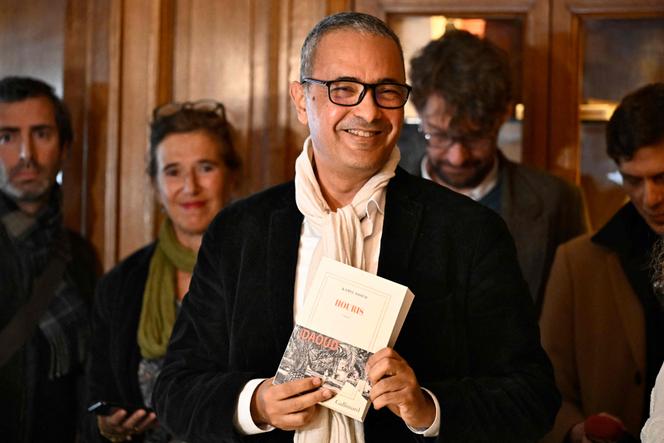

He had been declared the favorite for weeks, and on Monday, November 4, Kamel Daoud was awarded the Prix Goncourt for Houris (Gallimard, 416 p., €23, digital €15). This third novel, strikingly powerful in its dark, serious lyricism, gives voice to Aube, a young woman rendered mute by the botched slitting of her throat when she was five. It happened during the "black decade" of clashes between Islamist groups and the Algerian army (1992-2002). Aube speaks to Houri, the little girl she is carrying in her womb and is thinking of aborting, and sets off for the village where she was wounded, and where her parents, sister and a thousand other villagers were murdered.

I'm a child of Algeria, of the Algerian school, of Algerian ambitions. This prize has a lot of meaning, first of all, on a personal level (how can I escape it?): It's an achievement for me, for my family. It's also a strong signal for budding Algerian writers, those writers who are being terrorized by certain political currents, who are destroyed in the cradle and afraid to write. It's important for them to know that writing a book is a process that can have a happy ending.

As for context, I'm a writer, not a politician. A book encourages us to imagine, to hope for other things. A book can't change the world, but when it's widely read, it can become an instrument, a message. What I hope is that this book will make people in the West discover the price of freedom, particularly for women, and that it will make people in Algeria understand that we need to face up to our whole history, and that we don't need to fetishize one part of that history [the War of Independence] in relation to another [the civil war of the 1990s].

It's the readers who determine whether a book resonates or not. I'm a writer, columnist, journalist and Algerian (which is a profession in itself), and I hope people will open their eyes. I feel like I'm in much the same situation, all things considered, as the Soviet writers who warned of the gulag at a time when the praises of communism were being sung in the West. At some point, someone had to say that just because we hated imperialism didn't mean the gulag didn't exist.

You have 53.64% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.