In deserted Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan organizes an express tour of the reconquered enclave

FeatureThe Azerbaijani government exercises tight control over the former Armenian republic, which has been emptied of its inhabitants. In the Karabakh territories already taken over by its armed forces three years ago, all traces of Armenian presence have been erased.

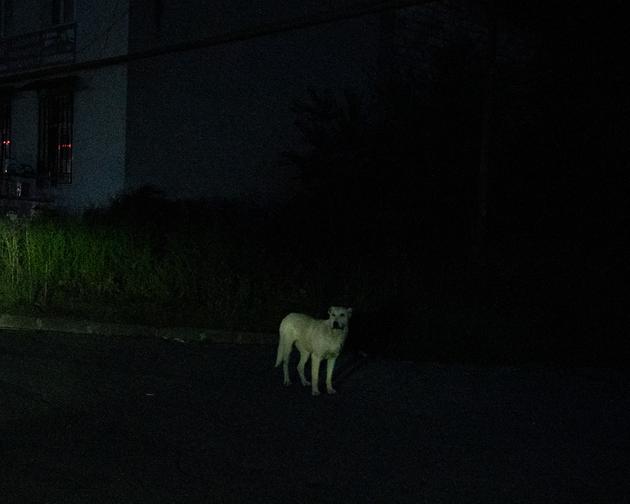

"First, the big ones will eat the little ones, then they'll eat each other, then they'll attack the humans. We'll have to kill them all," commented the driver as he sped through the deserted outskirts of Stepanakert (Khankendi, in Azerbaijani), the capital of Nagorno-Karabakh. Elnour recalled the packs of dogs roaming the streets of the towns and villages abandoned by the 100,000 or so Armenians who fled the former separatist enclave on September 26 and in the following days.

"We mustn't use that Bolshevik expression any more. From now on, we'll say 'territory formerly inhabited by Armenians'," commented Elnour, who was driving a handful of foreign journalists at breakneck speed on a visit organized by the Azerbaijani government from October 6 to 8. Dogs, three distraught little pigs and a horse covered in dust were the only living creatures to be seen in the vicinity of Khankendi, where 55,000 Armenians still lived before Baku's lightning attack on Nagorno-Karakabkh on September 19. No stops. The car sped off into the night towards Shusha (Shushi in Armenian), a town overlooking the entire Khankendi valley, already retaken in 2020 by Baku's forces at the end of the second Armenian-Azerbaijani war for control of the enclave.

It was impossible to find out more about what was happening in Khankendi, or in the rest of the "territory formerly inhabited by Armenians." Azerbaijan's presidential administration, which organized the press trip, favors areas that have already been recaptured over the past three years, and refuses to visit settlements recently deserted by the Armenian population. "It's for your own safety," said Baku's representative Elzar, claiming that snipers could be hiding in the buildings, and houses may have been booby-trapped or mined by Armenians in their hurried flight.

'Fifty Armenians' still there

Among the Azerbaijani soldiers we met, everyone had alternative and contradictory explanations, and agreed to speak only on condition of anonymity. "There are no snipers, but it's mined," one asserted. Another soldier said the opposite. A third assured us that two former Armenian separatist leaders on the run are being actively sought by the police, including Vitali Balassanian. He was one of the main commanders during the first Karabakh war (1991-1994) and then head of the National Security Council between 2016 and 2023, and is now the subject of torture charges. He is one of the most hated figures in Azerbaijan.

Two officers returning from Khankendi – without body armor or helmets – described a ghost town with streets littered with belongings abandoned by Armenians. "It's very quiet. The last Armenian officials and rescuers have left. There's an infirmary open, and an office for Armenians wishing to register with the authorities," one of them explained. "A few Armenian families have remained in Khankendi. There's a certain Gourguen, who I've become friends with. I'd take you to meet them, but you're not authorized." A UN mission, which has had access to Nagorno-Karabakh, concluded on October 2 that there may be "only 50 Armenians" left.

You have 56.84% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.