From around 5,000 BC onwards, giant stones began to appear all over Europe, mainly in coastal regions. Examples include Carnac (department of Morbihan in northwestern France) and Stonehenge (Salisbury Plain, UK). This megalithic phenomenon lasted for almost four millennia. The Iberian Peninsula is no exception, with the impressive megalithic chamber of Menga near the Andalusian town of Antequera, where a Spanish team believes it has unlocked the secrets of construction in a study published Friday, August 23 in Science Advances.

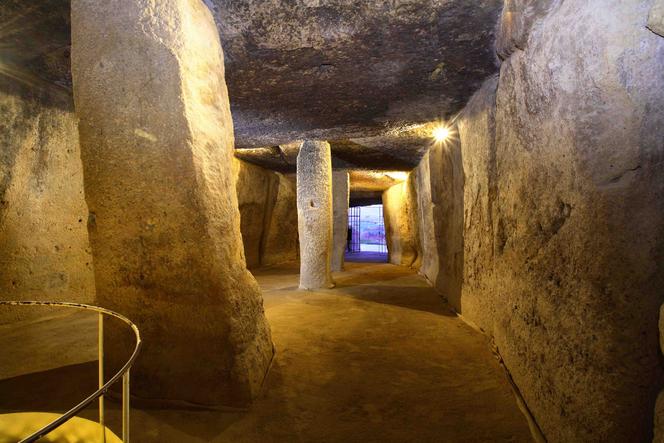

It was built around 3,800-3,600 BC, making it the oldest dolmen in Iberia. It is also the largest. Imagine a gallery 25 meters long, 6 metres wide and rising from 2.50 metres at the entrance to 3.45 meters at the bottom of the chamber. Each side of the chamber is made up of a dozen standing stones, joined together, on top of which are placed, by way of a roof, five enormous stones, the largest of which weighs 150 tonnes – the mass of a blue whale, the largest living animal on Earth. An original feature of the site is the presence of three pillars in the axis of the chamber, supporting these crowning blocks.

The total mass of this complex dolmen is estimated at 1,140 tons, which begs the legitimate question: How, almost six millennia ago, could a community have built this edifice? To answer this question, the Spanish researchers analyzed various sets of geoarchaeological data, in particular, the angle that each raised stone makes with the ground, the depth of the foundations, and also how each block fits in relation to its neighbors.

They were surprised to find that each of the two side walls was not perfectly vertical, but sloped inwards by around five degrees, giving the gallery a sort of ogival shape. In addition, the blocks are slightly beveled so that, once upright, each one rests on its neighbor. The result is better support for the upper stones, with some of the mass being discharged to the sides.

The authors have hypothesized that the blocks, cut in a quarry on the opposite side of the hill, were slid to the site on large sledges, where deep holes were dug in the ground. Here, the stones of the walls and pillars were slowly tilted using a system of counterweights, enabling them to be arranged with precision. Only their tops protruded from the ground. The coping stones were then slid on top. Finally, the earth was removed from the gallery to create the chamber.

"Dolmens have always had a funerary function," said the study's first author, José Antonio Lozano Rodriguez, from the Canary Islands Oceanographic Centre. But he remains cautious when asked how people were mobilized to build the Menga dolmen: "All we know is that Antequera must have been a gathering place some 6,000 years ago. This is how an aggregation of knowledge, and therefore of experience, was born in the context of an early but advanced science." For Lozano and his colleagues, far from being primitive, Neolithic humans deserved the title of engineers.