so close to the Germans? And why take such risks? For some of the shots you're showing me, it was a guaranteed death penalty. Others, on the other hand, are of little interest. Why take them?"

Couldn't there be a detail in the album, however small, that would put us on the right track? We needed to classify these images, put them in order, and even display them on the wall like police working on an unsolvable cold case. We needed to try to find some coherence, some connection, some truth.

Little by little, the outline of a sketch emerged. The photographer was a man, seemingly, because he was referred to twice in the notes with the masculine "le photographe" rather than the feminine "la photographe." He was undoubtedly a Parisian, judging by his perfect knowledge of the neighborhoods. Whether he was a professional or not, he mastered the art of photography and had the necessary equipment.

There were other clues: He used a motorcycle or bicycle, and often stopped at "strategic" locations (stations, bridges, crossroads...). His preferred areas were western Paris (Opéra, Grands Boulevards, Champs-Elysées), where the Germans reigned supreme, and the present-day Hauts-de-Seine suburbs, from Sèvres to Courbevoie, an industrial sector rich in factories. On two occasions, in September 1940 and May 1941, he also visited Vernon, a town in Normandy partly devastated by bombing raids.

At this stage of the investigation, that was about all we knew about him. He had covered his tracks well. Whether they were written by his hand or not, the comments written on the backs of most of the photos only added to the mystery. Some were written very cleanly in black or red ink, while others had been scratched out and then rewritten, as if all or part of the original message had been removed with a letter opener. Why had some been redacted, and not others, containing only numbers (4, 35, 241, 419...) written in the same handwriting? We tried to access the erased messages by bringing in a specialist company, Photon Lines, with the type of equipment used on crime scenes. But the scratching was so deep that the texts remained unreadable.

The investigation continued online, in the hope of finding books or articles in France or elsewhere mentioning the name of a forgotten photographer. Search engines didn't have to dig far from Paris to suggest a lead: the Museum of the National Resistance (MRN), in Champigny-sur-Marne! It holds a collection of photos that are strangely similar to those in our album: same period, same format, same type of caption, with or without words scratched out. On the MRN's website, they are listed as coming from the "Daniel Leduc collection." Could this be our mysterious photographer?