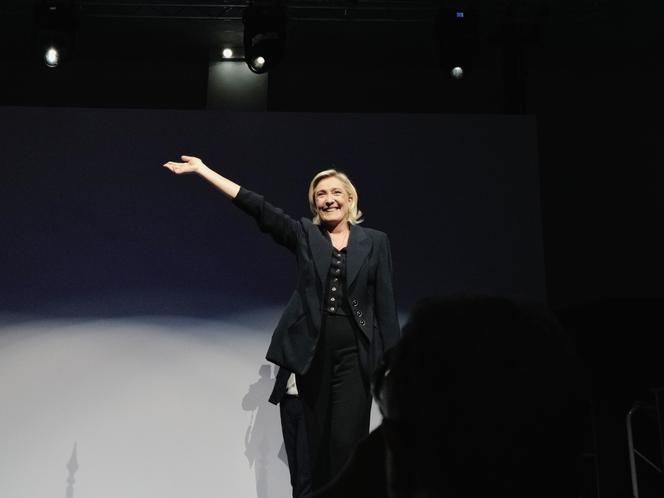

On April 24, 2022, on the evening of the second round of a presidential election that ended with more sadness than satisfaction at the 13 million votes she'd garnered, far-right Rassemblement National (RN) candidate Marine Le Pen called the re-elected president, Emmanuel Macron, and made him a promise: "If we take 3 million voters every five years, next time, it'll be us." Two years have passed since that boast, and the far right is knocking on the door of the prime minister's office.

At the time, the phrase sounded like a promise uttered without much belief. Le Pen wasn't thinking about 2027, not for herself. The presidential election runner-up spent her time holed up at home, far from the press and her supporters, while the left captured the headlines of the upcoming parliamentary elections. The far-right party, where nothing happens when the boss withdraws, accompanied her in this prolonged sleep until the parliamentary polls on June 12 and 19, 2022.

What did she have in mind for herself? Not much. President of an insignificant, marginal group in the Assemblée? "I was on the front line all the time, but I don't want to be," she told those close to her. The campaign was tough, disrupted by the media phenomenon of her far-right rival Eric Zemmour. On the evening of the first round, she worried about the rise in the vote for Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the leader of the radical left party La France Insoumise (LFI), who ended up just 400,000 votes behind her. Both men, in her opinion, played a role in the RN's favorable situation two years later.

On June 19, 2022, the RN's trajectory bounced back: the "republican front" was falling apart, and the far right won a majority of its duels against the left and Macron's camp. "The French have called me back!" Le Pen told her entourage, extending the electoral evening very late into the night, at the office of the mayor of Hénin-Beaumont, her friend Steeve Briois, where one phone call followed another from the RN's new MPs, some of them unknown to the president.

There were 89 of them, all potential mouthpieces for the party's xenophobic policies, unchanging on immigration but fluctuating on the rest. The party's finances, after years of struggling to make ends meet, would get out of the red. The RN parliamentary group, which was usually tiny and had little to offer, was attracting young radical right-wing graduates.

From time to time, an RN vice-president of the Assemblée sat in the president's chair, leading the debates respectfully, while the rest of the chamber hesitated on how to treat these tie-wearing, discreet, not overtly racist people who quoted Le Pen's policy platform like one believes in the Gospel. "We're not here for a long parliamentary career. We're here to conquer power," she told them during their first videoconference. "We're building a policy agenda and government teams at the same time." Two years later, few potential ministers have emerged, and the party still has no MP specializing in subjects as crucial as health or the environment. They are often quiet in committee sessions, where the technical nature of the debates seems to overwhelm most of them.

You have 72.11% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.