It took a long time to understand what the "Grand Paris" truly meant. For years, the term seemed to refer to little more than the Grand Paris Express: The huge transport network that will eventually restructure the area, with four lines due to serve 68 stations around the capital by 2030. The rest was vague, and with good reason: Since its creation in the early 2000s, the project's purpose has constantly changed. Originally conceived by officials from the Paris regional authority and the Paris City Hall, which were both under Socialist leadership at the time, it aimed to rebalance the region's economic activity for the benefit of the underprivileged eastern municipalities, and to commit the whole Paris region to the energy transition.

Former president Nicolas Sarkozy took it up again in 2007, once elected president. He wanted to use it as a means of attracting capital in the context of global competition between cities. However, it was under his successor, François Hollande, that the project took shape, with the creation of the Greater Paris Metropolis in 2016. Since its founding, the context has changed considerably, as geographer Anne Clerval and journalist Laura Wojcik have documented in Les Naufragés du Grand Paris Express ("The Castaways of the Grand Paris Express").

With the effects of the subprime crisis having been felt throughout the Paris region, public finances have been stretched to the breaking point; real estate started to become a speculative investment; the Parti Communiste gradually lost its strongholds to mayoral teams representing either the right wing or a faction of the left that has made peace with the market economy; and new administrative bodies, such as the Greater Paris Metropolis and territorial public establishments for intercommunal cooperation (EPCI), encouraged political maneuvering and hindered popular representation in the decision-making process.

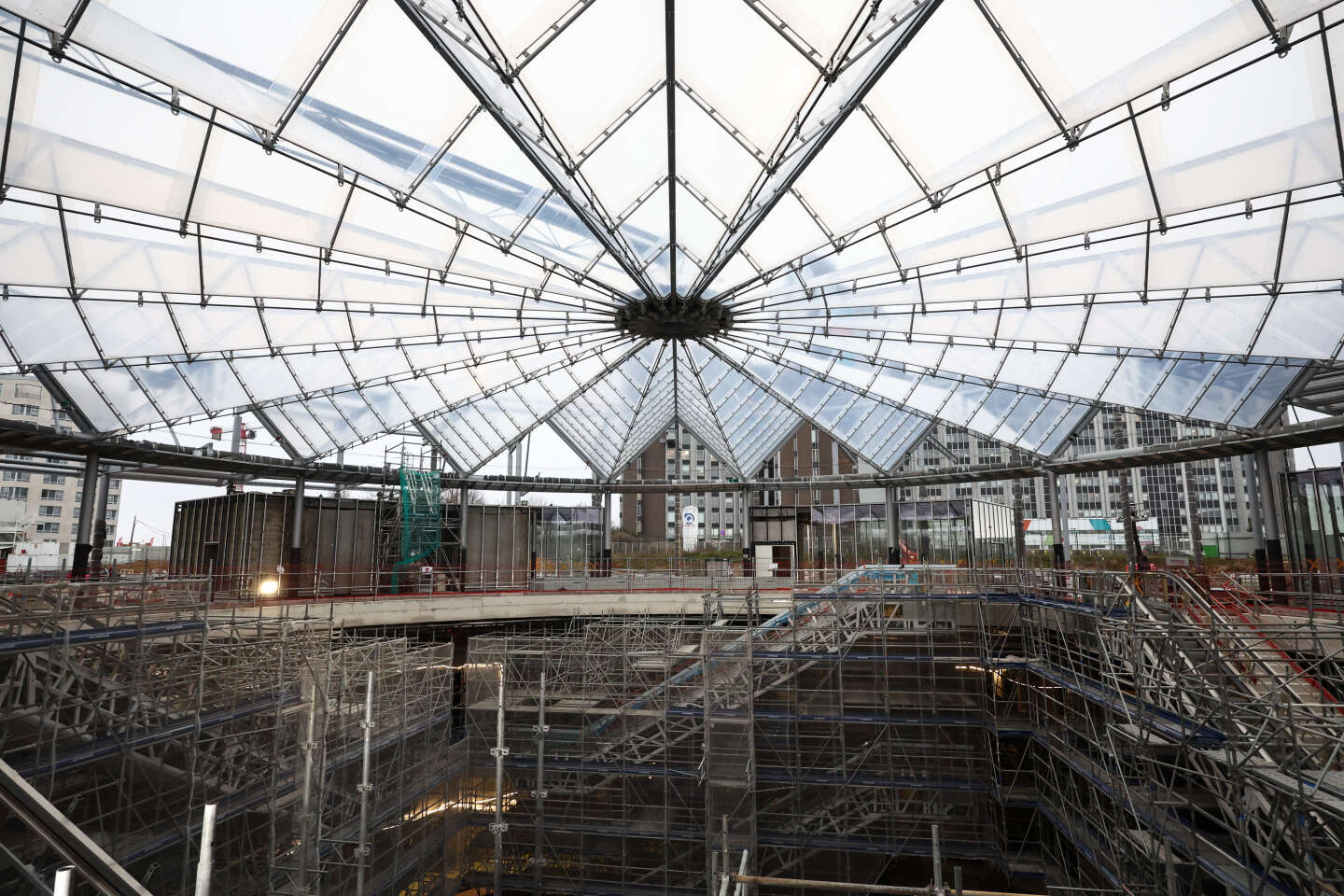

These factors have all contributed to making the Grand Paris into the hodgepodge it is gradually becoming: 182 "pieces of city" that have sprung up around public transport stations, according to the Paris Urbanism Agency (APUR), especially to the east of the capital, in the poorest suburbs. With property prices that were initially lower than elsewhere, the potential for development was greater.

Dismay and injustice

The construction of tens of thousands of mainly privately-owned housing units and the arrival of a new demographic with greater purchasing power than the local population will attract new businesses and economic activity, which will, in turn, lead to new real estate projects. The prospect of seeing these neighborhoods become directly connected to Paris and its suburbs has been fueling a process of gentrification the intensity of which is unprecedented in France.

You have 53.59% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.