There is growing concern among African students following the adoption of the immigration law by parliament on Tuesday, December 19. The bill introduces stricter conditions for arriving and staying in France, and provides for an increase in tuition fees for foreign students, who will have to pay a "return guarantee" and will be subject to quotas. These measures are deemed "discriminatory" by unions and NGOs.

In 2020, France was the sixth-largest host country for foreign students globally, with 400,000 students. Morocco was the most represented country with nearly 46,000 nationals enrolled in a French higher education institution, followed by Algeria with 31,000 students. Around 15,000 Senegalese, 13,000 Tunisian and 10,000 Ivorian students were also enrolled in schools and universities in France.

"There's a migratory fantasy among the government and parliamentarians who voted for these measures. African students are suspected of cheating in order to be able to settle permanently in France," said Lina Hernandez, General Secretary of the Solidaires Étudiant-e-s student union. The law, which was passed the day after International Migrants Day, "establishes a discriminatory regime and a clear breach of equality between European and non-EU students," she added.

In addition to the "return guarantee," the text includes introduction of differentiated registration fees for foreign students. Higher registration fees had already been introduced in 2019 as part of the "Welcome to France" plan. However, this increase was rarely applied by university presidents, who largely took advantage of their right to exemption. According to Campus France, in 2023, 42 universities (i.e. 57%) fully exempted foreign students, and 16 universities (i.e. 22%) partially exempted students, according to linguistic, geographic or academic criteria. Only 13 universities (18%) have charged the higher fees in full.

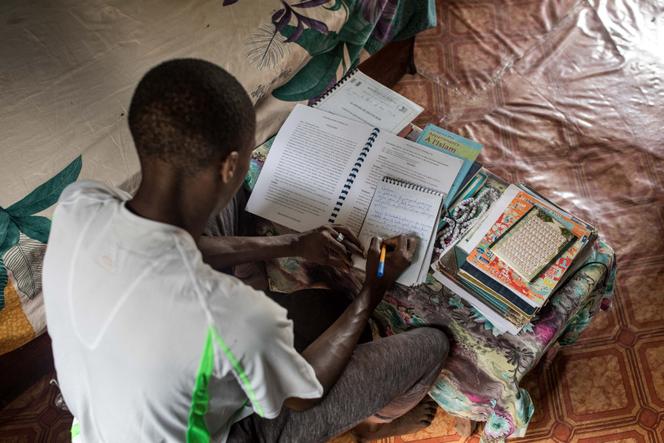

According to Salomé Hocquard, deputy delegate of the National Union of Students of France (UNEF), listing this in today's law means "generalization, with no possibility of exemption from the increase in tuition fees." The measure is seen as an injustice by Mohammed Lamine Diaby, 25, co-founder of the Student Federation for Africa and the Caribbean. Pursuing a double degree in philosophy at Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and a master's in management at EMLyon Business School, Diaby believes that "the law is targeting Africans" and "aims to give priority to American and Asian students." He calls the change an "ideological measure that has no financial justification."

The bill also establishes the principle of an annual parliamentary debate on immigration, as well as the adoption of immigrant "quotas." This debate will also cover student immigration, according to Olivier Marleix, president of the Les Républicains (right-wing, conservative) group in the Assemblée Nationale (lower house of French parliament). "This law is saying to African students: 'Don't come here, we don't want you', even though France remains a logical choice for students from French-speaking Africa due to history," said Congo-Ghanaian Uriel Asare, 22. Asare is pursuing an advanced university program at Skema Business School and is spokesperson for Voix des Étudiants Étrangers, an NGO that assists foreign students with administrative formalities, particularly the regularization of residence permits.

The bill also tackles criteria for applying for a long-stay visa, something already made more complex by digitalization. Under the current law, visa issue is conditional on the "real and serious nature of the studies," assessed "in the light of information provided by the training establishments and by the person concerned." The bill now requires students to provide annual proof of the "real and serious nature of their studies."

In fact, to obtain a long-stay visa marked "student," valid from 4 months to one year, you need to have at least €615 euros, or €7,380 per year, backed up by a bank certificate. "This sum in itself justifies the 'real and serious nature' of our efforts, especially when you see the sacrifices made by our families to send us to study in France," said Asare. "And then there are the tuition fees and living expenses."

Translation of an original article published in French on lemonde.fr; the publisher may only be liable for the French version.